• FORD VAN POINTERS.

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By R. T. Nicholson (Author of "The Book of the Ford").

DRIVERS of Ford ton trucks have often told me that they would welcome a little more attention on my part to their particular needs. They think that I have given altagether too much space to the problems of the van driver.

Perhaps they are right: perhaps I have ; but, after all, these are Ford van pointers, so that I might be excused for giving my attention mainly to the van. "Stick to your subject" is a pretty good motto.

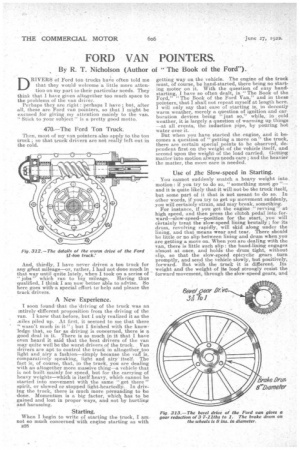

470.—The Ford Ton Truck.

Then, most of my van pointers also apply to the ton truck ; so that truck drivers are not really left out. in the cold.

And, thirdly, I have never driven a ton truck for any gileat mileage—or, rather, I had not done much in that way until quite lately, when I took on a series of " jobs " which ran to big mileage. Having thus qualified, I think I am now better able to advise. So here goes with a special effort tohelp and please the truck drivers.

A New Experience.

I soon found that the "driving of the truck was an intirely ,different proposition from the driving of the van. I know that before, but I only realized it as the miles piled up. At first, it seemed to me that there "wasn't much in it " ; but I finished with the knowledge that, so far as driving is concerned, there is a good deal in it. There is BO much in it that I have even heard it said that the best drivers of the van may quite well be the worst drivers of the truck. Van drivers are apt to control the truck in altogether too light and airy a fashion—simply because the vaM is, comparatively speaking, light and airy itself. The fact is, of course, that, in the truck, you are dealing with an altogether more massive thing—a vehicle that is not built mainly for speed, but for the carrying of heavy weights—which is itself heavy, which cannot be started into movement with the same "get there" spirit, or slowed or stopped light-heartedly. In driving the truck, there is much more persuading to be done. Momentum is a big factor, which has to be gained and lost in proper ways, and not by hurtling and harassing.

Starting.

When I begin to write of starting the truck, I am. not so much concerned with engine starting as with n28

getting way on the vehicle. The engine of the truck must, of course, be hand-started, there being no starting motor on it. With the question of easy handstarting, I have so often dealt, in " The Book of the Ford," "The Book of the Ford Van," and in these pointers, that I shall not repeat myself at length here. I will only say that ease of starting is, in decently warm weather, merely a question of ignition and carburation devices being just so," while, in cold weather, it is largely a question of warming up things —at all events, the induction pipe, by pouring hot water over it.

But when you have started the engine, and it becomes a question of " getting a move on" the truck, there are certain special points to be observed, dependent first on the weight of the vehicle itself, and second upon the weight of the load carried. Getting matter into motion always needs care ; and the heavier the matter, the more care is needed.

Use of the Slow-speed in Starting.

. You cannot suddenly snatch a heavy weight into motion : if you try to do so, "something must go "— and it is quite likely that it will not be the truck itself, but some part of it that is not meant to do so. In other words, if you try to get up movement suddenly, you will certainly strain, and may break, something.

i For instance, f you get the engine " revving ' at high speed, and then press the clutch pedal into forward—slow-speed—position for the start, you will 4rtainly treat the slow-speed lining brutally ; for its drum, revolving rapidly, will skid along under the lining, and that means wear and tear. There should be little or no slip 'between lining and drum when you are getting a move on. When you are dealing with the van, there is little such slip : the band-lining engages almost at once, and holds the drum tight, without slip, so that the slaw-speed epicyclic gears turn promptly, and send the vehicle slowly, 'but positively, forward. But with the truck it is different. Its weight and the weight of its load strongly resist the forward movement, through the slew-speed gears, and if there is high engine speed at the moment the gears will remain at rest, while the slow-speed drum will slither along under the slow-speed band lining. This means that the lining will be short-lived, and the replacement of bands is a job that costs money, to say nothing of its causing much inconvenience and loss of earning powers while the work is being done. So, in starting have the engine running only at such speed as will enable you to pick up the slow-speed without Stopping the engine. Then you will get prompt engagement of the slow-speed, and momentum will be slowly but surely picked up. If you feel the slow-speed slipping—if, that is, you do not promptly get way on when you engage slow-speed by forward movement of the pedal, the probability is that you have too much engine speed. Keep it down. And when you have the truck moving, keep the slow-speed pedal pressed hard forward : do not let the band slither on the drum through feeble foot-pressure. Of course, there is a certain amount of humouring to be done at this moment ; but do not allow any more slip than is necessary to keep the engine going.

Picking Up the High-speed.

Do not get "into high" too soon, or with too little way on the truck. On a level road, or downhill, it will, of course, be easier to get "into high" than when you are running uphill. A good deal., too, depends on the weight of your load. No hard-and-fast rule can, therefore, be laid down, except this : Never get " into high" if the change up worries the engine unduly ; get up more speed through "slow," A speed of from six to eight miles an hour ." on slow" is ordinarily needed before " high" is picked up.

Speed on the Road.

Now we come to the very heart of the subject.. The Ford ton truck is not built for speed: it is meant for the carriage of loads. When driving the truck, give up all thought of a time job. Go slow. Of course, slowness and speed are relative terms. You must "get there" some time, even if you are not on a time job ; and there are limits to the "some time." What about it ?

The van driver runs, on the open road, on nonstop stretches, at 25-30 miles an hour. He feels that that speed suits his engine best.

The truck driver cannot—or should not—run at any such speed at any. time. His best speed is, on the average, just about one-half that which the van driver

finds best. At the outside, the truck should be driven not more than 18 miles an hour, and 15 is a far safer limit.

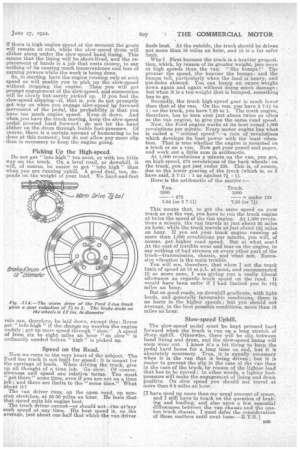

Why I First because the truck is a heavier proposition, which, by reason of its greater weight, jars more at high speeds than the van. "She bumps!" The greater the speed, the heavier the bumps : and +lie bumps tell, particularly when the load is heavy, and pot-holes aboru.nd. You can bump an ounce weight down again and again without doing much damage ; but when it is a ton weight that is bumped, something has to go. Secondly, the truck high-speed gear is much lower than that of the van. On the van, you have 3 7-11 to 1: on the truck, you have 7.25 to 1. The truck engine, therefore, has to turn over just about twice as often as the van engine, to give you the same road speed.

Now, the Ford engine works at its best round 1,000 revolutions per minute. Every motor engine has what is called a critical speed' —a rate of revolutions which develops its best power with the least vibration. That is true whether the engine is mounted on a truck or on a van. Now get your pencil and paper, and work out a little sum in arithmetic.

At 1,000 revolutions a minute on the van, you get, on high-speed, 275 revolutions of the back wheels : on the truck, you get just under 138. This is of course, due to the lower gearing of the truck (which is, as I have said, 3 7-11 : 1 as against 7+ : 1).

Here is the arithmetic of the matter :— Van. Truck.

1 1000 000 275 = under 138 — —

3.64 (or 3 7-11) ,7.25 (or "71)

This means that, to get the same speed on your truck as on the van, you have to run the truck engine at twice the speed of the van engine. At 1,000 revolutions a minute, the van travels at just about 25 miles an hour, while the truck travels at just about 124 miles an hour. If you set your truck engine running at more than 1,000 revolutions per miniite, you will, of course, get higher road speed. But at what cost? At the cost of terrible wear and tear on the engine, to say nothing of bad stresses on every other part of the truck—transmission, chassis, and what not. Excessive vibration is the main trouble.

You will see, therefore, that when I set the truck limit of speed at 18 m.p.h. at most, and recommended 15 as more sane, I was giving you a really liberal allowance as regards truck speed on the road. It would have been safer if I had limited you to 124 miles an hour.

But on good roads, on downhill gradients, with light loads, and generally favourable conditions, there is no harm in the higher speeds ; but you should not average, in the best possible conditions, snore than 15 miles an hour.

Slow-speed Uphill.

The slow-speed pedal must be kept pressed hard fprsvard when the truck is run on a long stretch of 'steep uphill. Otherwise, -there will be slip between band lining and drum, and the slow-speed listing will soon wear out. I know it's a bit tiring to keep the pedal hard home for a long time on end, but it is absolutely necessary. True, it is equally necessary when it is the van that is being driven ; but it is easier to prevent the sibs in the case of the van than k

in the case of the trucby reason of the lighter load that has to be moved : in other words, a lighter footpressure will make the engagement of lining and drum positive. On slow speed you should not travel at more than 6-8 miles an hour.

[I have used up more than my usustil amount of space, and I still have to touch on the question of braking and loading, and also upon a few essential differences between the van chassis and the one.. ton truck chassis. I must defer the consideration of these matters until next issue.—R.T.N.1