THE END OF THE LINE

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

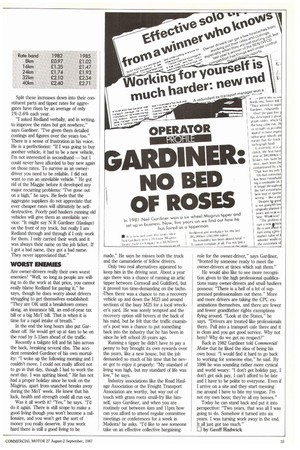

We have been following the fortunes of Neil Gardiner since 1981 when he won a brand new tipper and became an owner-driver. Now he has sold up and moved on: he explains why.

• Neil Gardiner has had enough. The man who won a free 24-tonne Magirus Deutz 232D 6x4 tipper in a BEN/Iveco competition six years ago has become disillusioned with the life of an owner-driver. Last month he finally decided to sell up.

"The work is there, but the rates are terrible," says Gardiner. Six years of being his own boss have taken their toll: "I worked every day, but I worried all the time. In the end, I just wanted more security. Every day I would get up and think, "one day, my luck is going to run out". You are constantly aware that if you don't turn up to start the job someone else will be in there — they will get your job, no matter how reliable you have been in the past."

Now the Magirus has gone: "I got a good price, as much as I was asking," says Gardiner, and the poacher has now turned gamekeeper — he is now a traffic examiner with the Trading Standards Service in Surrey, working on roadside checks.

TIPPER RATES

So what went wrong? "I don't think that anything went wrong as such," he says, "it was a combination of things." Firstly, and most importantly, he found that the tipper rates he was earning had not kept pace with inflation over the past six years: "I worked all the time for Redland at the end," he says, "and they pay the best rates going." Even so, his margins were getting slimmer all the time.

Redland, Flail and ARC are the big three aggregate suppliers and Gardiner has rate cards for them all. Redland's card is arranged on a radial basis and in 1982, when Gardiner was just getting going on his own, the rate per tonne was 97p within the 8krn (five mile) band and £1.35 within the 16krn (10 mile) band. On 1 May 1985 the rates went up to £1.02 and 21.47 respectively — but they have stayed put ever since. Over the past five years a top whack tipper man working for Redland has had a measly 5.2% to 8.8% increase on the two rates, as is shown by the following table: Split these increases down into their constituent parts and tipper rates for aggregates have risen by an average of only 1%-2.6% each year. "I asked Redland verbally, and in writing, to improve the rates but got nowhere," says Gardiner. "I've given them detailed castings and figures over the years too." There is a sense of frustration in his voice. He is a perfectionist: "If I was going to buy another vehicle, it had to be a new vehicle, I'm not interested in secondhand — but I could never have afforded to buy new again on those rates. To survive as an ownerdriver you need to be reliable. I did not want to run an unreliable vehicle." He got rid of the Maggie before it developed any major recurring problems: "I've gone out on a high," he says. He feels that the aggregate suppliers do not appreciate that ever cheaper rates will ultimately be selfdestructive. Poorly paid hauliers naming old vehicles will give them an unreliable service: "It might say N R Gardiner (Haulage) on the front of my truck, but really I am Redland through and through if I only work for them. I only carried their work and it was always their name on the job ticket. If I got a bad name, they got a bad name. They never appreciated that."

WORST ENEMIES

Are owner-drivers really their own worst enemies? "Well, so long as people are willing to do the work at that price, you cannot really blame RedLand for paying it," he says, though he does worry about drivers struggling to get themselves established: "They are OK until a breakdown comes along, an insurance bill, an end-of-year tax bill or a big MoT bill. That is when it is time for a rapid intake of breath." In the end the long hours also put Gardiner off. He would get up at 4am to be on the road by 5.15am ahead of the traffic. Recently a tailgate fell and hit him across the back, breaking several ribs. The accident reminded Gardiner of his own mortality: "I woke up the following morning and I couldn't move. I could not really afford not to go in that day, though I had to work the next day. I was spitting blood." He has not had a proper holiday since he took on the Maginis, apart from snatched breaks away during the MoT week. He knew that his luck, health and strength could all run out Was it all worth it? "Yes," he says. "I'd do it again. There is still scope to make a good living though you won't become a millionaire, and you won't get the sort of money you really deserve. If you work hard there is still a good living to be made." He says he misses both the truck and the camaraderie of fellow drivers. Only two real alternatives appeared to keep him in the driving seat About a year ago there was a chance of running an artic tipper between Cornwall and Guildford, but it proved too time-demanding on the tacho. 'Then there was a chance to run a recovery vehicle up and down the M23 and around sections of the busy M25 for a local wrecker's yard, He was sorely tempted and the recovery option still hovers at the back of his mind, but he felt that the traffic examiner's post was a chance to put something back into the industry that he has been in since he left school 20 years ago. Running a tipper he didn't have to pay a penny to buy brought its own rewards over the years, like a new house, but the job demanded so much of his time that he never got to enjoy it properly: "My standard of living was high, but my standard of life was low," he says. Industry associations like the Road Haulage Association or the Freight Transport Association are worthy, but way out of touch with grass roots small-fry late him self Gardiner, and when you are routinely out between 4am and 1 lpm how can you afford to attend regular committee meetings or conferences for a week in Madeira? he asks. "I'd like to see someone take on an effective collective bargaining role for the owner-driver," says Gardiner, "fronted by someone ready to meet the owner-drivers at times which suit them." He would also like to see more recognition given to the high professional qualifications many owner-drivers and small hauliers possess: "There is a hell of a lot of suppressed professionalism out there." More and more drivers are taking the CPC examinations themselves, and there are fewer and fewer grandfather rights exemptions flying around. "Look at the States," he says. "Drivers are treated like professionals there. Pull into a transport cafe there and it is clean and you get good service. Why not here? Why do we get no respect?" Back in 1982 Gardiner told Commercial Motor that he liked the idea of being his own boss: "I would find it hard to go back to working for someone else," he said. By 1986 he was sounding rather more cynical and world weary: "I don't get holiday pay, I don't get sick pay, I can't afford to be late and I have to be polite to everyone. Even if I arrive on a site and they start messing me around I have to bite my tongue. I'm not my own boss: they're all my bosses." Today he can stand back and put it into perspective: "Two years, that was all I was going to do. Somehow it turned into six years_ I was turning work away in the end. It all just got too much."

by Geoff Hadwick