ENTENTE CORD

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By A. A. TOWNSIN, A.M.I.Iviech.E.

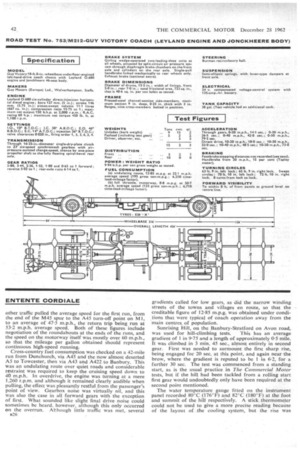

THE combination of chassis and bodywork produced in different countries is undoubtedly becoming more common, so that it was interesting to have the opportunity to road test a coach produced in this way. The Guy Victory underfioor-engined chassis has been well known on the export market for several years, whilst the Belgian Jonckheere concern has an international reputation for coach and bus bodywork. The characters of the chassis and body seemed mutually very well suited, and the complete coach was an impressive and very comfortable vehicle with a surprising turn of speed.

The Victory is available with the Gardner 6HLW or 6HLX or the Leyland 0.680 engine, synchromesh or direct-acting air-operated epicyclic gearbox and can be obtained with all-round air suspension, independent at the front, and disc brakes. The example tested had the Leyland 0.680.. engine, ZF six-speed synchromesh gearbox, orthodox semi-elliptic suspension and drum brakes. Michelin E20 "X " tyres were fitted all round in place of the standard 11.00-20 front and 10-00-20 rear tyre equipment. A road test report on a Victory chassis with Gardner 6HLW engine appeared in the June 20, 1958, issue of The Commercial Motor.

The coach tested was that exhibited on the Guy stand at the Commercial Motor Show in September. The operator for whom it was built, G. Meier Decloedt, of Ostend, sends coaches as far afield as Rome under the fleet name of Ostendia Cars. A high standard of comfort is obviously essential for a journey of this length, comparable to travelling from Glasgow to the Swiss frontier. By British standards the vehicle is decidedly heavy, the unladen weight of 9 tons 15 cwt. 2 qr. being at least 1.5 tons more than typical allBritish coaches of the same 11-metre overall length intended for Continental tours. Most of this extra weight is in the body, as the chassis weighs approximately 4.8 tons, a normal figure for a British model of this type. The standard of appointments • is perhaps marginally higher, with a toilet compartment at the rear and individually adjustable reclining seats, but the impression given was one of a very, solidly built vehicle on Which. nothing has been skiniped in the interest of weight saving. Creaks or rattles were conspicuous by their absence, and the :seats were .particulaxly comfortable.

The coach was loaded with sandbags .to give a gross laden weight equivalent to that with 46 passengers -with some 112 lb. of luggage each. Mr. R. E. Berry, public relations officer of Jaguar Cars Ltd., Gerry Mitchell, of Guy, and myself could be regarded as equivalent in weight to the two drivers and courier normally carried.

The test was commenced at the Jaguar works, mainly because of its proximity to MI, and the coach proved to be well suited to rinitorway. service. The initial impression given when moving-away from rest was of the engine having to work hard to accelerate the considerable gross Weight. This engine proved to be one that became • noticeably less noisy when wartned-up, but it could 'never besaidto he quiet when -accelerating 'and the -sound, •emitted had a harsher character than that associated with the similar but

smaller-bore 0.600 unit morefanailiarin this country. This initial impression Was greatly changed as the speed rose, however, and it steadily became apparent that the coach could eat up the miles in a remarkably effortless way.

The maximum speed on level road proved to be approximately 71 m.p.h., but on one Stretch. of the M45 motorway spur with a slight falling gradient it rose to 80 mph., at which speed there was no" impression of mechanical distress or excessive noise. The coach rode steadily, there was little wind roar and the overall. impression was of greater refinement than would be exPefienced in mbst private cars at that speed. On ordinary. Undulating main roads the performance was also very satisfactory, despite the moderate power/ weight ratio and high -overdrive gearing.

Contributing a great deal to this was the choice of gear ratiOs. As will already. haye heen gathered, the overdrive sixth speed, giving 31.7 m.p.h., per 1,000 engine r.p.tn., is almost ideal as a fast cruising gear, although acceleration is inevitably very leiSurely. An estimate of the maximum gradient that can theoretically be climbed at the steady speed in this ratio is 1 in 63, but much steeper short main road gradients could often be tackled without changing down if the initial speed was sufficiently high.

The direct fifth, giving .20.m.p.h.. per 1,000 engine r.p.m., represents a comparatively wide ratio step (1.59 to I) from

the overdrive. This limits. the -speed in this ratio to 49 m.p.h. and, as the governor begins to cut the power off at a little over 40 m.p.h., the practical limit for normal use is nearer the latter figure. There is, however, a useful increase in pulling power., which on paper becomes adequate for a 1 in 29 climb at a steady 22 m.p.h. and in practice remains usable at even lower speeds. As a result, this is quite a versatile ratio and the relatively good acceleration %time of 48-5 sec. for 10 to 40 m.p.h. with it in exclusive use, confirms the impression gained in normal service. None -the less, the lower ratios are inevitably frequently needed -Whenever steeper gradients or traffic delays are met and -the. speeds attainable in them are 8, 14, 21 and 32 m.p.h. respectively.

:.'_The motorway fuel consumption runs and, indeed, most of the test, were carried out in wet weather. Delays due to

ENTENTE CORDIALE other traffic pulled the average speed for the first run, from the end of the M45 spur to the A45 turn-off point on MI, to an average of 47.5 m.p.h., the return trip being run at 53-2 m.p.h. average speed. Both of these figures include negotiation of the roundabouts at the ends of the runs, and the speed on the motorway itself was mostly over 60 m.p.h., so that the mileage per gallon obtained should represent continuous high-speed running.

Cross-country fuel consumption was checked on a 42-mile run from Dunchurch, via A45 and the now almost deserted A5 to Towcester, then via A43 and A422 to Banbury. This was an undulating route over quiet roads and considerable restraint was required to keep the cruising speed down to 40 m.p.h. In overdrive, the engine was turning at a mere 1,260 r.p.m. and although it remained clearly audible when pulling, the effect was pleasantly restful from the passenger's point of view. Gearbox noise was virtually nil, and this was also the case in all forward gears with the exception of first. What sounded like slight final drive noise could sometimes be heard, however, although this only occurred on the overrun. Although little traffic was met, several

106 gradients called for low gears, as did the narrow winding streets of the towns and villages en route, so that the creditable figure of 12.85 m.p.g. was obtained under conditions that were typical of coach operation away from the main centres_ of population.

Sunrising Hill, on the Banbury-Stratford on Avon road,

was used for hill-climbing tests. This has an average gradient of 1 in 9.75 and a length of approximately 0.5 mile. It was climbed in 3 min. 45 sec., almost entirely in second gear. First was needed to surmount the first sharp rise, being engaged for 20 sec. at this point, and again near the brow, where the gradient is reputed to be 1 in 6.2, for a further 30 sec. The test was commenced from a standing start, as is the usual practice in The Commercial Motor tests, but if the hill had been tackled from a rolling start first gear would undoubtedly only have been required at the second point mentioned.

The water temperature gauge fitted on the instrument panel recorded 80°C (176°F) and 82'C (180'F) at the foot and summit of the hill respectively. A stick thermometer could not be used to give a more precise reading because of the layout of the cooling system, but the rise was ENTENTE CORDIALE

obviously no more than marginal. The ambient tempera ture was 4.4°C (40°F). An easy first-gear restart was subsequently made on the steepest gradient.

The weather conditions made complete brake testing virtually impossible. Several experimental full footbrake applications were made on wet surfaces, but front wheels, and, generally, the offside pair of rear wheels promptly locked, producing Tapley meter readings of around 50 per cent. The Guy testers had previously recorded figures of between 60 and 67 per cent on dry surfaces, and there seems no reason to disbelieve these, particularly as the brake system is similar to that of the Victory chassis tested by The Commercial Motor in 1958, for which particularly good figures were recorded. The system employs wedgeoperated shoes, and the only alteration made is a change in the wedge angle from 13° to 15° in the interests of extended periods between brake adjustment. This would theoretically slightly lower maximum retardation, but there is evidently a very adequate margin of safety. In normal use the brakes gave every confidence, with moderate pedal pressure and no more than slight delay effect caused by the direct air pressure system.

Resistance to Fade

Sunrising Hill was descended in neutral, using the brakes to maintain a steady 20 m.p.h., inan attempt to check their resistance to fading. Full application at the foot of the hill again locked all wheels except the neat-side rear ones in exactly the same way as had been done with the brakes cold, again with a 50 per cent Tapley reading. The road surface at this point was damp rather than wet, but had a greasy surface following foggy weather. Two-leadingshoe brake systems are often associated with high efficiency when cold at the expense of adverse fade -characteristics, but the degree of fade given by this example was evidently very mild. Further protection was given by the provision of an exhaust brake, with hand control.

The handbrake was the only section of the brake system that could be tested fully. The Tapley meter efficiency of 15 per cent could almost certainly have been improved had it not been for a somewhat unsatisfactory brake lever position. When fully applied the lever was too far back to permit the maximum pull to be developed by the driver's arm muscles.

Facing uphill on the 1 in 6-2 gradient, the handbrake would just hold the vehicle after it had been brought to rest using the footbrake. Releasing the handbrake slightly and reapplying it revealed that it was not, unaided, quite capable of stopping the vehicle when it was rolling backwards on this gradient. A total laden weight of 15 tons would be regarded by many engineers as about the practicable limit for a single-pull unassisted handbrake, but I feel that a useful improvement could be achieved by moving the lever forward slightly. A slightly increased leverage might also prove advantageous.

The standard of ride given by the orthodox suspension was very good in the laden condition as tested, particularly in the front. The degree of damping eliminated any-tendency to "float " when encountering a slightly uneven surface at high speed, but the ride never became jerky even when running over a very uneven temporary road surface at a more moderate speed. At the rear a:somewhat less level ride was given, but it was still much above average. Time did not allow an opportunity to sample the ride with the vehicle unladen.

A quite misleading impression would be given if the eight turns required to take the steering wheel from one lock to the other were taken as an indication of the amount of steering-wheel movement required in 'normal driving. The Burman recirculating-ball steering gear' has variableratio characteristics and is much " quicker " around the straight-ahead position than near full lock. The lock angles are good and the vehicle only just failed to comply with

the stringent 71-ft. swept turning-circle requirement which applies to vehicles of this type in Great Britain. The additional lock angle required could probably be obtained by simple adjustment and there is, in fact, no technical reason why a right-hand version of the Victory could not be operated in Britain.

Main-road handling characteristics were found to be very pleasant. The steering did not feel unduly low-geared yet it remained quite light and the degree of self-centring provided seemed just about right. A trace of road reaction could sometimes be felt through the wheel and a slight roll-steer effect was sometimes noticeable on country roads with adverse cambers, but the general impression was of precision.

The driving position was very good, with proper command over the wheel and pedals, whilst the range of forward vision given by the large windscreen was excellent. The positioning of some of the minor controls was found to be less satisfactory, however, a definite stretch forward being needed to reach the light switches and the flashing indicator control. It seemed as if the bodybuilders. had failed to appreciate the importance of grouping these within easy reach of the driver—by no means an uncommon

The least satisfactory feature of the coach, in my opinion, was the gear change. This was provided with compressedair assistance, so that light and quick-acting operation was to be expected. In practice, I found it more clumsy than an unassisted change-speed on a generally similar gearbox recently tested. If treated in a very leisurely way, the synchromesh was effective, but if a more rapid change was attempted it was by no means uncommon to find the gear refusing to engage, to the accompaniment of grating noises, until a second attempt was made, starting from neutral. The lever lacked "feel " and on several occasions 1 found that it had not been moved far enough to engage the gear required due to this, whilst finding neutral could sometimes be surprisingly troublesome.

The air assistance is controlled by a valve operated by the clutch linkage, not coming into operation until the pedal is almost' fully depressed. This is intended to prevent changing gear with a "live " clutch, but tends to add to the clumsiness of the gear changing procedure. The clutch itself is smooth in operation and not unduly heavy, however. To some degree, the difficulty I experienced with the gear change was undoubtedly due to my unfamiliarity with the technique for which it calls, but I noticed that Mitchell was also having trouble in making clean changes on a number of occasions. Guy Motors has improvements in hand, and one modification was already in effect on the test vehicle. Unintentional engagement of fifth or sixth gears when third or fourth were required was prevented by making a lifting movement of the gear lever necessary before the higher ratios could be selected. This was effective although it made the change from fourth to fifth rathei heavy.

Driving in the Dark Even with the present gearchange the vehicle is pleasant to drive, however. My stint at the wheel included a spell of driving on comparatively narrow roads in the dark and, despite the complications of left-hand steering and headlamp beams with a bias to the right when dipped, the coach gave no impression of being unmanageable. The quadruple headlamps had the main beams set slightly too high, but the dipped beams gave a good spread of tight with exceptionally even illumination, although they had to be used sparingly because of their unsuitability for driving on the left.

Time did not permit the usual maintenance tests, but rectification of a fuel-system air lock, caused when changing over to the test tank before the fuel consumption tests. confirmed that engine accessibility was rather better than on most underfloor-engined models, because of the high floor level—the provision of opening panels was thoroughly adequate.