DE P END

Page 22

Page 24

Page 25

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

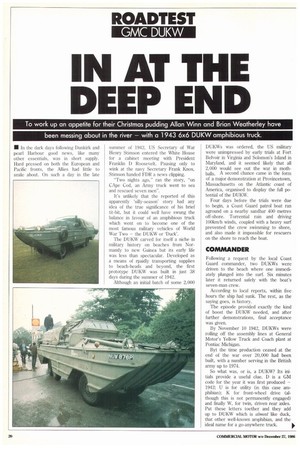

To work up an appetite for their Christmas pudding Allan Winn and Brian Weatherley have been messing about in the river — with a 1943 6x6 DUKW amphibious truck.

• In the dark days following Dunkirk and pearl Harbour good news, like many other essentials, was in short supply. Hard pressed on both the European and Pacific fronts, the Allies had little to smile about. On such a day in the late summer of 1942, US Secretary of War Henry Stirnson entered the White House for a cabinet meeting with President Franklin I) Roosevelt. Pausing only to wink at the navy Secretary Frank Knox, Stirnson handed FDR a news clipping.

"Two nights ago," ran the story, "on CApe Cod, an Army truck went to sea and rescued seven men".

It's unlikely that the reported of this apparently 'silly-season' story had any idea of the true significance of his brief tit-bit, but it could well have swung the balance in favour of an amphibious truck which went on to become one of the most famous military vehicles of World War Two — the DUKW or 'Duck'.

The DUKW carved for itself a niche in military history on beaches from Normandy to new Guinea but its early life was less than spectacular. Developed as a means of rpaidly transporting supplies to beach-heads and beyond, the first prototype DUKW was built in just 38 days during the summer of 1942.

Although an initial batch of some 2,000 DUKWs was ordered, the US military were unimpressed by early trials at Fort Belvoir in Virginia and Solomon's Island in Maryland, and it seemed likely that all 2,000 would see out the war in mothballs. A second chance came in the form of a major demonstration at Provincetown, Massachusetts on the Atlantic coast of America, organised to display the full potential of the DUKW.

Four days before the trials were due to begin, a Coast Guard patrol boat ran aground on a nearby sandbar 400 metres off-shore. Torrential rain and driving 100knnih winds, coupled with a heavy surf prevented the crew swimming to shore, and also made it impossible for rescuers on the shore to reach the boat.

COMMANDER

Following a request by the local Coast Guard commander, two DUKWs were driven to the beach where one immediately plunged into the surf, Six minutes later it returned safely with the boat's seven-man crew.

According to local reports, within five hours the ship had sunk. The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

The episode provided exactly the kind of boost the DUKW needed, and after further demonstrations, final acceptance was given.

By November 10 1942, DUKWs were rolling off the assembly lines at General Motor's Yellow Truck and Coach plant at Pontiac Michigan.

Byt the time production ceased at the end of the war over 20,000 had been built, with a number serving in the British army up to 1974.

So what was, or is, a DUKW? Its initials provide a useful clue. D is a GM code for the year it was first produced — 1942; U is for utility (in this case amphibian); K for front-wheel drive (although this is not permanently engaged) and finally W, for twin, driven rear axles. Put these letters toether and they add up to DUKW which is almost like duck, that other well-known amphibian, and the ideal name for a go-anywhere truck.

The DUKW was, however, by no means a unique vehicle — rather a seagoing version of the famous GMC 4.5 litre petrol-engined CCKW 6x6 2.5 tonnepayload truck which entered service in 1941.

It used the same engine, gearbox, transfer case, drive shaft, axles and braking system as the CCKW, all fitted in a specially-developed steel marine hull designed by American yacht builder Rod Stephens, whose work had won many trophies in national and international boating competitions.

The advantage of basing the DUKW on the conventional CCKW 6x6 truck was that around 85% of its components were tried and tested.

The hull shape of the DUKW was, not surprisingly, a compromise, allowing it to operate successfully on both land and water.

DUKW hulls were built out of 1.5mm steel plate with a thicker 2.7mm section for the bow. To reduce weight, however, the driver's compartment trim, and loaddeck were made of timber.

With the DUKW's large, open cargo area and relatively low freeboard, it soon became obvious that a highly efficient bilge pumping system would be essential — and unlike that of a conventional boat it would need to withstand the rigours of a dual-purpose operation with the truck driving through mud and sand as well as water.

The solution was provided by three pumps — two of which are chain-driven from the main transfer case and water transfer case respectively — and a hand pump, for use when the main propshaft is not turning.

The main pumps cuts in automatically when more than 250min of water collects in the bilges, although when all the pumps are operated the system is designed to handle more than 8181iUrnin (180 gallons), which is enough to cope with water pour

ing in through a 75mm shell hole in the hull!

One of the biggest problems in the development of the DUKW was how to protect and seal the driveline, in particular the various drive shafts.

It was found that marine operations chilled the air in the axle housings so quickly that the resulting pressure differential forced water past conventional seals.

To overcome this, vents were fitted and double-lipped seals were installed on all pinion shafts, rear hubs and pillow blocks. The DUKW's propellor shafts up to the first rear axle were enclosed in a tube.

The actual driveshaft system is unusual on both the CCKW and DUKW; instead of a drive-through differential on the second axle of the double-drive rear bogie, the DUKW has two prop shafts emerging from the main transfer case.

HEADACHE

A short unit runs directly into the second axle, while a longer shaft is linked via a pillow block into the third axle.

Under normal conditions the DUKW is a 6x4, but it can be converted into a 6 x 6 by engaging a dog clutch in the transfer case.

Cooling the DUKW's 71KW (95hp) engine was a major headache — obviously it could not have a radiator at the front open to water. Instead, air is drawn into the forward engine compartment from behind the driving area through a selection of gratings and baffles.

Despite a larger fan and reverse flow, however, the DUKW's fan still uses no more power than that of the CCKW truck. Exhaust air from the engine is vented into the forward compartment and out through ports at the side of the cab.

By varying a number of internal baffles, warm air can be circulated around the different compartments and below the floor to prevent the bilge and pumps freezing up.

To prevent engine overheating when DUKWs were driven far inland, an auxil iary air scoop was originally fitted, but disasters at sea, caused by leaving it open, soon caused its removal!

With DUKW's landing on a variety of landing grounds, from soft sandy beaches to Pacific coral atolls, a controlled tyre-inflation system was fitted to the majority of models, allowing tyre pressures to be adjusted to various operating conditions.

Indeed the system could make an ordinary tyre virtually bullet-proof. Under tests when several 11.4mm (0.4541) calibre bullets were fired into a DUKW tyre backed up by the compressor, sufficient pressure was maintained for normal use.

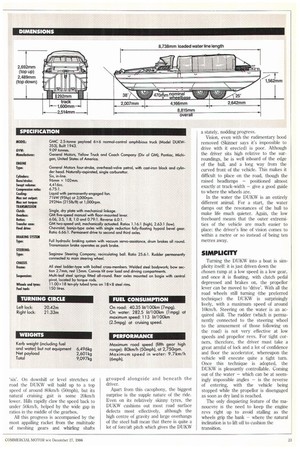

So much for the DUKW's history — but how does it perform in 1986? To find out Commercial Motor met up with dedicated DUKW owner Bob Skinner and his colleagues Alec Bilney and Mike Stallwood, for a day dabbling in the water.

Bob Skinner has had an interest in vintage military vehicles for a number of years, having previously owned a CCKW truck and playing an active part in the Invicta Military Preservation Society. In 1983 he fulfilled a long-held ambition when he bought his first DUKW for 11,750.

Built in 1943, NUW876P has been literally through the wars in more ways than one, including, it is rumoured, a night submerged in the Thames. When Skinner acquired it, "it was a wreck — the only thing that ran was the engine and that kept boiling over." A collection of leaves in the forward compartment also managed to catch fire, which didn't help matters!

During the winter of 1983 Skinner, who works as a Telecom engineer, and his friend Tony Waghorn put on a new hull, got the cooling system and brakes up to scratch and replaced a number of wheel bearings.

DRIVING

The restoration was completed a week before the 40th anniversary of D-Day on June 6 1984 and, along with a number of other British DUKW owners, Skinner made the trip over by ferry — in a DUKW it would have taken six hours, to reach France for the celebrations!

The bodywork of the DUKW is designed to keep the water out — and on first acquaintance it seems that it was also designed to keep people out as well. Access to the driving compartment is via a couple of precarious footholds which demand careful negotiation, especially in the wet.

The 'cockpit' reached via these steps is unusual to say the least, and spartan with it. The main driving controls are generally familiar once allowance is made for the left-hand drive, but scattered around are controls not normally found in a truck. Prominent among these is a lever between the seats which controls the propellor transmission.

On the road, the DUKW is about what we expected of a 45-year-old petrol-engined commercial vehicle carrying a heavy load. The clutch is surprisingly soft in feel and engagement, though fairly heavy. The gearbox — with its unusual gate which puts the first four gears in a conventional gate but the overdrive fifth and reverse in the centre — is precisely controlled by the long lever.

Acceleration is best described as leisurely, despite the vocal efforts of the GMC

a stately, nodding progress.

Vision, even with the rudimentary hood removed (Skinner says it's impossible to drive with it erected) is poor. Although the driver sits high relative to the surroundings, he is well inboard of the edge of the hull, and a long way from the curved front of the vehicle. This makes it difficult to place on the road, though the raised headlamps — positioned almost exactly at track-width — give a good guide to where the wheels are.

In the water the DUKW is an entirely different animal. For a start, the water damps out the resonances of the hull to make life much quieter. Again, the low freeboard means that the outer extremities of the vehicle are much easier to place: the driver's line of vision comes to within a metre or so instead of being ten metres away.

SIMPLICITY Turning the DUKW into a boat is simplicity itself: it is just driven down the

chosen ramp at a low speed in a low gear, and once it is floating, with clutch pedal depressed and brakes on, the propellor lever can be moved to 'drive'. With all the road wheels still turning (the preferred technique) the DUKW is surprisingly lively, with a maximum speed of around 10km/h. Steering on the water is an acquired skill. The rudder (which is permanently connected to the steering wheel to the amusement of those following on the road) is not very effective at low speeds and propellor revs. For tight corners, therefore, the driver must take a great armful of lock and a lot of confidence and floor the accelerator, whereupon the vehicle will execute quite a tight turn. Once this technique is adopted, the DUKW is pleasantly controllable. Coming out of the water — which can be at seemingly impossible angles — is the reverse of entering, with the vehicle being stopped while the propellor is disengaged as soon as dry land is reached.

The only disquieting feature of the manoue-sire is the need to keep the engine revs right up to avoid stalling as the wheels grip the bank — where the natural inclination is to lift off to cushion the

transition.