• A Private London-Land's End Trial

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A Gruelling 645-mile Route Brings Out the Best in the A.E.C. Reliance Coach Chassis : Fast, Lively and Economical Performance in Spite of Hills and Continual Rain

by John F. Moon

AN average speed of 31 m.p.h. over a run of 645 miles would be an excellent figure for the normal private car. For a medium-engined coach it is exceptional—and more so because the journey was, for the • most part, conducted in appalling weather and included 140 miles of tortuous and hilly roads.

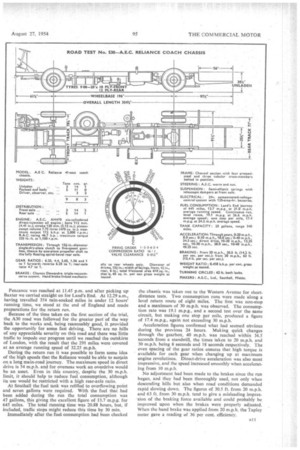

This performance was put up by an A.E.C. Reliance coach chassis on a trip from Southall, Middx., to Land's End and back. Despite torrential rain, the liveliness and easy handling of the vehicle made the journey enjoyable. The fuel-consumption return of 13.7 m.p.g. over the whole journey was also gratifying. , The Reliance has almost sports-car characteristics, with its responsive steering, quick acceleration and ability to " sit" on a slippery road surface. There were unusual opportunities of assessing hill-climbing performance during the run, as two of the most severe hills to be found on British main roads—Porlock and Lynmouth—were on the route. The showing on these hills surprised people who have seen many vehicles resort to low gear before venturing on the major slopes. , A chassis intended for coach working was borrowed for the trial, this differing from the bus version only in respect of a dropped rear frame extension and heavier rear springs to cope with the additional weight of a laden luggage compartment. Two engine sizes are available for the Reliance chassis; the difference is in the bore, and it was the larger engine, together with the highest of the alternative axle ratios, that was fitted to the vehicle tested.

This engine, the AH470, is a six-cylindered directinjection unit of 7.75 litres and has a maximum power output of 112 b.h.p. at 2,000 r.p.m., the maximum torque being 325 lb.-ft. at 1,100 r.p.m. The cylinder block and crankcase are in one piece and the block carries

n8 enewable wet liners. These have a ore of 112 mm. in the large engine ad 105 mm. in the AH410, with a orresponding decrease in power outut of 14 b.h.p, with the latter engine.

A five-speed gearbox, with inertia )ck synchromesh engagement for all ut low and reverse ratios, is bolted

) the engine flywheel housing. 'The Wes are 6.25,4.4, 2.65, 1.56 and to 1, with a reverse ratio of 6.25 >1.

The rear axle has spiral-bevel

caring with alternative ratios of 4.7, .22, 5.87 and 6.28 to 1. Twin tyres

re fitted at the rear, 9.00-20 being specified for the home market and 10.00-20 on export chassis.

On the chassis tested the braking equipment was Clayton Dewandre triple vacuum servo, with tandempiston cylinders on the front units. Girling cam-operated units are used at both axles. An air-pressure system is also available.

Iron weights were attached for the test, these weighing 5 tons 11 cwt., equivalent to a 2-ton luxury coach body and 41 passengers with heavy luggage. The gross vehicle weight was 9 tons 8f cwt., of which 3 tons 14i cwt. Was imposed on the front axle. This was 4f cwt. above the maker's recommended figure and was further increased by 31 cwt. when allowing for a driver and observer. Driving lights had been rigged up for the trip and I was to be accompanied by John Moon, Norman Tuckwell Jnr. and Charles Baxter, all of A.E.C., Ltd. Mr. Baxter travelled overnight to Penzance to be fresh for the return journey.

We set out from the works at Southall at 9 a.m., Tuckwell driving for the first spell. Ambient temperature was 63° F. and within 15 minutes the radiator temperature was recorded as 167° F., by which time we were clear of Southall town. After a three-minute traffic delay in Uxbridge, Gerrard's Cross was reached by 10.30 a.m, and the water temperature had risen to 190° F.

Soon afterwards the rain started in earnest and from that time it never left us for long until the trip had been coMpleted. The roads were becoming greasy, but the chassis was remarkably steady and full use was made of its top speed of 54 m.p.h. whenever traffic conditions would allow. In spite of much weaving in and out of traffic it took 12 minutes to cover the four miles of main street through High Wycombe, but by the time the first hour was up we had covered 28 miles.

After a 15-minute halt on the Oxford by-pass to enable the photographer to catch up with the chassis, we continued at high speed for Cheltenham and at 11.45 a.m, we stopped for the first crew change. The radiator temperature had fallen to 176° F. and this proved to be its average figure when the chassis was driven at speeds above 50 m.p.h. on the open road. My namesake then took over the driving, and although he was unfamiliar with the vehicle, he experienced no difficulty in handling it through Gloucester, and the four miles of crowded streets were covered in 15 minutes.

Bristol was reached at 2 o'clock after a short break for a hot drink and food, and although we had encountered several sharp hills and spasmodic traffic, the 127 miles from Southall had taken only 3 hours 41+ minutes of running time, excluding the time spent in changing drivers and other " non-traffic " halts. A steep hill between Bristol and Bridgwater, near Diall Quarry, called for the use of third and fourth gears for nearly mile and this caused the water temperature to rise to 199° F. The Iowa half of the radiator had been blanked off to allow for the lack of shielding bodywork and it is possible that this blanking was too effective, thus explaining the sudden rise of temperature.

At Bridgwater I started my first spell of driving and before long was feeling at home with the chassis and confident that there were the speed and power available to encourage me to overtake most of the other traffic on the roads. The synchromesh gearbox made light work of gear-changing and faultless engagements were possible at all speeds, which contributed in no small way to swift acceleration. The brakes were smooth and effective in emergencies and only a light pedal pressure was required in normal circumstances.

Despite the big load on the front B10

axle, the steering was light and enabled the chassis to be kept on a line with no trace Of wander. Because of the low ratio gearing, plenty of energy was needed to swing the wheel round quickly when negotiating sharp corners, but at no time could it be classed as hard work.

From Bridgwater the road is fairly tortuous and narrow in parts, but no serious inclines were encountered until Porlock was reached, where we arrived at 4.40 p.m. As I had never driven up this hill before I let the works driver make the ascent. The climb starts in Porlock village and is over two miles long, with two sharp hairpin bends and an average gradient of 1 in 8, the severest section being 1 in 4. The first bend, about a third of the way up, was reached in second gear from a standing start at the bottom of the hill, but after 11 minutes in this gear the falling engine revolutions demanded low gear, which was used for 41 minutes. There was an abundance of power in low gear and no exhaust haze was seen during the climb. At the end of this run the water temperature was 199° F.

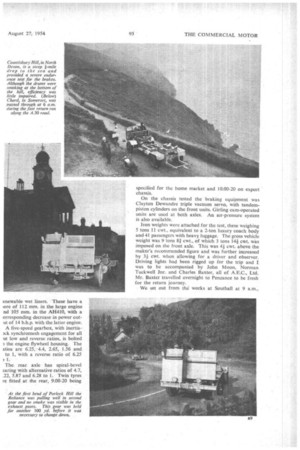

A strong wind blowing in from the sea made drivinE unpleasant along the cliffs between Porlock and Lynmouth but 40 m.p.h. was maintained until the descent of Countis. bury hill was made. This hill is mile long with an average gradient of 1 in 9, increasing to 1 in 44. at the steepest point I brought the chassis down in second gear, but it was neces. sary to hold the lever in position because a fault in the Iv) made the gear jump out of mesh even though the spec( was kept down by use of the brakes. The drums were smoking profusely by the time we had dropped intc Lynmouth, but the pedal travel had not increased sufficientl to cause any anxiety.

The hill leading up from Lynmouth to Lynton, althougt only -V mile long, has a general gradient of 1 in 6, with

1-in-4/ section, and a sharp left-hand bend near the begin fling. With third gear engaged I swept through Lynmoutl and up the hill and managed to get more than halfway in before having to change down to second and then to lo%, gear. Because I thought that low gear had not engage.

(which it had really), I stopped the chassis. The hand brak, held it easily and a smooth start was made in low gear, to th surprise of some holiday-makers who seemed to think tha we would have to drop back to a less severe section.

Several more steep hills were met before the road 'cyclic, out towards Barnstaple, and one of these necessitated th

use of second gear for two miles, during which period th radiator temperature rose to 182° F. Such climbs. naturall enough, took a toll of fuel and average speed, but lost tim was made up during the evening. The overall average spec was back above 30 m.p.h. by the time Newquay was reachec although a stop had been made to change drivers, have meal and refuel with 20 gallons. Penzance was reached at 11.45 p.m. and after picking up Baxter we carried straight on for Land's End. At 12.29 a.m., having travelled 354 rain-soaked miles in under 12 hours' running time, we stood at the end of England and made preparations for the return run.

Because of the time taken on the first section of the trial, the A30 road was followed for the greater part of the way back to the works and, being reasonably good, it provided the opportunity for some fast driving. There are no hills of any appreciable severity on this road and there was little traffic to impede our progress until we reached the outskirts of London, with the result that the 291 miles were covered at an average running speed of 32.25 m.p.h.

During the return run it was possible to form some idea of the high speeds that the Reliance would be able to sustain on a long main-road journey. The maximum speed in direct drive is 54 m.p.h. and for overseas work an overdrive would be an asset. Even in this country, despite the 30 m.p.h. limit, it should help to reduce fuel consumption, although its use would be restricted with a high rear-axle ratio.

At Southall the fuel tank was refilled to overflowing point and seven gallons were required. With the fuel that had been added during the run the total consumption was 47 gallons, this giving the excellent figure of 13.7 m.p.g. for 645 miles. The total running time was 20.88 hours, but, if included, traffic stops might reduce this time by 30 min.

Immediately after the fuel consumption had been checked

the chassis was taken out to the Western Avenue for shortdistance tests. Two consumption runs were made along a level return route of eight miles. The first was non-stop and a maximum of 30 m.p.h. was observed. The consumption rate was 19.1 m.p.g., and a second test over the same circuit, but making one stop per mile, produced a figure of 17.4 m.p.g., again not exceeding 30 m.p.h.

Acceleration figures confirmed what had seemed obvious during the previous 24 hours. Making quick changes through the gearbox, 40 m.p.h. was reached within 34.5 seconds from a standstill, the times taken to 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. being 8 seconds and 18 seconds respectively. The even spacing of the gear ratios ensures that high torque is available for each gear when changing up at maximum engine revolutions. Direct-drive acceleration was also most impressive, and the speed increased smoothly when accelerating from 10 m.p.h.

No adjustment had been made to the brakes since the run began, and they had been thoroughly used, not only when descending hills but also when road conditions demanded rapid slowing down. The figures of 30.5 ft. from 20 m.p.h. and 63 ft. from 30 m.p.h. tend to give a misleading impres • sion of the braking force available and could probably be improved upon when the brakes were properly adjusted. When the hand brake was applied from 20 m.p.h. the Tapley meter gave a reading of 36 per cent, efficiency.