HOW should one start a review of chassis at an

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

Page 88

Page 91

Page 92

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

exhibition of the importance that this year's Commercial Motor Show has turned out to be? There are the new heavyweight tractive units, the chassis with turbocharged and Perkins V8 engines, new p.s.v„ new six7 wheelers, trends to lightweight construction in four-wheelers and improved susperCsions and brakes.

Engines comprise the large part of the Earls Court story this year, particularly with the advanced Leyland fixed-head 500 diesel and Ford turbocharged diesel. But even these and the major introductions by most of the British Leyland Group are overshadowed by the announcement, just before the Show opening day, of the British Leyland 400 bhp gas turbine and the truck that goes with it.

Although current models are an operator's bread and butter—and some of the latest show signs that there may be some jam as well—it is most significant that BLMC is forecasting the gas turbine as a viable proposition in respect of both manufacture and operation within the next five years.

Potential outputs of the new AEC V8 and the Leyland 500 approach that of the gas turbine and this forecast by BLMC confirms my view that the two power units mark the final stage of development of high-output vehicle diesels by the concern. A lot of operators look with disapproval on the trend to increased power. And with justification when advantage cannot be taken of the improved productivity. But with more advanced techniques of vehicle operation there will be the need for power/weight ratios of the order of 8 or more bhp per ton even if legislation were not to be introduced eventually to demand this.

With a 38-ton or 40-ton gross weight for artics maximum engine outputs of around 300/350 bhp will be needed. There must come a time when the longest and heaviest artics will be restricted to specific routes, and it is more than likely that these will be used for long trunk routes with a split-up of the loads at the outskirts of cities for local distribution by lighter and therefore lesspowerful vehicles, using trailers such as the York 2/20 seen in the trailer section.

It is against a probable future background of two-stage haulage such as this that the Leyland gas turbine tractive unit must be considered. It is on this sort of long-distance running at high speeds with high gross weights that the turbine will achieve equality with higher-output diesels in running costs.

Leyland Gas Turbines has done numerous tests and evaluations on the subject and the results indicate that fuel consumption will be less than 3 per cent worse on a 400 bhp turbine than on a comparable diesel, with counter-balancing advantages for the turbine of extra life between overhauls and lower weight among other things.

With 6 or 7 mpg a general return on tests of 32-ton gross artics with 200/250 bhp diesels, it is obvious that consumption to be expected at around 40 tons will not be much over 4/5 mpg. But at the same time the gross weight, the higher average speed possible and reduced driver strain through having higher power, have to be taken into consideration.

We must also consider the concept on an international-transport basis. Britain is becoming less of an island for road transport and when there is eventually an integrated Europe with a full motorway network, vehicles like the Leyland gas turbine will be essential.

Government actions seem likely to delay

things but can they support dying railways forever? Maybe a government will say one day, "Do we really need a railway system?" and it may find the answer is "Not" Then we can positively develop road transport.

With an advanced road system well in hand already, America has been able to speculate with more certainty on the future uses of gas turbine vehicles. One of the results is to be seen in the shape of an American Ford unit on the Ford stand. This has been in a truck for a longer time than Leyland's but it is not necessarily more advanced. The two turbines are to a similar design but British Leyland's Gas Turbine Division was formed from the Rover Group which had had the high output unit as a design project for many years. Rover had also done a lot of pioneering work on the ceramic regenerators—used also by American Ford—which provide for the extra fuel economy required to get a consumption comparable with that of a diesel of the same output.

One important aspect of the Leyland gas turbine truck is the thought that has been put in other directions to make the chassis and cab match the power unit. Improved ride can be expected from the use of taperleaf springs at the front axle; fully automatic transmission will make the driver's job easier and although the rear bogie and suspension are basically the same as on the new Leyland Bison, the Ergomatic-based cab has been completely changed.

Externally the unit is very attractive and internally furniture and fittings are in many respects in advance of what can be found in the most expensive motor car. One wonders how much of the high standard could be retained for a production job but this indicates the right thinking for the future.

Extended road tests carried out by Commercial Motor have shown that approaching 400 miles is quite possible in 11 hours driving in some of our current maximum gross artics even when this dis tance includes a fair proportion of con gested and poor roads. But I have found that a high interior noise level and inferior seating and suspension cause a considerable amount of additional fatigue, and would be surprised to find any driver capable of doing such daily journeys on a regular basis in this type of machine.

In the case of a vehicle such as the Leyland gas turbine, this sort of daily journey could be considered as a routine task; one of the big advantages of the turbine is its inherent quietness which was illustrated clearly when the vehicle was driven at its unveiling.

If there is one thing that heavy-vehicle operators can be thankful for at this Show it is that British manufacturers appear to have

caught up with the changes in operation that have taken place in the past few years—

heavier weight, more intensive use of vehicles and so on. Engines have had to be "stretched" by increasing governed speed and capacity to meet new power require ments and this has often resulted in afar from ideal reliability situation. With engines such as the AEC V8 and Leyland 500 designed for far higher powers than on their initial use, reliability should be inherently good.

It is interesting that these two major members of British Leyland should have introduced in the same fear engines so completely different. The AEC is an oversquare design—bore is greater than the stroke dimension. It is in line with the trend that there has been towards this layout of power unit, giving as it does a more compact unit and incidentally allowing a big improvement in the cab interior layout. The Leyland on the other hand has a conventional bore and stroke relationship and departs from convention completely by having the block and head cast as one component. With this arrangement operators may recall problems with loosening of block holding-down bolts on older engines having separate block and crankcase, but it is to be hoped that improved techniques have overcome this potential problem and in any case we should wait and see.

An important feature of the 500 is its versatility, not only in respect of increasedpower potential—up to 260 bhp when turbocharged is a probability within the next 12 months—but also in the way the accessories have been designed to allow the engine to be used for numerous applications.

AEC introduced the V8 first of all for the Mandator 32-ton-gross tractive unit and at this Show is applying it to the V8 Mammoth Major six-wheeler tractive unit for maximum-gross weights allowed on the Continent—and possible in this country before long—and also in a high performance ,p.s.v. called the Sabre. This latter chassis should be well received in most European countries to meet demands for high-speed luxury-touring coaches.

The Leyland 500 has its first application in the new Lynx and Bison, fourand six-wheelers respectively for maximum British legal gross weights. Both these chassis have many interesting features including the use of high-tensile steel frames which keep weight down, a re-styled cab which retains most of the features of the original Ergomatic unit and new gearboxes including a 10-speed range-change unit in the 28-ton-gross Lynx tractive unit. With estimated chassis/cab weights of about 4.75 tons for the Lynx and about 6 tons for the Bison 6 x 4, the new models offer favourable payload allowances and the Bison looks particularly good as a basis for tipper bodywork. A concern has been expressed in the past about the reduced competition in the commercial vehicle industry with the amalgamation of the Leyland Motor Coporation and the British Motor Corporation. The spread of the resulting British Leyland Motor Corporation is illustrated at the Show by the fact that 11 of the 24 British manufacturers exhibiting are in the Corporation, but the impression one gets is that the competition has increased if anything and each one is vying at Earls Court for the limelight.

Every one of the 11 members has a new chassis and as well as those on the Leyland and AEC stands, Scammell is featuring a new model designed for the future. This is the Crusader, a 6 x 4 tractive unit for gross weights of 40 tons and above and while the standard power unit is a Cummins 320 bhp V8, the Show exhibit has the optional General Motors 290 bhp V8 two-stroke diesel. Both have Fuller RTO 915 15-speed gearboxes and the specification looks to be aimed particularly at export markets. But the chassis is also built with the future possible increases in British artic weight limits in mind and the AEC V8 and transmission are also to be offered. This would be a logical step for the British market because of the considerable reduction in price that would result.

Also aimed at export is the revised Big J 6 x 4 truck shown by Guy. This machine has a sleeper cab and is rated for use at 26-tons-gross solo or 45 tons with a drawbar trailer. Various improvements have been made to the original design of this Big J six-wheeler including the use of a different arrangement for the location of the trunnion brackets for the two-spring rear suspension. The bogie has a capacity of 20 tons with the front able to carry 7 tons and a feature is a fully flitched chassis frame. A new design of sleeper cab is fitted and the interior is to the high standard which is demanded on the Continent and in the past four or five years more usual on vehicles for Britain, too.

The new Albion exhibits are quite different in that they are primarily intended for home consumption. In keeping to its niche in the BLMC producing low-price, low-cost trucks with reliable and simple specifications Albion has introduced the Reiver 129 6 x 4 for truck mixer use. For operators who do not want fancy trim for this type of on-off road vehicle, the old Panoramic cab is retained but there is more power than normal for Albion with the use of the AEC 505, 151 bhp diesel. The gearbox is the new AEC-designed 10-speed range-change unit made by Thornycroft and used in the new Leyland Lynx tractive unit.

There is only a slight change in specification for the second 6 x 4 shown by Albion. This is the Super Reiver 20 with the higherstandard Ergomatic cab and Leyland 401. 138 bhp engine. And this chassis has the latest Albion 10-speed splitter gearbox which now incorporates synchromesh for the lower of the splitter ratios and an improved control system for this section of the box.

Anyone who has been saddened by the fact that BMC has not been as successful as it should have been with the FJ design will be pleased to see the introduction of the Laird range which incorporates all the improved-reliability features built into the FJ in recent times. As well as a re-styled cab front and better seating, the Laird has a straightforward hydraulic clutch among other modifications.

BMC also has its new EA 30-cwt van at the Show, of course, and both these models should give a good account of themselves. In the past there was an impression that the truck division was the under-privileged child of the BMC family. But this has changed, and now at BMC the whole of truck design and—of more importance—truck development and proving has been completely revitalized and put on a very strong foundation.

In the whole of Europe, except Sweden and Holland, operators are reported to be distrustful of turbocharged diesels. But the lead given by makers in these countries has shown that a turbocharged engine can be as reliable as a naturally aspirated diesel and give some advantages, too. There are certainly signs that attitudes in general are changing. Leyland has sold trucks with its turbocharged 680 engine overseas and is featuring such a model at Earls Court. And now Ford is the first British maker to standardize on a turbocharged engine for a goods model—the DT1400 range. Ford has also introduced the turbocharged 360 cu.in. engine as an option in a number of D Series chassis as well as in the R Series p.s.v. chassis which have a number of other changes as well.

A degree of design sophistication not common on heavy commercial vehicles is evident from the Scania-Vabis and Volvo vehicles which are being displayed at Earls Court for the first time. These two marques have done reasonably well in the short time that they have been available to British operators and while the models on both stands have a number of basic similarities such as turbocharged high-output diesels, tilt cabs and so on, there is one aspect in which the basic designs are completely different—Scania uses a splitter gearbox while Volvo uses range-change units.

This is mirrored in the two latest Albion six-wheelers I have already referred to and it is interesting to consider the arguments put forward in favour of each type. In the first place, use of splitter gearing to double the number of main ratios in the gearbox started off largely as an expedient to save a completely new gearbox having to be designed. It is not always possible to get ideal steps between the increased numbers of ratios but this is the main advantage of the range-change unit. As all the gears in the main section of this type are used with low auxiliary ratio and then with high, it is possible to select ideal ratios for the higher intermediate gears.

It is likely because of this that completely new boxes in the future will be of the rangechange type as is the case with the new Thornycroft-built BLMC unit. But there is a disadvantage from a driving angle in that every change is a manual one; with a splitter box the low or high ratio in each gear is usually an easy change by moving a small lever and depressing the clutch. There are road conditions where not every ratio in a box is needed, and with range-change it is more awkward to jump ratios than omitting split changes in the other type of unit. Also, it is easy to forget exactly which gear is engaged with a range-change box until a driver has got used to it.

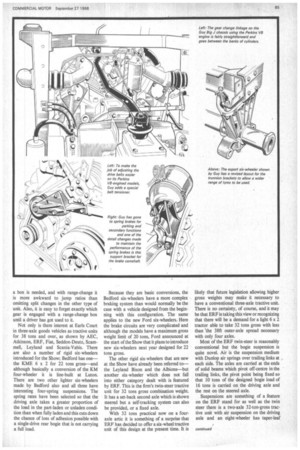

Not only is there interest at Earls Court in three-axle goods vehicles as tractive units for 38 tons and over, as shown by AEC, Atkinson, ERF, Fiat, Seddon-Deutz, Scammell, Leyland and Scania-Vabis. There are also a number of rigid six-wheelers introduced for the Show; Bedford has one— the KME 6 x 2 for 22 tons gross—and although basically a conversion of the KM four-wheeler it is line-built at Luton. There are two other lighter six-wheelers made by Bedford also and all three have interesting four-spring suspensions. The spring rates have been selected so that the driving axle takes a greater proportion of the load in the part-laden or unladen condition than when fully laden and this cuts down the chance of loss of adhesion possible with a single-drive rear bogie that is not carrying a full load. Because they are basic conversions, the Bedford six-wheelers have a more complex braking system than would normally be the case with a vehicle designed from the beginning with this configuration. The same applies to the new Ford six-wheelers. Here the brake circuits are very complicated and although the models have a maximum gross weight limit of 20 tons, Ford announced at the start of the Show that it plans to introduce new six-wheelers next year designed for 22 tons gross.

The other rigid six-wheelers that are new at the Show have already been referred to— the Leyland Bison and the Albions—but another six-wheeler which does not fall into either category dealt with is featured by ERF. This is the firm's twin-steer tractive unit for 32 tons gross combination weight. It has a set-back second axle which is shown steered but a self-tracking system can also be provided, or a fixed axle.

With 32 tons practical now on a fouraxle artic it is something of a surprise that ERF has decided to offer a six-wheel tractive unit of this design at the present time. It is likely that future legislation allowing higher gross weights may make it necessary to have a conventional three-axle tractive unit. There is no certainty, of course, and it may be that ERF is taking this view or recognizing that there will be a demand for a light 6 x 2 tractor able to take 32 tons gross with less than the 38ft outer-axle spread necessary with only four axles.

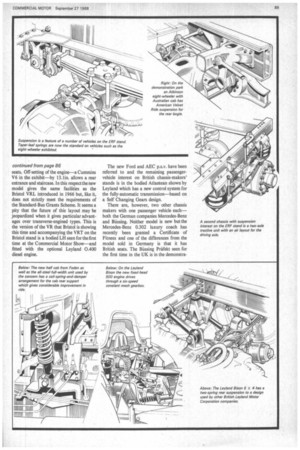

Most of the ERF twin-steer is reasonably conventional but the bogie suspension is quite novel. Air is the suspension medium with Dunlop air springs over trailing links at each side. The axles are carried at the ends of solid beams which pivot off-centre in the trailing links, the pivot point being fixed so that 10 tons of the designed bogie load of 16 tons is carried on the driving axle and the rest on the steered axle.

Suspensions are something of a feature on the ERF stand for as well as the twin steer there is a two-axle 32-ton-gross tractive unit with air suspension on the driving axle and an eight-wheeler has taper-leaf springs for the rear four-leaf-spring suspension layout.

This is now the ERF standard for eightwheelers and it is worth noting here that in spite of many views to the contrary the eightwheeler is far from dead. .Atkinson has an eight-wheeler on the demonstration park— with suspension also a feature, as it has the Velvet Ride system now marketed in the UK by Holset. Guy and Foden are two other exhibitors of eight-wheelers and on the Scammell stand there is the new version of the Routeman with double-drive rear bogie. This double-drive really explains the interest in this type of chassis, as all are for 24 tons gross tipper use primarily.

With the prospect of the Transport Bill making operation of over-16-ton vehicles difficult, manufacturers are showing more interest in maximum-gross four-wheelers. With the challenge that developed when the quantity producers entered this market at the 1964 and 1966 Commercial Motor Shows, the traditionally heavy manufacturers seemed to grow rather cool and to concentrate on heavier attics. Leyland shows that it is taking up the challenge with the Lynx, and ERF is showing a new four-wheeler which, like a new Guy Big J with Leyland 401 engine, is designed for lightness.

A plastics cab similar in appearance to that used by ERF on its fire-appliance chassis is employed and this gives forward entrance; high-quality interior fittings are used. The chassis has a Gardner 5 LW 94 bhp engine driving through an Eaton 542 SMA gearbox. The rear axle is a lighter but stronger design than similar units previously used by ERF and in order to keep the weight to a minimum Stopmaster brakes which have actuators at each end of each shoe are used. Unladen weight of the chassis cab in production form will be less than 4.5 tons.

The major exhibit on the Dennis stand is the new front-wheel drive ambulance which is dealt with elsewhere in this issue and was described in detail in Commercial Motor of September 13. This is very important to municipal readers but goods vehicle operators visiting the Dennis stand will be more concerned with the Pax V 15-ton-gross four-wheeler introduced last year which is also designed for lightness. Dennis is marketing the vehicle on its payload capacity which is not far short of what can be expected on a normal 16-ton-gross fourwheeler and with a specially designed 26ft long light-alloy body which weighs just. over 12cwt, the kerb weight of the complete vehicle shown is 4.35 tons.

I dealt with new engines at the beginning of this review, but an existing power unit which has leapt into very widespread popularity at this Show is the Perkins V8.510 which produces 170 bhp in British gross terms and 185 bhp when rated to the American SAE gross standard. This engine has been adopted by Ford, Dodge, Guy and Universal Power Drives for their latest goods vehicles and is an option now in the Daimler Roadliner p.s.v. Two output ratings are offered for the unit in the various Ford chassis in which the engine can be fitted and Dodge has standardized on the V8.510 on those models that were previously fitted with the Cummins V8 as standard. A new Dodge chassis offered with the Perkins V8 only is the KP1000 28-ton-gross tractive unit and one of the two Guy Big J chassis to have the engine is a similar model. A second Big J is a six wheeler for truck mixer applications while the new Unipower 4 x 4 tractor has the engine and a completely revised specification.

More changes to models are featured on the Guy stand than probably any other at Earls Court. I have referred to the export six-wheeler, the two Perkins-engined models and the 16-ton four-wheeler with Leyland 410 engine. On all these and on the other vehicles there have been changes in various details and the most important relates to braking. It may seem that I am obsessed with braking but this is one of the most frequent subjects of conversation in the industry and it is unfortunate from an operator's viewpoint that some attempt at standardization of system has not been made in the industry. One needs to be something of an electrician to understand the pipework diagrams for many of our air-brake layouts and a lot of this is completely unnecessary.

Leyland is to be commended for going to a relatively simple system for its new models with spring brakes providing for parking and secondary efficiencies. And Guy has done a similar thing but in my view gone one better by applying the secondary brake in most cases to both axles of its four-wheelersboth tractive units and rigids. With the sixwheelers the spring brakes (for secondary and parking) are on the front and rearmost axle and on the eight-wheeler only the front axle is left out for this function.

I would like to see the new Guy practice adopted by all manufacturers for not only does this seem to give a more intelligent approach to the subject of system design but it also accepts the responsibility for the tractive unit of an artic to provide at least its fair share of the braking for the secondary system. Too often one has had the impression that the chassis maker has been happy to get away with his minimum responsibilities and rely on the trailer maker to provide for most of the secondary efficiency. An example of this is seen on the AEC six-wheeled tractive unit on display where the secondary brakes for the chassis are applied to the front axle only, even though a simple modification to the valves and pipework would allow at least one of the rear axles to be powered at the same time.

On the passenger vehicle front, the major interest is on the Daimler stand with the 36ft Fleetline chassis, the Roadliner with Perkins V8 engine and the bodied CR-36 double-deck chassis which has an offset rear vee engine located longitudinally. The 3611 single-deck Fleetline is making its first appearance at Earls Court and has the uprated Daimatic semi-automatic gearbox. As well as the chassis there is a bodied example and with it a Perkins-engined Roadliner with the optional rubber suspension—leaf springs are now standard and another option is air suspension.

The CR-36 is a low-height double-decker chassis and is shown fitted with a 3611 Northern Counties 93-passenger body-86 seats. Off-setting of the engine—a Cummins V6 in the exhibit—by 13.1in. allows a rear entrance and staircase. In this respectthe new model gives the same facilities as the Bristol VRL introduced in 1966 but, like it, does not strictly meet the requirements of the Standard-Bus Grants Scheme. It seems a pity that the future of this layout may be jeopardized when it gives particular advantages over transverse-engined types. This is the version of the VR that Bristol is showing this time and accompanying the VRT on the Bristol stand is a bodied LH seen for the first time at the Commercial Motor Show—and fitted with the optional Leyland 0.400 diesel engine. The new Ford and AEC p.s.v. have been referred to and the remaining passengervehicle interest on British chassis-makers' stands is in the bodied Atlantean shown by Leyland which has a new control system for the fully-automatic transmission—based on a Self Changing Gears design.

Them are, however, two other chassis makers with one passenger vehicle each— both the German companies Mercedes-Benz and Bussing. Neither model is new but the Mercedes-Benz 0.302 luxury coach has recently been granted a Certificate of Fitness and one of the differences from the model sold in Germany is that it has British seats. The Bussing Prifekt seen for the first time in the UK is in the demonstra tion area and underwent its first Certificate of Fitness test immediately before making the journey to Earls Court but no details are obtainable about the outcome.

Mercedes-Benz also has a good display of goods chassis on its stand, the most important being the right-hand version of the LPS 1923 38-ton-gross four-wheeled tractive unit. This model is also making its first appearance in the UK and has a 255 bhp gross six-cylinder diesel driving through a 12-speed splitter gearbox (the option in the chassis). Standard equipment on the LPS 1923 includes power steering and the Show example has a high-quality flat-front sleeper cab.

The two goods chassis on the Bussing stand are technically interesting. Both are forward control designs—a 38-ton-gross tractive unit of conventional layout and a 16-ton four-wheeler with underfloor engine— but it is open to speculation how the make will fare in the UK market which is already rather crowded.

Other overseas vehicles exhibited at Earls Court are the German Magirus and Italian Fiat. The former make now has a better chance since the link with Seddon and formation of Seddon-Deutz Ltd. but again no new models are displayed. There are two-axle and three-axle tractive units for 38 tons gross and a 26-ton-gross 6 x 6 dumptruck chassis. But the distinction of having the only municipal-type fire appliance on a chassis stand goes to Seddon-Deutz. It is one of an order for this type of machine from Glasgow. All the Magirus chassis displayed are, of course, unique at the Show in having aircooled vee diesels.

Fiat has not made, and says it is not planning to make, any steps to enter the UK market. The firm shows a range of current goods models which are fairly heavy by UK standards and likely to need special alterations to meet our conditions.

With all the important exhibits in the chassis and other ground-floor sections of Earls Court, it is possible for visitors to overlook the importance of a walk around the gallery. Much of what is new on the components stands has already been dealt with in CM but manufacturers were not always able to give full details of their plans before the opening day. But it is in the components section that many developments not yet taken up by chassis manufacturers can be seen. This applies to braking but particularly to engines where the uprated Gardner LW units can be seen and the Cummins Custom Torque engine is having its first airing in this country.

The term Custom Torque is used by Cummins to explain that the torque of the engine has been tailored to match customer demands. The NHCT-CT shown by Cummins is a turbocharged six-cylinder in-line diesel and while it gives the same output of 240 bhp as the standard NHK 250, the maximum torque output is increased substantially and moved back from 1,500 rpm to 1,200 rpm. There are three output versions of the engine-240, 255 and 270 bhp—but the two higher have a lower torque output than the 240 bhp engine. In this case the torque is 900 lb. ft. and the maximum output is maintained more or less constant from 1,750 rpm up to the maximum governed speed of 2,100 rpm. The two main advantages of the Cummins unit are improved fuel economy and longer life and less gear changing because of the high low-speed torque. The engine can, in other words, give a road performance equal to an engine developing a much higher power output.