Leyland Freightline Beaver

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

(semilulomalic)/Scommell

30-ton-glw. orlic BY A. J. P. WILDING, AMIMechE MIRTE

ERE is no doubt that the future for heavy truck transmissions

will be some form of automatic layout. This will be in line with the trend there has been for some time towards reducing the effort required on the part of the driver and it will also give improvements in maintenance, provided components are well designed.

Some people support fully-automatic transmission while others favour semi-automatic but after carrying out the first Press road test of a Leyland Beaver with the latter set-up, I would say that it would have to be a very good fully automatic unit to give an improvement. No work at all is involved in making ratio changes and a feature is that the driver can decide the moment when his experience tells him to make a change.

It is normal to pay in some other way for the sort of advantages that the semi-automatic transmission was found to Rive to the Beaver. But if there were any disadvantages I did not find them; nor could I see them. .Fuel consumption was better than that obtained on a test in 1965 of a similar outfit with a manual gearbox and there was a considerable improvement in acceleration times.

Progress along the road was much better and smoother as instantaneous ratio changes could be made and this was particularly useful when going up gradients where the effect was the same as if the engine had been given an extra 15 b.h.p. or so.

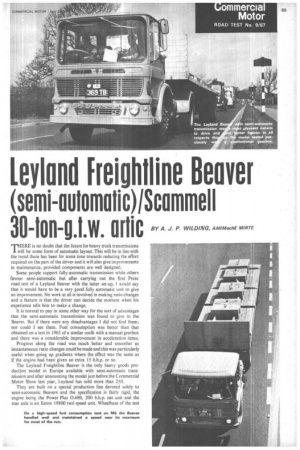

The Leyland Freightline Beaver is the only heavy Roods production model in Europe available with semi-automatic transmission and after announcing the model just before the Commercial Motor Show last year, Leyland has sold more than 250.

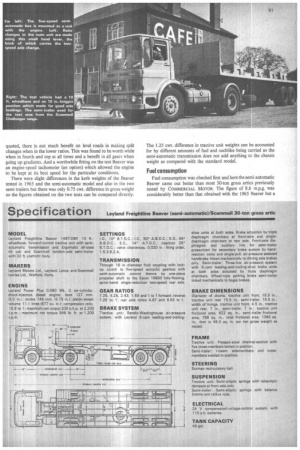

They are built on a special production line devoted solely to semi-automatic Beavers and the specification is fairly rigid, the engine being the Power-Plus 0.680, 200 b.h.p. net unit and the rear axle is an Eaton 19800 twO-speed unit. Wheelbase of the test

vehicle was 10 ft. and apart from this and the transmission and axle layout the tractive unit was the same as that on which a test report appeared in COMMERCIAL MOTOR of December 3,1965.

The Scammell semi-trailer used on this test had small differences dimensionally to the same make of trailer used in 1965 and had leaf-spring suspension instead of the Scammell stacked-rubber design. The model was from Scammell's latest Challenger range which has rolled-steel I-beam side members and the use of a Rubery Owen bogie results in a slight increase in brake size compared with the model previously tested; the diameters of the drums are increased by 1 in. which gives 9 sq. in. more frictional area.

To deal more fully with the major difference between the current outfit tested and the previous one—the transmission and rear axle—the gearbox is to the design of Self-Changing Gears Ltd., a subsidiary of Leyland. It is a five-speed unit similar to the box used in p.s.v. applications for many years consisting of a series of epicyclic gear trains and a multiple-plate clutch for direct drive. The box is mounted as a unit with the engine, the drive between the two being through a fluid clutch which is essentially a fluid coupling combined with a centrifugal lock-up clutch. The former deals with the requirements of smooth take-up from rest while the clutch ensures positive drive above a certain engine speed.

Forward ratios in the gearbox are 7.25, 4.28, 2.43, 1,59 and 1 to 1 with reverse 7.25 to 1 and coupled to a two-speed axle with ratios of 4.87 and 6.3 to 1, as in the test vehicle, this gives 10 distinct and progressive ratios throughout the range. A check of maximum speeds in the forward gears confirmed this. In first low the maximum speed was 6 m.p.h. and going through the box, splitting every change, the maximum speeds were 9, 11, 14, 20, 27, 29, 38, 45 and 60 m.p.h.

Selection of ratios in the main gearbox is through a small lever in a "gated" housing on the top of a column at the left-hand side of the driver. This sends an air-pressure signal to the gearbox to feed compressed air into the operating cylinder of the brake band of the appropriate epicyclic train.

Axle-ratio change The axle-ratio change is accomplished by moving a switch on the main-change knob and there are two safety features of the change mechanism worth mentioning. One is that the lever can be locked in neutral so that there can be no danger of a ratio being engaged when the vehicle is being worked on (this also can be used as a simple anti-theft device) and it is impossible to transfer the lever from the fifth-gear position to any gear except fourth, which prevents accidental selection of too-low a gear when changing down from top.

I have heard doubts expressed as to the feasibility of making ratio changes in a two-speed axle where there is continuous drive from the engine as with the Leyland semi-automatic gearbox. But while I would admit having had some difficulty initially and "losing" the axle on two occasions, there was never any serious problem and when the axle was "lost", drive was regained immediately and quite simply by changing the main ratio. Later on changing was simple and straightforward and the Leyland driver never had any trouble when he was handling the outfit.

Changing ratios in the main gearbox without changing the axle ratio at the same time is obviously perfectly easy; as soon as the lever is moved into the next position the ratio is selected. This can be done under full-torque conditions although this is not really advisable habitually as it can result in excessive brake-band wear.

When making axle-ratio changes only, the required ratio is preselected with full throttle applied and when changing up the accelerator is released until it is felt that the higher ratio has been engaged. Changing from high to low axle ratio is done in a similar way except that the accelerator is released momentarily and then pressed hard down to complete the change.

Simple operation Making main-gearbox changes and at the same time changing the axle ratio is even simpler and regardless of whether the change is up or down, the new axle ratio is preselected with full throttle applied and the change made by releasing the accelerator and at the same time moving the main change lever quickly into its new position.

As will be seen from the maximum speeds in the gears that were quoted, there is not much benefit on level roads in making split changes when in the lower ratios. This was found to be worth while when in fourth and top at all times and a benefit in all gears when going up gradients. And a worthwhile fitting on the test Beaver was an engine-speed tachometer (an option) which allowed the engine to be kept at its best speed for the particular conditions.

There were slight differences in the kerb weights of the Beaver tested in 1965 and the semi-automatic model and also in the two semi-trailers but there was only 0.75 cwt. difference in gross weight so the figures obtained on the two tests can be compared directly.

The 1.25 cwt. difference in tractive unit weights can be accounted for by different amounts of fuel and suchlike being carried as the semi-automatic transmission does not add anything to the chassis weight as compared with the standard model.

Fuel consumption Fuel consumption was checked first and here the semi-automatic Beaver came out better than most 30-ton gross attics previously tested by COMMERCIAL MOTOR. The figure of 8.6 m.p.g. was considerably better than that obtained with the 1965 Beaver but a lot of this was due to the fact that the rdute used before was particularly difficult for a maximum-length outfit being mainly over narrow and winding roads.

I estimated in the report that on a route more comparable to the usual type used by COMMERCIAL MOTOR a figure of over 8 m.p.g. should be obtained. This was confirmed on this test where a section of A6 north of Preston was used-an out-and-return run from just north of Broughton to the Mayfield Cafe, Garstang, measuring 16.4 mile. But more than this, the test showed that the Beaver is no less economical with automatic transmission.

High-speed consumption The high-speed fuel consumption tests were carried out on M6 by completing out-and-return trips between the Bamber Bridge junction and the B5329 turn off, a total distance of 19.2 miles. Here the semi-automatic model showed an improvement from 6.4 to 6.6 m.p.g. but more significant was the fact that the average speed was increased from 43.4 m.p.h. to 47.5 m.p.h.

The Beaver went extremely well on the motorway and the only change down necessary was to fifth-low when travelling south on the long gradient just before the Charnock Richard service area. Here the speed dropped to 37 m.p.h. but for the rest of the time the speedometer needle was resting mainly between the 55 and 66 marks (there was an inaccuracy of 5 per cent at maximum speed).

Acceleration times Acceleration times obtained with the semi-automatic transmission were considerably better than on the earlier test of the Beaver. The direct-drive figures cannot be compared because of differences in rear axle types and ratios but when going through the gears the time taken to reach 20 m.p.h. was reduced by 2 sec., 0-30 m.p.h. was 10 sec. less and 0-40 m.p.h. 17.6 sec. less.

Although there was no major difference between the braking system on the current test vehicle and the previous Beaver and there was only a slight increase in brake size of the semi-trailer improved brake figures were obtained; 4 ft. less was required to bring the outfit to a halt from 20 m.p.h. and the stopping distance was 5.6 ft. shorter from 30 m.p.h.

The improvements must have been due to changes made in valves and piping and more important in this connection is the fact that the secondary brake system was found to be much more effective. There was some improvement in efficiency-from 32 to 37 per cent-but a much more considerable improvement was evident in the way the secondary brakes operated. In the 1965 test report I criticized the design for the delay in the secondary system which amounted to more than 2 sec. On this test delay was not noticeable.

Changes made by Leyland have included the use of a relay valve in the secondary system for the supply to the semi-trailer auxiliary line. The feed to the semi-trailer brakes still travels from a tractive unit reservoir but previously the air used to go through the hand-control valve with an obvious restriction to the flow. Now only the front axle brakes are fed directly from the hand valve and only a small amount passes through this unit to send a signal to the relay valve for the semi-trailer. Taken all round the braking figures obtained with the Beaver were very good indeed and well up to the standard of other 30-ton attics tested.

Hill-climb performance Hill-climb performance checks were carried out on Parbold Hill as on the previous test. This hill is 0.75 mile long and has an average gradient of 1 in 12 with the maximum 1 in 6.5. The total time taken for the climb was 4 min. 55 sec. which was a little better than on the previous test and during the climb 43.5 see. was spent in first-high, the lowest ratio used. Minimum speed was 6 m.p.h. and in an ambient temperature of 13°C (55°F) there was no appreciable rise in engine coolant temperature on the climb.

Fade was checked by running down Parbold in top gear with the brakes applied to prevent the road speed exceeding 20 m.p.h. After a descent lasting 2 min. 21 sec. a Tapley meter reading of 55 per cent was obtained for a maximum-pressure brake stop from 20 m.p.h., only 6 per cent lower than the best figures obtained from both 20 and 30 m.p.h. on the earlier cold-drum tests. This indicated a negligible amount of fade and as on the main brake tests the forward-axle wheels of the semi-trailer locked for a short distance at the end of the stop.

The steepest section of Parbold was used for stop-and-restart tests. An easy restart was made in reverse high when facing down the slope and in first high when facing up and in both positions the handbrake held the outfit comfortably without air assistance.

I said in the test report of the first Beaver that I found it a most enjoyable vehicle to drive. From what I have already said it will be obvious that semi-automatic transmission adds to the pleasure. There have been sufficient favourable comments made in COMMERCIAL MOTOR road tests about the high standard of comfort afforded by the Leyland Ergomatic cab to make repetition here unnecessary. All that needs to be said is that the ease of gear changing matches the standard.

A longer wheelbase-10 ft. as against 8 ft. as on the earlier test machine made for an improved ride and with a farther-forward kingpin position, weight distribution over the tractive unit axles was improved. I was pleased to see that the front axle is now plated for 6 tons which allows some leeway in loading and the driving axle could have carried almost 5 cwt. more and still remained legal. But a point in this connection with axle weights is that with over 5 tons on the front axle the steering was a little on the heavy side and power-assistance may be a proposition.

List price of the semi-automatic Beaver as tested is £4,500 and the Scammell 32-ft. long tandem-axle semi-trailer has a basic price of £1,637.