Oil makes the grades

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Modern vehicles need modern lubricant and today's lighter multigrades can provide big benefits where traditionalists are persuaded to forsake heavy oil

• A component vital to every working part in a commercial vehicle is oil, yet many hauliers shorten the life and profitability of their vehicles by using poor quality lubricants. Vehicles are now being asked to work longer and harder than before, but those extra years' use will only be trouble-free and profitable if the vehicle is run on good lubricants throughout its life, writes Richard Longworth.

In the past 15 years there has seen a steady trend away from high viscosity monograde oil toward lighter multigrades. Both oil companies and engine manufacturers have found there has been market resistance to the new generation of oil, based partly on tradition, and partly on the myth that engines run better on heavy oil.

Modern vehicles need modern lubricant, and the thickness of the oil in a can has little relation to its behaviour inside a bearing, or around a piston ring, where light oil will penetrate better than a heavy oil.

The oil pressure gauge can be a misleading instrument when discussing the relative virtues of lighter oils. Far from measuring the pressure within the bearings, which is generated hydrodynamically by the movement of the journal within the bearing, the gauge merely indicates pressure at a point close to the pump. What is more important to the bearing is the flow of oil rather than the pressure. That a lighter oil shows a lower pressure on the gauge is more likely to be indicating a higher throughput than slack bearings or a 1W0171 pump.

Thus an oil pump produces the presence of oil at the bearing, and the bearing itself produces the pressure between the working surfaces. A heavy oil showing a high pressure when starting the engine from cold, is showing how hard that oil is having to fight its way through the oilways, a fight that won't be won until the oil is hot, leaving the further reaches of the engine initially unlubricated.

Oil companies such as BP encountered initial resistance from both engine manufacturers and the haulage industry to lightweight multigrade oils. The new oil first proved its worth in combating the problems of bore polishing. This is the opposite to glazing, where a varnish builds up on the surface of the bore. With bore polish, there is little actual wear, but the finish of the bore is literally polished out.

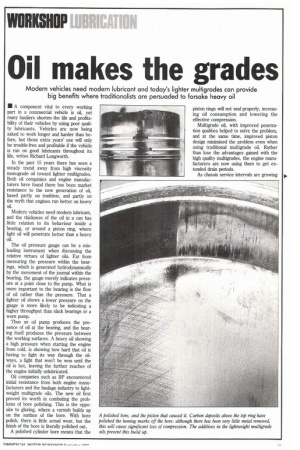

A polished cylinder bore means that the piston rings will not seal properly, increasing oil consumption and lowering the effective compression.

Multigrade oil, with improved penetration qualities helped to solve the problem, and at the same time, improved piston design minimised the problem even when using traditional multigrade oil. Rather than lose the advantages gained with the high quality multigrades, the engine manufacturers are now using them to get extended drain periods.

As chassis service intervals are growing longer, with all the implications from increased profitability, oil companies have developed products which enable the engine to run as long as the rest of the vehicle. This has meant doubling the effective life of the oil, from 15,000 to 30,000km.

The ability for an oil to run that much farther is gained not by better filtration, but by better quality additives, such as detergents and anti-oxidants. These additives ha% e a finite life, as once they have done their job, they are no longer effective. Therefore to run an engine with an extended drain period, on an oil that is designed to be changed more regularly will result in a built up of deposits, perhaps gumming up the rings, as well as increased corrosion inside the engine.

The major mechanical hazard when running an extended drain period, is a leaking fuel injector. A dripping injector will contaminate the lubricant, as well as washing it off the cylinder wall, so substantially shortening the effective working life of an engine.

Oil analysis is an increasingly popular service offered by many oil companies that can detect fuel contamination. To be strict, it is not the oil that is being analysed, but the substances mixed in with the oil.

For oil analysis to be worthwhile exercise, it must be done over a series of services, and a picture of trends built up. Apart from extreme circumstances, such as fuel contamination, a one-off analysis will give no indication as to the rate of wear of any component. All components are wearing all of the time, so only by a series of analyses can a picture be built up of engine wear rates.

It is also possible to be misled by an analysis. An engine which showed consistently high traces of copper had engineers baffled. It was not the backing material from the bigend or main bearing shells, as there was the normal quantity of lead in the oil, and to have worn through to the copper, the oil would have contained a fair amount of lead from the bearing facing. Resisting the temptation to strip the engine and investigate, the levels of copper decreased, and it was eventually decided that it had been etched from inside the oil cooler element Oil analysis systems such as the BP ROAD (routine oil analysis and diagnosis) cost around £12, which is comparable with the cost of an oil change. Although there is a 48-hour turn around, the Post Office can easily extend that to a week, so by the time you are told that a component is wearing, the vehicle may have covered a considerable distance, and that component worn out.

Oil analysis might not tea the secret of life inside your engine, but if used consistently throughout the life of the vehicle, a graph can be drawn of the rate of wear in the engine. The vehicle should not spring any nasty surprises and leave an expensive cargo stranded beside the road.

To formulate the new generation of lightweight multigrade lubricants, the oil companies have had to develop new methods of manufacture. A major problem with lighter hydrocarbons is that they are more volatile, and volatility means evaporation, and so higher consumption.

This volatility can be controlled by using extra additives, but these additives themselves have a high viscosity, so to keep the oil light, a lighter and therefore more volatile base-stock has to be used. To break out of this vicious circle, a different method of refining the base-stock has been developed: this process, as used by BP and Shell, is called Hydrocrack.

The alternative to using a Hydrocrack basestock, is to use synthetic oil. Synthetic oil, is a hydrocarbon synthesised from a hydrocarbon, that has been literally taken apart and put back together again.

One much trumpeted advantage of using 10/40 or 10/30 multigrade oil is a fuel saving. These are gained because the engine uses less energy to stir a light oil than a heavy oil, be it in the engine, gearbox or axles.

This saving, which in the case of BP Vanellus FE has been verified by the Transport Road Research Laboratory, varies between 1% and 3%. This may not sound a great deal, and can easily be lost by clumsy driving, or an under-inflated tyre. However, it is pure profit and over a year will be the equivalent to doing significantly more business.

Count the real cost

Choosing the right lubricant is as vital as fitting the right crankshaft, or piston. It will not only enable your vehicle to run reliably into its sixth or seventh year, when it owes the bank nothing, but can keep both stores and workshop buy if it has been badly lubricated.

Perhaps it is because oil tends to be stored not a million miles away from the accountant's office, many operators spend as little as possible on lubricants, so jeopardising the long-term health of its vehicles, as well as missing the opportunity to minimise their fuel cost in the shortterm. Given that the total cost of lubricants in the 10to 20-tonne class, is a mere 1.36% of running costs, this is obviously a false economy.

Although engine manufacturers were initially sceptical of the value of lighter oil, and were particularly reluctant to specify an oil more expensive or hard to obtain than the oil specified by their competitors, the tables are turning. Volvo has taken something of a lead by asking the oil companies to develop a 5W/30 specifically for its vehicles.

The operating conditions inside the different types of engine vary to the extent of needing specific lubricants. The stresses, both thermal and mechanical, generated inside a turbocharged diesel engine are far higher than those in a petrol engine. As a result the deposits are different and need different additives to clear them away.

While there are many oils on the market that will adequately lubricate an entire fleet, from the boss's Jaguar to the most powerful commercial, to get the best out of either vehicle, the best oil for that class of engine must be used. To get the best performance from your turbo diesel, there are now Super High Performance Diesel (SHPD) oils on the market such as Castrol Turbornax, BP Vaneflus FE and Mobil Delvac 1.

Major oil companies now offer far more than just lubricants. Increasingly sophisticated diagnostic techniques, oil analysis, and maintenance systems mean that an oil company can offer a range of services to the operator that will keep his vehicle running longer and more economically. To make the most of a valuable fleet of commercials, it is well worth taking advantage of these services.

Although its the major part of the vehicle, the chassis has been traditionally the Cinderella in the lubrication stakes. Where great strides have been made in lubricating the engine and transmission, the chassis has for years made do with the humble grease nipple. Now, however, help is at hand for the neglected pins and shackles that keep the vehicle running straight, in the form of centralised chassis lubrication systems.

Although many chassis manufacturers offer chassis lubrication systems as an option, and the systems can be retrofitted, trucks have yet to have them fitted as standard. The two most prominent systems on offer are from Interlube, which is a Tecalernit company and Lincoln UK, which markets the QuicIdub and Ecolub systems (both of which are pronounced as if they end in e).

Although regular and conscientious greasing is an effective method of chassis lubrication, it is very labour intensive, arid being a dirty and unpleasant job, is easily neglected. Once neglected, the damage to the chassis, and the cost of its repair can be horrendous.

Electronically controlled

Interlube offers two types of system, the XGS and the MX. The XGS is an electronically controlled system, which is operated by air, and the standard range is available with 12, 24, 36, 48 or 60 outlets on the pump. With 48 chassis lubrication points, the system costs £820 installed, and is intended for use on larger commercial vehicles.

The MX system is designed to lubricate small to mid-range commercial vehicles. Serving up to 12 lubrication points, it is powered by an electric motor activated by the ignition circuit. The motor runs on ac, which is converted from the vehicle dc supply, so avoiding the high brush and commutator wear that is a feature of dc motors. It dispenses fluid grease, and one filling will last over 500 hours of running.

The Lincoln Quicldub system differs from the Interlube XGS system as the central pumping unit has only one outlet, which feeds one or more distribution blocks. These distributor blocks reduce eight greasing points to one, which can be fed by a conventional grease gun if the reservoir and pump unit is not fitted. The distributor blocks have internal reciprocating pistons, which have no springs, seals or valves, and are powered by the hydraulic pressure from the central pumping unit.

The Ecolub, like the Interlube sytems from Tecalemit, is a multi-output pumping