Tailor-made troubleshooters

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IY HAVING a planned routine laintenance programme an perator is already halfway to laking the most of his vehicle. ind it is having the vehicles on le road for the maximum mount of time that makes the ioney.

The trade associations and ome of the oil companies roduce guidelines and sugested maintenance charts for perators and so do the vehicle lanufacturers.

It could be argued that the fac)ry which built the chassis in le first place is more likely to be ble to provide a detailed and ighly individual maintenance rag ramme.

Scania is one manufacturer rhich thinks along these lines, D I recently visited its service aining school where the comany runs courses on routine laintenance.

Each chassis manufacturer lows likely trouble spots and cania is no exception. Accordig to training officer Nick Leach we're realistic enough to know let all vehicles have problems Doner or later". So over the ears the manufacturers have evised their own maintenance thedules aimed at keeping their ehicles in top condition and lese are tailored to suit the degn of the particular chassis. Yes, it's possible for an expeenced fitter to be able to deal

with any vehicle, but the fact remains that it is impossible for a maintenance programme to be all things to all men.

The FTA, RHA and the oil companies all produce routine maintenance check lists for use by operators with a wide vehicle usage pattern but, excellent though these are as a base, they only go part of the way to providing a detailed maintenance programme for the individual make and model.

A classic example of the difference between an experienced mechanic capable of carrying out any job and one who follows a manufacturer's schedule is that of valve clearance adjustment.

This can be done using the long serving "rule of 13" but this involves a lot of engine rotating and is a nuisance for one man.

With the Scania design, the back of the cam is a pure semi circle, not a profile, and so this allows six valves to be set at one time.

With the D and DS8 engines, for example (as fitted in the 81), number one piston is set at tdc. When set at this position, six valves can be adjusted — namely number one (inlet), two (exhaust), four (inlet), six (exhaust), eight (inlet) and ten (exhaust). After setting this lot, the engine is turned over to tdc on number-six cylinder when the remaining valves can be set.

So although the old method would be enough in terms of providing the right valve adjustment, it would involve a lot more time and effort compared to applying this particular manufacturer's "wrinkle".

As with most of the competitors, Scania insists that valve adjustment is carried out on a cold engine. Not necessarily stone cold, as the vehicle has to be moved into the workshop in the first place, but the engine should be left to stand for at least a halfhour.

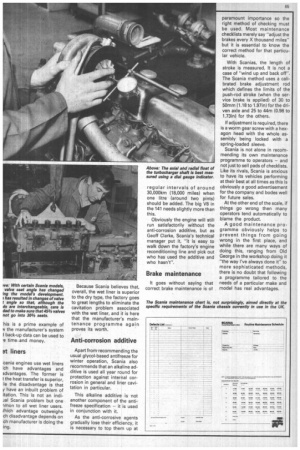

With certain Scania models, the recommended valve clearance has changed during the model's life as the continuous factory development programme comes up with im

provements. This has resulted in changes of valve seat angle, so care is needed to make sure that 45° valves don't go into 30. seats, for example.

While still on the subject of valves, Scania is one engine manufacturer who is set against the policy of lapping-in valves and seats. On Scania engines there is a difference of 1/20 between the angle of the seat and the angle of the valve (for example 291/2° and 30°).

This gives a knife-edge seal in most conditions but when the valve is closed and forcea against the seat by combustion pressure, then the valve bows and takes up this 1/20 difference.

Lapping, whether with coarse or fine paste, wears away this line contact and defeats the object of the design. So the manufacturer's recommendation in this case is to cut the seat, machine the valve, and just mate the two together.

It's a simple matter to check the effectiveness of the seal by pouring oil round the valve face and blowing compressed air into the port. Any leakage is then at once apparent.

Lubrication

Knowing how the engine is supposed to behave under specific circumstances is half the battle, and so it's essential to have access to the specification details. This is especially true with certain turbocharged engines which use oil spray nozzles to cool the underside of the pistons and this spray is taken off the main gallery.

In extreme circumstances, the oil light may come on under tickover (say 450rpm), but the criterion is that it should go out at 800rpm. This 800rpm oilpressure requirement is the minimum necessary for adequate lubrication and will probably be exceeded by most engines.

It has been known for a driver to report this "problem" so the oil and filters have been changed unnecessarily.

By the time this is finished the engine has cooled and the problem has ceased to exist. It is merely a question of knowing one's engine.

Included in the overall topic of "knowing one's engine" is knowing which oil to use. This doesn't mean make of oil but performance specification.

For example, Scania insists on a Series III oil for all turbcharged engines and as this is suitable for naturally aspirated units as well, it makes sense to standardise for a mixed fleet.

The reason for insisting on a Series III specification is because of the temperature requirement necessary for adequate lubrication of the turbocharger itself. A Series II oil will do for na engines, but it will carbon-up when going through a turbocharger.

According to Nick Leach, "lubrication is the key to good maintenance on a turbocharger".

Scania is one of the few engine manufacturers to incorporate a separate oil filter for the turbocharger lubrication circuit, and it is essential that the correct Scania part is fitted here as certain car oil filters have the same dimensions and method of location.

Although identical externally, the car filters have a lower setting for the by-pass valve and so must not be used.

With the high oil pressures of today's diesel engines, such filters would in effect be by-passed for 90 per cent of the time.

Turbocharger check

The turbocharger can be a good guide to the condition of the rest of the engine and the Scania maintenance programme makes use of the fact. Scania recommends an annual turbocharger pressure check where a pressure gauge is plumbed in to the inlet manifold. The vehicle is then driven in a gear which requires full engine speed and load. The pressure gauge is read at three or four different engine speeds.

Scania provides charts of turbocharger inlet pressure versus engine-speed and these can be used to verify that the engine in question is up to standard.

The graphs are based on an ambient temperature of 25°C (77°F), and so a correction factor is applied if the temperature is different to this. For example, a pressure reading of 0.5 bar (22psi) at 15°C (59°F) is corrected to 0.47 bar (21.6psi) at the datum of 25°C.

The pressure/engine speed readings are then plotted on the test graph. If the figures fall within the specified band, then the engine performance is sal factory.

Although this is mainly a t of the turbocharger pressu the last thing to do if the re ings are low is to change I turbocharger itself.

The reasons for incorrect t bocharger pressure are mz

and various and include: Cal blocked air filter;

(b) faulty injectors; (c) incorrect valve clearanc (d) leaking inlet or exha manifolds; (e) incorrect injection timi Note that of all these det which can cause incorr pressure, not one is directly at butable to the turbocharger self. )ve: With certain Scania models, valve seat angle has changed ling the model's development. ; has resulted in changes of valve t angle so that, although the ds are interchangeable, care is ded to make sure that 45% valves not go into 30% seats.

his is a prime example of fy the manufacturer's system back-up data can be used to 'e time and money.

e liners

icania engines use wet liners ich have advantages and advantages. The former is t the heat transfer is superior, lie the disadvantage is that y have an inbuilt problem of itation. This is not an indiJai Scania problem but one imon to all wet liner users. ihich advantage outweighs ch disadvantage depends on ch manufacturer is doing the ing. Because Scania believes that, overall, the wet liner is superior to the dry type, the factory goes to great lengths to eliminate the cavitation problem associated with the wet liner, and it is here that the manufacturer's maintenance programme again proves its worth.

Anti-corrosion additive

Apart from recommending the usual glycol-based antifreeze for winter operation, Scania also recommends that an alkaline additive is used all year round for protection against internal corrosion in general and liner cavitation in particular.

This alkaline additive is not another component of the antifreeze specification — it is used in conjunction with it.

As the anti-corrosive agents gradually lose their efficiency, it is necessary to top them up at regular intervals of around 30,000km (18,000 miles) when one litre (around two pints) should be added. The big V8 in the 141 needs slightly more than this.

Obviously the engine will still run satisfactorily without the anti-corrosion additive, but as Geoff Clarke, Scania's technical manager put it, "it is easy to walk down the factory's engine reconditioning line and pick out who has used the additive and who hasn't". paramount importance so the right method of checking must be used. Most maintenance checklists merely say "adjust the brakes every X thousand miles" but it is essential to know the correct method for that particular vehicle.

With Scanias, the length of stroke is measured. It is not a case of "wind up and back off". The Scania method uses a calibrated brake adjustment rod which defines the limits of the push-rod stroke (when the service brake is applied) of 30 to 50mm (1.18 to 1.97in) for the driven axle and 25 to 44m (0.98 to 1.73in) for the others.

If adjustment is required, there is a worm gear screw with a hexagon head with the whole assembly being locked with a spring-loaded sleeve.

Scania is not alone in recommending its own maintenance programme to operators — and not just to sell pads of checklists. Like its rivals, Scania is anxious to have its vehicles performing at their best at all times as this is obviously a good advertisement for the company and bodes well for future sales.

At the other end of the scale, if things go wrong then many operators tend automatically to blame the product.

A good maintenance programme obviously helps to prevent things from going wrong in the first place, and while there are many ways of doing this, ranging from Old George in the workshop doing it "the way I've always done it" to more sophisticated methods, there is no doubt that following a programme tailored to the needs of a particular make and model has real advantages.