Road Test of D31:10

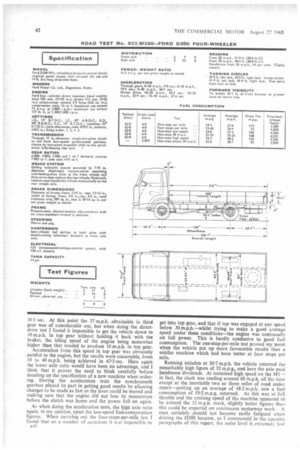

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BY

R. D. CATER, A m Inst B E AT the last Commercial Motor Show there was considerable evidence that driver comfort had been given • lot of attention, and when in April this year the Ford Motor Co Ltd. announced its new D range of commercial vehicles it was immediately evident that it was not behind its competitors in this respect. Among the many vehicles in the D range, which includes types from 2-ton capacity up to tractive units capable of handling g.v.w. of almost 19 tons, there is, near the bottom end of the scale, the D300 3-tonner which is the subject of this test report.

Incorporating all the desirable features of its larger brothers tested earlier this year the D300 has not the disadvantages that were apparent with those machines, it being adequately powered and very favourably economical. Although it is fitted with the standard version of the tilt cab the noise level is extremely low and the comfort offered by the standard seating is as good as on any machine I have driven.

The vehicle tested had a 10 ft. wheelbase and was fitted with the lowest powered engine available in this model, the fourcylinder 240 cu. in. diesel. This unit produces 74 b.h.p. net at 2,800 r.p.m. and 177 lb. ft. net torque at 1,400/1,600 r.p.m., and when coupled with the Ford four-speed, direct-drive-top gearbox and driving through 4-71 to 1 rear axle, gave the vehicle a maximum road speed of 61 m.p.h. without detracting from its ability to climb hills fairly swiftly. It did, in fact, climb the test hill without needing the assistance of first gear, a most unusual occurrence with this class of vehicle.

One of the main features of the D range is the wide choice of optional equipment that can be provided. The D300 tested was completely standard except for the inclusion of a heater! demister unit and a low observation window in the nearside door. For Ito/ money this would be the specification that I would have, as I feel that the degree of comfort offered is ample. I would not choose the observation window (this is a requirement on all vehicles exported to France, it seems) as I found this of little use in handling the vehicle.

In its standard form the vehicle is not in any way austere and it offers considerably more to the driver than most vehicles in its class. Good and well-fitted mirror equipment, excellent screenwipers and washers—a must these days— an ashtray and, for the safety conscious, seat-belt anchorages are among the standard items.

The suspension is of conventional design and provides extremely good road holding under all

lditions, and although the vehicle was loaded with a flat .d, which does not show up body roll, there did not m to be any tendency towards rolling. Braking equiptit on the test vehicle was powered by a 7.75 in.-diameter ,phragm vacuum-servo, operating two-leading-shoe its on the front axle and duo-servo shoes on the rear e. The handbrake is of the multi-pull type operated by umbrella-type handle. Steering is by a worm-and-peg ering box and can be of either leftor right-hand eon there is no provision for power assistance.

There are five different forms in which the D300 can be aplied. These are as a chassis-cab; chassis with plat-m body; chassis with a drop-sided float body; as a issis with front cowl and windshield, or with just the oil. Having 7.00-16 RSC tyres, the D300 provides a Issis height of only 26.8 in., making for a suitable work; height for a driver engaged on local deliveries. Ease access to the cab, and the fact that one can get across )m the offside to the nearside without too much uggling, gives additional advantages for this type of

■ rk.

For applications where there is a requirement for con[era* more power the vehicle can be fitted with the • rd 330 cu. in. diesel engine which produces 102 h.h.p. I at 2,800 r.p.m. and 239 lb. ft. net torque at 1,400/1,600 r.m. Judging by the performance of the four-cylinder it, I cannOt imagine an application that would justify ine the 330 cu. in. engine at this e.v.w. When this unit is fitted there is a mandatory inclusion of a 12 in.-diameter clutch in place of the 11 in.-diameter one fitted with the 240 Cu. in. engine.

A point which particularly impressed me . when first taking ovei the 1)300 was the complete lack of need io get used to it. As soon as I settled in the cab I felt that immediate comfort which normally is only present in a familiar vehicle. And when starting off on the first lap of. the test which entailed traversing abut six miles of very second-class road. I again found that I was Cornpletely at home, being able to complete all the functions needed to handle a vehicle in a manner usually reserved for a machine with which one is fully conversant. In particular, the steering of this machine. 'needs comment. Seldom have I handled a Vchicle which responded so accurately as this one.

However, I thought that the .axle .ratio was a bit too high for round-the-houses work and personally would have chosen the next lowest in the available range, which is 5-29 to I. This would have probably bettered The fuel consumption when operating at 30 to 40 m.p.h. on normal roads: also, it would, have been easier to -" trickle along " when negotiating traffic. Nevertheless, the machine performed. extremely well, and for applications where ii needed to operate inter-city. entailing a fair amount of long-distance running, the gearing on the test vehicle would be' ideal.

. Acceleration tests proved that the vehicle was no sluggard, a: it 'reached 40 in.p.h: through the gears. in 1.59

361 sec. At this point the 37 m.p.h. obtainable in third gear was of considerable use, but when doing the directdrive test I found it impossible to get the vehicle down to 10 m.p.h. in top gear without holding it back with the brakes, the idling speed of the engine being somewhat higher than that needed to produce 10 m.p.h. in top gear. Acceleration from this speed in top gear was obviously painful to the engine, but the results were reasonable, from 10 to 40 m.p.h. being achieved in 47-3 sec. Here again the lower axle ratio would have been an advantage, and I think that it proves the need to think carefully before deciding on the specification of a new machine when ordering. During the acceleration tests the synchromesh gearbox played its part in getting good results by allowing changes to be made as fast as the lever could be moved and making sure that the engine did not lose its momentum before the clutch was home and the power full on again.

As when doing the acceleration tests, the high axle ratio again, in my opinion, upset the low-speed fuel-consumption figures. When carrying out the four-stops-per-mile test found that on a number of occasions it IA as impossible to get into top gear, and that if top was engaged at any speed below 30 m.p.h.---whilst trying to make a good average speed under these conditions—the engine was continually on full power. This is hardly conducive to good fuel consumption. The one-stop-per-mile test proved my point when the vehicle put up more favourable results than a similar machine which had been better at four stops per mile.

Running unladen at 30-7 m.p.h. the vehicle returned the remarkably high figure of 32 m.p.g., and here the axle paid handsome dividends. At sustained high speed on the Ml— in fact, the clock was reading around 60 m.p.h. all the time except at the inevitable two or three miles of road under repair—putting up an average of 48.2 m.p.h. saw a fuel consumption of 19-2 m.p.g. returned. As this was at full throttle and the cruising speed of the machine appeared tobe around the 52 m.p.h. mark, slightly better figures than, this could be expected on continuous motorway work. A man certainty should not become easily fatigued when driving the D300 because, as I commented in the 'opening paragraphs of this report, the noise level is extremely low

1 found it easy to carry on a normal conversation with :ompanion. Couple this with the high degree of comfort vision provided, plus good ventilation, and I feel that iriver comes off fairly well.

le pedals were very comfortable to use and, with the ption a the throttle—which had a bad tendency irds needing extra pressure to open it for the first small of its travel, when it would then go fully open with a and spoil smooth progress—they were light and nicely ed.

rake tests proved that the brakes were more than pate for the job they had to do, average retardation vs produced being 20-6 ft. per see from 20 m.p.h. and ft. per see from 30 m.p.h. On every stop except one Tapley meter showed more than 90 per cent maximum rdation and there was severe locking of all wheels: 1 the impression that there was perhaps a little too h effort being applied to the brake shoes and that taps the vehicle might have stopped just as well, and a more safely, had wheel locking not been so prevalent. !.r an, when the fade test was comPleted, this proved to he case because the Tapley meter still registered 95 per : and the tendency to lock had gone from the front els, although the rear ones. still locked. The fade-test ■ , Which because of traffic conditions had to be done n a higher speed than usual (25 m.p.h.), was completed ast about 21 ft. •

ri the handbrake test, which was completed after the ice brake tests, I found it possible to produce better res than on any vehicle I have tested to date. Several Ps made from 20 m.p.h. produced the same Tapley er reading of 54 per cent, locking the wheels on the axle on each occasion. It is unusual, to say the least, ind a small vehicle such as the D300 fitted with a mt handbrake; the one fitted to this vehicle is identical that fitted to the largest models available in this range it does its job with plenty to spare. Some people may like the method of releasing the handbrake, which has se pushed right in to partially release it and hold the ice, such as when starting on a hill, and then given a pie quarter-turn anti-clockwise to free it completely. only complaint was that it was noisy in operation,

I liked it, nevertheless. • /nlike most of the units needing a multi-pull to apply n, this one would not prove impossible to use in the nt of a service brake failure creating an emergency. full-length pull and a couple 'Of notches on the second and the wheels are locked. •

'he hill climb was done on Bison Hill,,which has an rage gradient of 1 in 10.5 and a maximum gradient of 1 6-5, and the vehicle acquitted itself very well indeed. .t length of the hill is 0.75 miles and the vehicle climbed . in 3 in. 1-5 sec., spending 1 mm. 10;5 sec, in second r, the lowest used. The minimum speed recorded was n.p.h. ' As the 'cooling system incorporates a headerk it was impossible to take engine coolant temperatures, 'there Was no sign of -overheating, even though the bient temperature was 27'C (80`F). The brake-fade test was carried aid in the usual manner, coasting down Bison at approximately. 20 m.p.h. against the brakes, and when there was no longer sufficient momentum to keep up 20 m.p.h. engaging top gear and driving against the brakes. Out of a total lime of 2 min. 14.5 sec. taken to descend the gradient, it was necessary to engage top gear for 52.5 sec, When a maximum pressure stop was made from 25.m.p.h. this produced a Tapley meter reading of 95 percent, as I commented earlier.

Climbing the hill Once more to check the ability of the machine to hold on its handbrake and start off from standstill both facing up and down. I one again had some excellent results from the handbrake. This was capable of stopping the machine dead as I-let. it roll down the hill backwards: when rolling down .forwards it locked the wheels and brought the vehicleto •a• smart halt.

I found it impossible to get• the machine rolling in second gear from a standstill, but moving off in .first gear presented no difficulty. at all. Once moving, I then found it possible to engage the next highest gear, when the speed quickly rose to 12 or 14 m.p.h. This was one section where the high axle seemed to match the conditions perfectly. A start in reverse when facing down the hill was a simple proposition.

Not only have the drivers scored with this range of vehicles, the fitting staff also have obviously been given an outfit without any of the irritating faults that have abounded on machines of days gone by. The tilt-cab is what it pretends to be. giving completely unobstructed access to the engine, front suspension and cooling system. Sensibly positioned so as to allow ease of servicing are the hydraulic reservoirs, fuse panel, flasher unit and screenvsiper motor. Only removal of the gearbox now presents a job that might not be tackled enthusiastically.

As tested the 1)300 costs £1.115. the extra price of the low observation window being £12. In chassis cab form the cost of the machine is £985.