THE HEAD HUNTERS

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

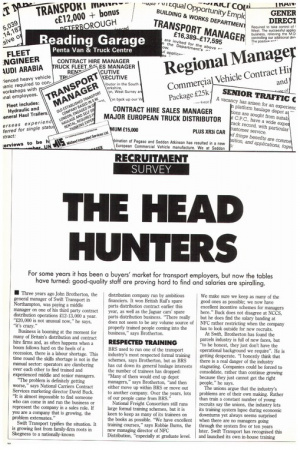

For some years it has been a buyers' market for transport employers, but now the tables have turned: good-quality staff are proving hard to find and salaries are spiralling.

• Three years ago John Brotherton, the general manager of Swift Transport in Northampton, was paying a middle manager on one of his third party contract distribution operations E12-13,000 a year. "£20,000 is not unusual now," he says, "it's crazy."

Business is booming at the moment for many of Britain's distribution and contract hire firms and, as often happens when a boom follows hard on the heels of a recession, there is a labour shortage. This time round the skills shortage is not in the manual sector: operators are clambering over each other to find trained and experienced middle and senior managers. "The problem is definitely getting worse," says National Carriers Contract Services marketing director David Buck. "It is almost impossible to find someone who can come in and run the business or represent the company in a sales role. If you are a company that is growing, the problem extenuates."

Swift Transport typifies the situation. It is growing fast from family-firm roots in Skegness to a nationally-known distribution company run by ambitious financiers. It won British Rail's spare parts distribution contract earlier this year, as well as the Jaguar cars' spare parts distribution business. "There really does not seem to be any volume source of properly trained people coming into the business," says Brotherton.

RESPECTED TRAINING

BRS used to run one of the transport industry's most respected formal training schemes, says Brotherton, but as BRS has cut down its general haulage interests the number of trainees has dropped: "Many of them would end up depot managers," says Brotherton, "and then either move up within BRS or move out to another company. Over the years, lots of our people came from RRS."

National Freight Consortium still runs large formal training schemes, but it is keen to keep as many of its trainees on the books as possible. "We have excellent training courses," says Robbie Burns, the new managing director of NFC Distribution, "especially at graduate level. We make sure we keep as many of the good ones as possible; we now have excellent incentive schemes for managers here." Buck does not disagree at NCCS, but he does find the salary banding at NFC rather restricting when the company has to look outside for new recruits.

At Swift, Brotherton has found the parcels industry is full of new faces, but "to be honest, they just don't have the operational background we require". He is getting desperate. "I honestly think that there is a real danger of the industry stagnating. Companies could be forced to consolidate, rather than continue growing because they just cannot get the right people," he says.

The unions argue that the industry's problems are of their own making. Rather than train a constant number of young recruits say the unions, the industry lets its training system lapse during economic downturns yet always seems surprised when there are no managers going through the system five or ten years later. Swift Transport has recognised this and launched its own in-house training courses for school-leavers, and it has taken on eight 18 year olds in the past six months: "Our best successes have definitely come to us straight from school or college," says Brotherton. "It has got to be the only way forward for us. Otherwise we are left with taking on 22 and 23 year olds out of the parcels business, paying them 210,000 or £11,000 and finding out that they are useless."

Brotherton likes practical training where possible: "I think that it is dangerous to develop schemes which are too academic," he says. He obviously worries about commercial nous being deadened. At NCCS, Buck sees things differently and he has just inaugurated a readership at the Polytechnic of Central London which has traditionally taken a keen interest in transport matters. "We're making the appointment now," he says. "Just one at this stage. They are rather expensive, but I think that it should also prove a very worthwhile experience, especially if we want to try and influence the academic side of things. We need more contact with the academic world to help create the kind of beast we need."

Buck is convinced that the distribution companies and the ar-demics should meet regularly to disc--,ss the changing face of the industry. "The whole face of this business is changing so fast at the moment There is a whole new world being thrown up — areas like logistics management would not have come into a transport operation in the past"

HEADHUNTERS

A lot of operators are having to resort to recruitment agencies and the so-called "headhunters" to get the managers they need. Chris Hayter, founder and managing director of a small but growing distribution company in Witney, Oxfordshire, used an agency to find two new managers earlier this year. "It was an expensive process," he says, and though he eventually found the people he needed, he would be wary of using an agency again.

Brotherton says: "The recruitment agencies are part of the problem. They wind people up to think that they are worth more than they are. People are registering en masse just to see what comes up. I think it is very unsettling; people here are being rung up all the time. We want them to stay here and have a future with us."

Several distribution companies are now asking interviewees if they know anyone else they can contact to fill up other empty jobs, and some are also offering their own employees rewards if they can put the company in touch with a suitable, and successful candidate..

STAFF TURNOVER

One distribution company we contacted has interviewed more than 100 people for its senior management team in the past six months alone_ Another, which did not wish to be identified, says that it has had nine to ten management posts unfilled at any one time for the past 12 months. Every time it tracks down a new member of staff, another one leaves.

United Transport personnel adviser Bill Horan says the company has had a "continuous problem" for the past year in trying to find decent contract hire sales staff. Wages have "spiralled", he says, and United Transport has found "some of our people whom we previously thought were just giving us a satisfactory performance have had to be reassessed. When we looked at what was on offer outside the company, we realised how low standards elsewhere were."

Every operator we contacted agreed that the transport industry is still selling itself short, especially within school, college and university careers offices. More effort is needed, says the end of term report. Students just are not told what the industry can offer and the rewards it can bring. Many criticised the Road Transport Industry Training Board for "not recognising the industry's problems quickly enough."

GRANT SYSTEM

The RTITB grant system is certainly reactive rather than pro-active, but there is very little it can do to persuade operators to train people if they do not want to do so. When times are hard, operators are certainly very backward at coming forward.

We also spoke to one of the industry's most prominent recruitment agencies. A spokesman for the company, which wanted to remain anonymous, said that last year a depot manager in south London was earning about 213,000. This year, he will earn 215,500. "I have recruited for three jobs in that area for these sort of sums this year," says the company spokesman. The agency also said: "Salaries are rising faster at the moment than they have done for the past 20 years, in real terms."

Recruitment agencies see a lack of proper career progression in the transport industry as one of the root causes of the current crisis. A decimated hire and reward sector in the past 10 to 15 years has not helped, and one recruitment agency we contacted was particularly critical of the own-account sector: "The mentality of the own-account sector is all wrong," said a spokesman. "A transport manager in charge of 90 drivers has traditionally earned less than a production line manager running 19 machine minders."

Accountants do not understand how to value transport operations, he said, because transport is not a physically accountable product.

D by Geoff Hadwick