A Light Electric

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

"Goes Through

the Hoop"

INTRODUCED almost a year ago, the Cleco Bijou batteryelectric has proved highly successful. The prototype, which has been on a baker's delivery round, covering 20 miles each day, has revealed no weaknesses in design, and it has not been necessary to make radical changes before going into full production with this model.

The Bijou, like others of the Clem range, is constructed on robust lines. Its. main. frame is formed from channel-section steel and is welded throughout. Mounted amidships, the It h.p. motor drives through a propeller shaft equipped with needleroller bearings to the double;eduction spiral-bevel gearing of the rear axle.

Cleco pattern controller gear incorporated in the electrical equipment comprises a pedal-operated quick-make-and-break contactor and auxiliary heavy duty mercury switches. A separate hand control, located by the side of the driver's seat, engages forward, reverse and neutral positions.

Exide Ironclad 24-cell batteries, housed at the centre and the rear of the chassis, can be serviced through floor traps in the body. They are of 161 amp.-hr capacity at the five-hour rating, and are contained in. five separate blocks.

A simple mechanical braking system is employed. The hand and foot brakes are interconnected and operate through cables to all four wheels. The internal expanding A32 brake units, with shoes 11 ins, wide, take effect on drums of 8-in. diameter.

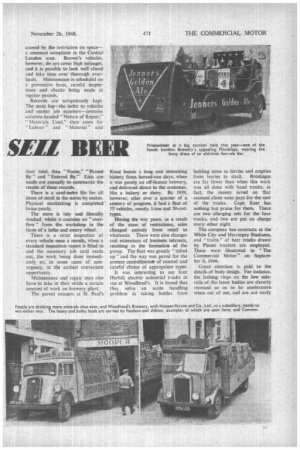

The light-alloy body, although of simple construction,, has attractive lines, the sweep of the cab panelling following the contours of the front wheels. Both sides of the cab are left open, and with an unimpeded gangway the driver can move across

the cab with ease and dismount from either side. The body side panels are attached to vertical steel angle pillars, welded at their bases to the frame structure.

Hinged doors are provided at the rear, and with no dividing panel between the cab and body, the loaves or other goods carried can be extracted from the front or rear. Ventilation louvres are pressed into the side and door panels.

Full Electrical .Equipment

Although produced at a competitive price, the quality of workmanship in the Bijou has not been stinted. The van has full electrical equipment, including lamps, horn, windscreen wiper and ampere-hour meter.

The test model was lent by West Wickham Garage, Ltd., the Southern distributor of the Cleco vehicles. The body of the van was equipped with racks to hold trays of bread and pastries, care having been taken in positioning them to ensure that the' floor traps could be easily removed.

When carrying bread the payload would be well below the capacity of the van, but to make the test comparable with others of the series a ballast load of 6 cwt. was employed. The van and load, plus the driver and myself, tipped the scales at slightly over l tons.

As no mileage recorder or speedometer is included in the equipment of the Bijou, I first drove over the course in a car to ascertain the distance between points and the total mileage. Having worked out the course, I started the continuousrunning test from the West Wickham Garage.

The Bijou was first driven through Eimers End to Beckenham, and, after turning at a roundabout, we retraced our course to the starting point. The complete circuit, which was 11 miles long, included steady inclines, which proved of value in determining the fall in power as the test continued.

The course had been planned to by-pass traffic lights and avoid congestion, and the complete test was made without stops. On level ground the Bijou appeared to have a normal speed Of 11-12 m.p.h., the speed being reduced to 7-8 m.p.h. when climbing the steeper inclines. The average speed for the first lap worked out to 11.5 m.p.h. and the second lap showed a reduction in speed of 0.5 m.p.h.

After turning at the roundabout during the fourth circuit the Bijou began to slow up on the gradients. At the end of 42 miles the fall in power became more noticeable, and caused by the restriction on space— a common complaint in the Central London area. Brewer's vehicles, however, do not cerver high mileages, and it is possible to took welt ahead and take time over thorough overhauls. Maintenance is scheduled on a preventive basis, careful inspections and checks being made at regular periods.

Records are scrupulously kept. The main log—the index to vehicles and master job numbers—contains columns headed "Nature of Repair," " Materials Used," then costs for " Labo ur " and " Material " and their total, then Nante,7 Passed By' and "Entered By."' Lists are made out annually to summarize the results of these records.

There is a card-index file for all items of stock he the stores by makes. Physical stocktaking is completed twice-yearly.

The store is tidy and. liberally stocked, whilst it contains an " overflow " from the workshop in the form of a lathe and emery wheel.

There is a strict inspection of every vehicle once a month, when a standard inspection report is filled in and the necessary job card made out, the work being done immediately or, in some cases of nonurgency, at the earliest convenient opportunity.

Maintenance and repair men also have to take in their stride a certain amount of work on brewery plant.

The parent concern at St. Paul's Road boasts a long and interesting history from horsed-van days, when it was purely an off-licence brewery, and delivered direct to the customer, like a bakery or dairy. By 1939, however, after over a quarter of a century of progress, it had a fleet of 55 vehicles. mostly 1-ton and 30-cwt. types.

During the war years, as a result of the mass of restrictions, sales changed entirely from retail to wholesale. There were also changes and extensions of business, interests, resulting in the formation of the group. The fleet was greatly "tidied up" and the way was paved for the present centralizatin of control and careful choice of appropriate types.

It was interesting to see four Harbilt electric industrial trucks in use at Woodhead's. It is found that they solve an acute handling problem in taking bottles from bottling stare to tarries. and empties from lorries to stack. Breakages are far fewer than when this work was an done with hand trucks; in fact, the money saved on that account alone soon pays for the cost of the trucks_ Capt. Kent has nothing but praise for them. There are two charging sets far the four trucks, and two are put on charge every other night.

The company has contracts at the White City and Harringay Stadiums, and "trains" of beer trucks drawn by Planet tractofs are employed. These were illustrated in "The Commercial Motor' on September 6, 1946, Great attention is paid to the details of body design. For instance, the lashing rings on the low siderails of the latest bodies are cleverly recessed so as to be unobtrusive when out of use, and are not easily damaged, Footholds, for access to the cab and body platform, are neatly protected by polished metal panels. Rear wheel-arches have covering panels, and rear number plates are recessed.

Any transport operator's " background " is every bit as important and interesting as his fleet, and the brewing of beer is particularly fascinating. It is made from malted barley, ground and mixed with water, or liquor as the brewer strangely calls it, to form an extract which is drawn off into coppers where hops are added. After boiling and cooling and other processes, the product is put into fermenting vessels where it receives the addition of yeast. Primary fermentation goes on for six to seven days, then the beer goes into tanks where it stays for at least a week, afterwards being chilled to 32 degrees F. for the purpose of carbonating before bottling.

Behind the Brewing Scene Brewing is a continuous process. Tbere may be anything from one brew a week to one a day, or more according to conditions. The normal working day is from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. In a rush period it is possible to produce and bottle beer within a week, but 17 to 20 days would be more normal.

Nineteen tons of the sparkling product leave the .brewery twice a day. All drivers have a morning and an afternoon journey, and the radius of operation is 25 miles, except for a weekly trip to Southend and an occasional one to Sidmout h. Deliveries are mostly to the group's own shops and licensed premises.

There is also a handsome delivery of wines each day. The company imports wine in casks, and bottles it on the premises. Wine cargoes are valued at about £1,000 a van-load, and the vehicles for this work are specially protected against theft and pilferage in addition to having steering locks fitted on the Fordsons.

"What does a 5-tanner actually carry?" I asked. "Approximately 450 gallons—that is, 1,800 quart bottles," said Capt. Kent. "A threetonner handles about 1,200 quarts."

There are return loads of empties on almost all journeys. Weights are then approximately halved in relation to bulk.

Loads of wine in the special vans go at about 45 dozen pints to the ton.

I learned more about loads on our next "hop," when we visited the South London Brewery at Southwark. There 1 was told that the 15-ton Atkinson takes 1,300

a4

dozen half-pints, in two-dozen cases. Even then, it is working within its capacity, as the weight of such a consignment is 141 tons. Carrying cask beer in 36-gallon barrels, it would take 33, but the weight would be only 71 tons.

Whereas Woodhead Brewery, generally speaking, covers t h e northern part of London, the South London Brewery, Ltd., supplies the south and west. It delivers some cask beer, but no wines. Much of its trade is for the export market, and the Atkinson and Maudslay are often to be seen nosing quietly eastward through the traffic, on their way to the London docks—the gateway to the markets of the world.

Our last port of call was at Hooper Struve and Co., Ltd., 26, Charlotte Street, London, W.1. From there, vehicles carry table-waters, fruit

squashes, tomato juice cocktails, cider, etc., all over Greater London and the Home Counties. From the Royal Spa, Brighton, other vehicles cover East Sussex, and even make sallies to Sidmouth, South Devon. All this company's vehicles are modern.

Like the transport employees of the breweries, Hooper Struve drivers and mates have to be specialists. A special problem is presented, in that " babies " and "splits "—two sizes smaller than half-pints—form part of the loads.

A mineral lorry may carry half again as many dozen bottles as a beer lorry. There is also a large syphon trade. Syphons, of course, are heavy for their size. They are also subjects for careful handling, and in very hot weather must be kept tarpaulin-covered

to prevent possible damage to the batteries the test was concluded after a mile farther had been covered. This test lasted for 31 hrs., and in calculating the effective capacity; of the battery this period has been used as the basis.

The batteries were changed during the lunch period, it being necessary to remove the ballast load to lift the floor traps covering the five battery units. A check on the specific gravity, of the battery electrolyte showed the replacement batteries to be fully charged, so the local delivery tests were started, using the same route as before.

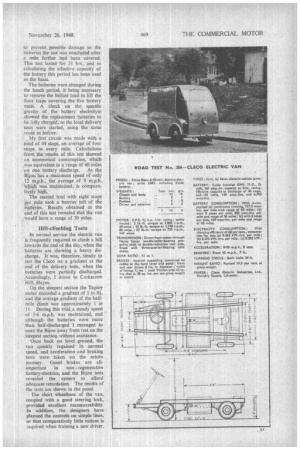

My first circuit was made with a total of 44 stops, an average of four stops to every mile. Calculations from the results of this test showed an economical consumption, which was equivalent to a range Of 40 miles on one battery discharge. As the Bijou has a maximum speed of only 12 m.p.h.. the average of 9 m.p.h. .was. maintained, is comparativelY".high. The second trial with eight stops Pr. mile took a heavier toll of the ba,tteries. Results obtained at the end of this test revealed that the van would have a range of 30 miles.

• Hilt-climbing Tests

In normal service the electric van is frequently required to climb a hill towards the end of the day, when the batteries are showing a heavy discharge. It was, therefore, timely to test the Cleco on a gradient at the end of the delivery tests, when the batteries were partially discharged. Accordingly, I drove to Corkscrew Hill, Hayes.

On the steepest section the Tapley meter recorded a gradient of 1 in 81, and the average gradient of the halfmile Climb was approximately 1 in 11. During this trial a steady speed of 5-6 m.p.h. was maintained, and although the batteries were more than half-discharged I managed to coax the Bijou away from rest on the steepest section without assistance.

Once back on level ground, the van quickly regained its normal • speed, and acceleration and braking tests were taken on the return journey. Good brakes are all important in non regenerative battery-electrics, and the Bijou tests revealed the system to afford adequate retardation. The results of the tests are shown in the panel.

The short wheelbase of the van, coupled with a good steering lock, provided excellent manceuvrability. In addition, the designers have planned the controls on simple lines, so that comparatively little tuition is required when training a new driver.