DON'T TRY TO PASS TH .M.5 ON THE MP

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

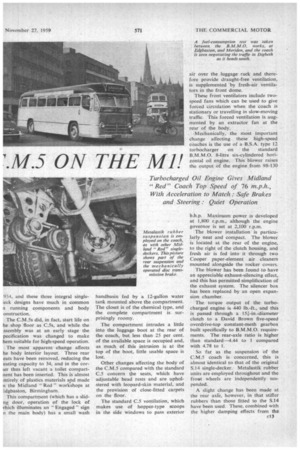

SUPREMELY safe, quiet and comfortable at speeds in excess of 70 m.p.h., the new B.M.M.O. C.M.5 express coach is probably the finest and most modern example of a highspeed passenger vehicle in regular service anywhere in Europe, if not the world.

A test of this vehicle under motorway conditions showed it to have a genuine top speed of at least 75 m.p.h., at which speed it was as steady as a rock and as controllable as the most safe of hand-built sports ears. Passengers who may be perturbed at the thought of being carried at such a pace need have no fears.

Deceptive Speed

Indeed, so quiet and smooth is the coach that only those who are able to see the rather diminutive speedometer would be aware of anything like the speed at which they were travelling.

It might be thought that this performance has been obtained at the sacrifice of economical operation, but this is by no means the case. A fullthrottle 35-mile fuel-consumption test • made along a section of Ml, but starting and finishing off it, showed an average consumption rate of 15.1 m.p.g. In town traffic 16.8 rrip.g. was obtained on a 14-mile test from the centre of Birmingham southwards.

This kind of economy explains how it is possible for the Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Co., Ltd. to run these coaches on Birmingham. London services in a scheduled time of 3 hours 25 minutes at a return fare of £1 is. 3d. This is almost half the second-class rail fare, and less than c12 a third of the cheapest airline return excursion fare.

Such a schedule obviously cannot be attempted unless the operators can be assured that the vehicle is going to be safe at high speeds. In this respect Midland "Red" are leading the field by their use of disc brakes.

Unfortunately, because of a loose test load, I was not able to conduct' my own brake tests, as is usual when compiling such reports, but figures taken by Midland "Red " engineers can be relied upon.

The figures they have obtained from speeds of 20, 30 and 60 m.p.h. are recorded in the data panel. Such data by themselves, however, do not necessarily imply high-speed safety over a 65-mile stretch of motorway: fade resistance is even more important.

On the M.I.R.A. test ground, 200 stops were made from 30 m.p.h. at half-minute intervals. Each averaged 55 per cent efficiency with 135 lb. pedal pressure. Then a 'crash" stop from the same speed produced a deceleration-meter reading only 3 per Cent, less than with cold discs. A' further fade test made on th same 2.8-mile track involved makin three brake applications from 60 to 2 m.p.h. on each circuit for three horn continuously. During this series c tests the pedal effort was kept cor stant and the deceleration rat remained constant with it So far as acceleration is concerne( the C.M.5 reached 50 m.p.h. from standstill in 42.4 seconds and 60 m.p.I 22.6 seconds later. This degree c acceleration is comparable with th practised by most average car driven and is a guarantee that the coach coul never be accused of causing traffi hold-ups.

Ten C.M.5 coaches have been bui for service on the Midland "Red motorway'.run between Birminghar and London. They are based on th C.5 coach which was introduced i September last year, and of which 3 are in operatiOn. The C..5 in turn based on the S.14 bus introduced i 954, and these three integral single1eck designs have much in common a running components and body onstruction.

The C.M.5s did, in fact, start life on he shop 'floor as C.5s, and while the ,ssembly was at an early stage the pecification was changed to make hem suitable for high-speed operation.

The most apparent change affects he body interior layout. Three rear eats have been removed, reducing the eating capacity to 34, and in the corLer thus left vacant a toilet compactnent has been inserted. This is almost :ntirely of plastics materials and made n the Midland " Red " workshops at Edgbaston, Birmingham.

This compartment (which has a slidng door, operation of the lock of vhich illuminates an " Engaged " sign n the main body) has a small wash handhasin fed by a 12-gallon water tank mounted above the compartment. The closet is of the chemical type, and the complete compartment is surprisingly roomy.

The compartment intrudes a little into the luggage boot at the rear of the coach, but less than 25 per cent. of the available space is occupied and, as much of this intrusion is at the top of the boot, little usable space is lost.

Other changes affecting the body of the C.M.5 compared with the standard C.5 concern the seats, which have adjustable head rests and are upholstered with leopard-skin material, and the provision of close-fitted carpets on the floor.

The standard C.5 ventilation, which makes use of hopper-type scoops in the side windows to pass exterior

air over the luggage rack and therefore provide draught-free. ventilation, is supplemented 'by fresh-air ventilators in the front dome.

These front ventilators include twospeed fans which can be used to give forced circulation when the coach is stationary or travelling in slow-moving traffic. This forced ventilation is augmented by an extractor fan at the rear of the body.

Mechanically, the most important Change affecting these• high-speed coaches is the use of a, B.S.A. type 12 turbocharger on the standard B.M.M.O. 8-litre six-cylindered horizontal oil engine. This blower raises the output of the engine from 98-130

b.h.p. Maximum power is developed at 1,800 r.p.m., although the engine governor is set at 2,100 r.p.rn.

The blower installation is particularly neat and compact. The blower is located at the rear of the engine, to the right of the clutch housing, and fresh air is fed into it through two Cooper paper-element air cleaners mounted alongside the rocker covers.

The blower has been found to have an appreciable exhaust-silencing effect, and this has permitted simplification of the exhaust system. The silencer box has been replaced by an open expansion chamber.

The torque output of the turbocharged engine is 440 lb.-ft., and this is passed through a 151-in.-diameter clutch to a David Brown five-speed overdrive-top constant-mesh gearbox built specifically to B.M.M.O. requirements. The rear-axle ratio is higher than standard-4.44 to 1 compared with 4.78 to 1.

So far as the suspension of the C.M.5 coach is concerned, this is almost identical to that of the original S.14 single-decker. Metalastik rubber units are employed throughout and the frout wheels are independently suspended.

A slight change has been made at the rear axle, however, in that stiffer rubbers than those fitted to the S.14 have been used. These, combined with the higher damping effects from the Armstrong telescopic units, give the rear-end stability necessary for highspeed operation.

Girling disc brakes. are used at all wheels, and although these are the same as on previous single-deckers the boost effect given by the Lockheed continuous-flow hydraulic system is higher than on the earlier coaches.

This is because the servo pump is driven off the rear of the gearbox and therefore its output is proportional to road speed. This is a particularly useful feature of this system: the faster the vehicle, so the more powerful become the brakes.

Tyres are important on a vehicle such as this. The 10 C.M.5s at present in operation have been fitted with Dunlop Highway 9.00-20 in. (12-ply) tyres on the front wheels, and Awin 9.00-20 in. (10-ply) tyres at the rear. All the wheels are statically balanced, and the front and rear tyre pressures are 85 p.s.i. and 45 p.s.i. respectively.

The Dunlop Highway tyre has been chosen because it has a thinner tread (-14 than the type of tyre normally used on passenger vehicles, and this gives better heat dissipation.

The coach offered to me for test was No. 4809, and it had been taken out Of service especially for my benefit. It had covered about 4,000 miles and its unladen kerb weight was 1 qr. under 7 tons. The dry taxation weight was 6 tons 13+ cwt.

A ton of cast-iron blocks had been Loaded in the gangway to provide a limited amount of test load, and in addition there was some 2 cwt. of fuel in the boot for use when topping up the test tank. Thus the vehicle was carrying the equivalent of about 18 passengers and light hand baggage.

My first test was to make a fuelconsumption run from Edgbaston towards Coventry. The run was made from cold, and the route chosen took in a fair amount of town traffic. This made it impossible to use overdrive for the first 28 minutes of the 364minute 14-mile test.

This was typical of actuaL operating conditions, however, and once clea of the thick town traffic in central arii southern Birmingham, the Midlam " Red " driver took the speed up t( 50 m.p.h. until the test was finishe( on the Meriden by-pass. The resultin; consumption rate was 16.8 m.p.g whilst the average speed was 23. m.p.h.

From Meriden the coach was takei to a lay-by about half a mile nortl of the roundabout marking the star of the M45 motorway spur at Dun church. Here the test tank was toppe( up again and the coach was driven a maximum speed as far as the A4: turn-off point at Nether Heyford.

When starting off from Dunchurch I noted that the driver changed In from fourth to fifth gear at abou 55 m.p.h., although the coach will d( 60 m.p.h. in direct drive. Within tw( minutes the speed was up to 70 m.p.h. and I marvelled at the quietness o the power unit at this speed, thi; applying also to the exhaust note an the turbocharger. Similarly, although the basic C.5 )ody-shell shape has never been subected to any wind-tunnel tests, there vas a remarkable absence of wind wise. Usually in a standard private :ar, for example, wind noise becomes serious problem over 70 m.p.h. and an do much to detract from passenger :omfort.

The A45 turn-off point was reached 6f minutes after leaving Dunchurch, ind the coach came to rest a minute ater on the bridge running across Ml.

then drove it back towards Dunturch and was fascinated by the .tability of the vehicle when running it full speed.

• 76 m.p.h. on Centre Lane

In keeping with the normal procelure of Midland " Red " drivers on NIL I used the centre lane of the road md the steering needed hardly my correction, even when driving flat )ut at 76 m.p.h. I could have safely oaken my hands off the steering wheel, )ut considered it better not to set a )ad example!

The .35-mile round trip occupied a total time of 35 minutes, of which ipproximately three minutes were ;pent off the motorway, accelerating Ind decelerating for the start and inish at each end. Thus the motorway section itself was in effect covered at an average speed of over 64 m.p.h.

Acceleration tests were carried out pn a level stretch of the A45, and par;icularly impressive figures were pbtained when making the standingitart tests. The direct-drive runs were Made between 20-60 m.p.h. because, although the engine would pull reasonably smoothly with that ratio engaged at a road speed of 10 m.p.h., it was felt that, in view of the high rear-axle ratio, to take the figures from 10 m.p.h. would not have been a fair test.' The maximum gear speeds observed were as follows: second, 22 m.p.h.; third, 38 m.p.h.; fourth, 60 m.p.h.; and fifth, 76 m.p.h.

Drivers of this coach could ask for little more by any standards of heavy-vehicle driving. The steering is pleasantly light without being vague, and even over rough surfaces there was no wheel kick, which indicated the success of the independent front suspension and steering-layout design.

Although because of the transmission-driven boost pump the brakes are a little heavy to operate at low speeds, as the speed increases the effort required reduces and at no time is it exceptional.

The lantern-type windscreen gives an exceptional range of forward vision in addition to 'having valuable antidazzle properties. No curved panels are used in the screen assembly. Indeed, the only curved glazing in the coach is at the rear quarters, and these panels are of Perspex.

From the passenger's angle, the coach is a most pleasant vehicle to travel in and well above the usual standard to be found in this country. Interior finish is light and cheerful and the seats are quite comfortable.

Quietness has received close attention, the floor carpeting helping to reduce the transmission of engine noise. Further sound deadening is given by the use of perforated-aluminium ceiling panels with Bondacoust absorption material between them and the one-piece plastics roof moulding.

No power-unit vibration is transmitted to the passenger compartment throughout the engine range. This is particularly commendable in view of the integal construction of the vehicle. The engine-gearbox unit has a five-point mounting, one connection being at the front, two at the clutch housing and two at the rear of the gearbox.

Suspension Admirable

The wheel suspension behaved admirably and on the motorway absorbed all the minor road shocks. The slight pitching experienced at high speeds was in no way uncomfortable nor liable to provoke travel sickness among passengers—an important matter on high-speed services.

There was no time to conduct maintenance on the vehicle, even if it had needed it, but I did inspect the underside. I could see that all the components needing regular attention are well placed for pit servicing. The rubber suspension reduces the amount of greasing necessary, and there are only 26 lubrication nipples on the vehicle.

Three of these are on the propeller shaft, 12 on the steering linkages and king-pins, and the others are split into two groups, serving pedal controls at the front and the engine-control linkages at the rear.

The disc brakes offer appreciable maintenance economies, only one man-hour being required to change the friction pads on a complete vehicle, compared with a minimum of eight man-hours to change the linings of drum brakes.

Friction-material life cannot be determined yet, but is expected to be in excess of 50,000 miles, which would be a clear 25 per cent, improvement over equivalent drum-brake linings.