INNER

Page 64

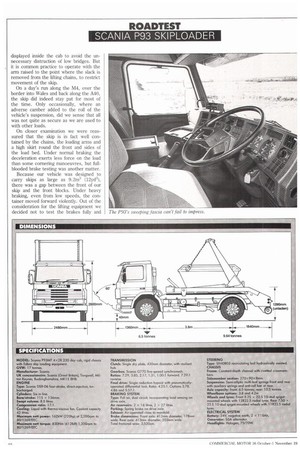

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THERE' MUCK...

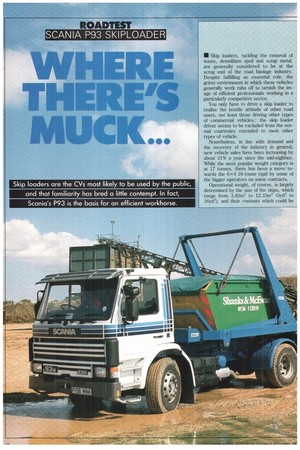

Skip loaders are the CVs most likely to be used by the public, and that familiarity has bred a little contempt. In fact, Scania's P93 is the basis for an efficient workhorse.

• Skip loaders, tackling the removal of waste, demolition spoil and scrap metal, are generally considered to be at the scrag end of the road haulage industry. Despite fulfilling an essential role, ' the grimy environment in which these vehicles generally work rubs off to tarnish the image of efficient professionals working in a particularly competitive sector.

You only have to drive a skip loader to realise the hostile attitude of other road users, not least those driving other types of commercial vehicles.: the skip loader driver seems to be excluded from the normal courtesies extended to most other types of vehicle.

Nonetheless, in line with demand and the recovery of the industry in general, new vehicle sales have been increasing by about 21% a year since the mid-eighties. While the most popular weight category is at 17 tonnes, there has been a move towards the 6x 4 24-tonne rigid by some of the bigger operators on some contracts.

Operational weight, of course, is largely determined by the size of the skips, which range from 3.82m3 to 12.23m3 (5yd3 to 16yd3), and their contents which could be anything from unwanted household goods to hardcore. Our test vehicle this week, a 17-tonner P93M Scalia based on a short (3.8m) wheelbase tipping chassis, is equipped withEdbro skip loading gear and a 4.6m5 (6y&) open-topped skip. Using hogging as a test load we cubed out before weighing out, leaving us about 0.75 tonnes short of the maximum weight allowed.

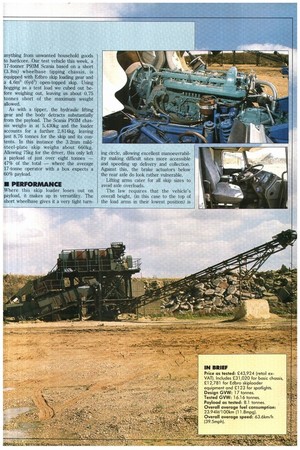

As with a tipper, the hydraulic lifting gear and the body detracts substantially from the payload. The Scania P93M chassis weighs in at 5,430kg and the loader accounts for a further 2,814kg, leaving just 8.76 tonnes for the skip and its contents. In this instance the 3.2mm mildsteel-plate skip weighs about 660kg. Allowing 75kg for the driver, this only left a payload of just over eight tonnes — 47% of the total — where the average 17-tonne operator with a box expects a 60% payload.

• PERFORMANCE

Where this skip loader loses out on payload, it makes up in versatility. The short wheelbase gives it a very tight turn ing circle, allowing excellent manoeuvrability making difficult sites more accessible and speeding up delivery and collection. Against this, the brake actuators below the rear axle do look rather vulnerable.

Lifting arms cater for all skip sizes to avoid axle overloads.

The law requires that the vehicle's overall height, (in this case to the top of the load arms in their lowest position) is displayed inside the cab to avoid the unnecessary distruction of low bridges. But it is common practice to operate with the arm raised to the point where the slack is removed from the lifting chains, to restrict movement of the skip.

On a day's run along the M4, over the border into Wales and back along the A40, the skip did indeed stay put for most of the time. Only occasionally, where an adverse camber added to the roll of the vehicle's suspension, did we sense that all was not quite as secure as we are used to with other loads.

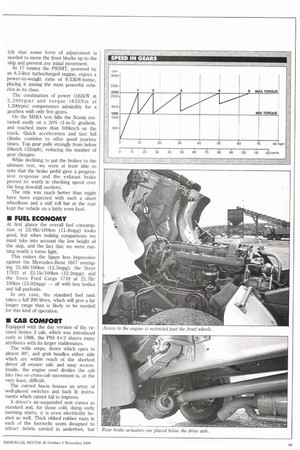

On closer examination we were reassured that the skip is in fact well contained by the chains, the loading arms and a high skirt round the front and sides of the load bed. Under normal braking the deceleration exerts less force on the load than some cornering manoeuvres, but fullblooded brake testing was another matter.

Because our vehicle was designed to carry skips as large as 9.2m3 (12yd3), there was a gap between the front of our skip and the front blocks. Under heavy braking, even from low speeds, the container moved forward violently. Out of the consideration for the lifting equipment we decided not to test the brakes fully and

felt that some form of adjustment is needed to move the front blocks up to the skip and prevent any initial movement.

At 17 tonnes the P93MT, powered by an 8.5-litre turbocharged engine, enjoys a power-to-weight ratio of 9.53kWhonne, placing it among the most powerful vehicles in its class.

The combination of power (162kW at 2,200rpm) and torque (835Nm at 1,200rpm) compensates admirably for a gearbox with only five gears.

On the MIRA test hills the Scania restarted easily on a 20% (1-in-5) gradient, and reached more than 100km/h on the track. Quick acceleration and fast hill climbs combine to offer good journey times. Top gear pulls strongly from below 50km/h (32mph), reducing the number of gear changes.

While declining to put the brakes to the ultimate test, we were at least able to note that the brake pedal gave a progressive response and the exhaust brake proved its worth in checking speed over the long downhill sections.

The ride was much better than might have been expected with such a short wheelbase and a stiff roll bar at the rear kept the vehicle on a fairly even keel.

• FUEL ECONOMY

At first glance the overall fuel consumption of 23.9lit/100km (11.8mpg) looks good, but when making comparisons we must take into account the low height of the skip, and the fact that we were running nearly a tonne light.

This makes the figure less impressive against the Mercedes-Benz 1617 averaging 22.6lit/100km (12.5mpg); the Steyr 17S21 at 23.11it/100km (12.2mpg); and the Iveco Ford Cargo 1718 at 21.71it/ 100Iun (13.02mpg) — all with box bodies and full payloads.

In any case, the standard fuel tank takes a full 200 litres, which will give a far longer range than is likely to be needed for this kind of operation.

• CAB COMFORT

Equipped with the day version of the revised Series 3 cab, which was introduced early in 1988, the P93 4 x 2 shares many attributes with its larger stablemates.

The wide steps, doors which open to almost 80°, and grab handles either side which are within reach of the shortest driver all ensure safe and easy access. Inside, the engine cowl divides the cab into two so cross-cab movement is, at the very least, difficult.

The curved fascia houses an array of well-placed switches and back lit instruments which cannot fail to impress.

A driver's air-suspended seat comes as standard and, for those cold, damp early morning starts, it is even electrically heated as well. Thick ribbed rubber mats in each of the footwells seem designed to attract debris carried in underfoot, but they are easily removed for cleaning.

A deep screen and large minors give good all-round visibility, but the external sun visor mounted across the top of the screen is of doubtful benefit and restricts the upwards visibility sometimes needed to read road signs or traffic signals.

Steering and foot controls are both light, and the stubby gear lever has a commendably short throw. The slightly off-line gate position hindered smooth selection, but this improved with practice.

At the rear of the cab, the Series 3 package includes a revised inlet stack, but retains a cyclonic pre-filter system preventing larger dust particles from clogging the main filter prematurely. Exhaust gasflow is used to draw any contamination clear of the inlet manifold: just what environmental implications this may have is anyone's guess.

The cab tilts through 60°, leaving the gear linkage undisturbed, but the proximity of the deep mudguards restrict access to the engine past the front wheels. As ever, daily servicing needs can be satisfied beneath the front grille.

• SUMMARY

High power and torque make light of the gearbox deficiencies, so quick if not so economical journey times are possible.

On site, the P93 4x2's short wheelbase makes it highly manoeuvrable, but the rear brake actuators could be located higher for better protection.

Scania's 3 Series cab provides a level of comfort that equals larger models in the range, together with a light and quiet environment.

All in all, anyone operating this level of equipment, priced in the region of 250,000, is clearly rebelling against the skip loader image.

0 by Bill Brock