Current situation of electric vehicles

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Electricity Board feels they are arriving at a point where the economics make sense, writes Graham Montgomerie, but the triangle of range, speed and payload still has to be balanced

THE SERIES of demonstrations and lectures currently being organised as part of the "Drive Electric '82" programme are visible evidence of the efforts being made by the Electricity Board to promote electric vehicles.

Although there is usually a distinct lull in any conversation on electric vehicles whenever a 20-ton payload is mentioned, there is, nevertheless, a definite niche for the electric-powered light van.

Battery weight and limited range are two of the problems which have bedevilled the designer for some considerable time. Many light van operations, however, have a usage pattern which makes the limited range

of an electric vehicle less of a problem and Eastern Electricity is one such operator where this applies.

The Eastern area with headquarters at Wherstead, near Ipswich, extends from parts of North London up to Norfolk and includes Essex and Suffolk as well. Transport manager John Evans discussed with CM his experience of running electric vehicles within his 3,400-strong fleet. I had assumed that a certain degree of "political" pressure had been brought to bear upon the various Electricity Boards to run electric-powered vehicles, but John assured me that it was not quite like that.

"I run a transport fleet and I

have to provide the best, the most economical, vehicles for the job in hand," he said.

The Electricity Boards, he explained, feel there is a future in electric vehicles and with them arriving at a point where the economics make sense there is obviously a lot of internal encouragement for him to use electric traction.

"After all," said John, "our business is selling electricity and we should give a lead." He claimed that for certain applications (eg urban stop/start use) tremendous economy is possible with the present state-ofthe-art vehicles.

Eastern Electricity started off with the Enfield electric car which came into service in 1974. The Electricity Council has 40 of them still in service, of which nine are based at Wherstead. They are used as mobile test beds to experiment with various batteries and control systems and are effectively on free loan to Eastern staff after-hours on the condition that they are charged up again from the users' own domestic supply.

While visiting Wherstead I drove one of the Enfield cars and, although I have driven many electric commercial vehicles in the past, this was the first time I had tried a passenger car. One of the main criticisms levelled at electric power is based on adverse experience with milk floats; they are slow. While the Enfield did not break any records for the standing start quarter mile, neither did it become a mobile traffic jam. In the roads around Wherstead it was perfectly traffic compatible, with the only criticism being that pedestrians could not hear it coming.

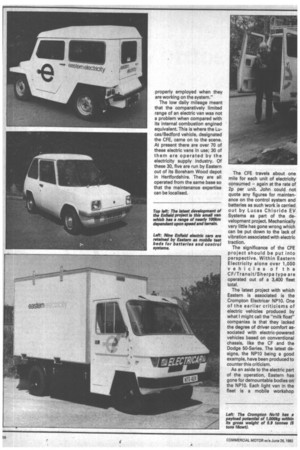

The latest development of the Enfield project is a small van which has a top speed on the level of 80km/h (50mph) and a range of 65 to 97km (40 to 60 miles) depending upon speed and gradient. This particular vehicle will do about three miles on one unit of electricity which at present night rates cost 2p.

This charging at night is another plus for the electric vehicle, according to the electricity authorities, who admittedly are not exactly without bias. There is tremendous generating capacity available to satisfy the needs of the daytime consumer (industry in particular) and so there is plenty of surplus capacity available at night for recharging electric vehicles for use during the following day.

The next step in Eastern's involvement was an analysis of the company's light van movements. The average daily distance covered was about 40km (25 miles) with an absolute maximum of 112km (70 miles). As John Evans explained: "to our paying customers this is good news. The drivers are our electricians who are only properly employed when they are working on the system."

The low daily mileage meant that the comparatively limited range of an electric van was not a problem when compared with its internal combustion engined equivalent. This is where the Lucas/Bedford vehicle, designated the CFE, came on to the scene. At present there are over 70 of these electric vans in use; 30 of them are operated by the electricity supply industry. Of these 30, five are run by Eastern out of its Boreham Wood depot in Hertfordshire. They are all operated from the same base so that the maintenance expertise can be localised. The CFE travels about one mile for each unit of electricity consumed — again at the rate of 2p per unit. John could not quote any figures for maintenance on the control system and batteries as such Work is carried out by Lucas Chloride EV Systems as part of the development project. Mechanically very little has gone wrong which can be put down to the lack of vibration associated with electric traction.

The significance of the CFE project should be put into perspective. Within Eastern Electricity alone over 1,000 vehicles of the CF/Transit/Sherpa type are operated out of a 3,400 fleet total.

The latest project with which Eastern is associated is the Crompton Electricar NP10. One of the earlier criticisms of electric vehicles produced by what I might call the "milk float" companies is that they lacked the degree of driver comfort associated with electric-powered vehicles based on conventional chassis, like the CF and the Dodge 50-Series. The latest designs, the NP10 being a good example, have been produced to counter this criticism.

As an aside to the electric part of the operation, Eastern has gone for demountable bodies on the NP10. Each light van in the fleet is a mobile workshop whose staff work as a team. Every time an integral van is booked for servicing, it takes quite a time to switch the tools and equipment to the spare vehicle. Having what amounts to a demountable workshop gets over this problem immediately. Another major advantage associated with demountable bodies is linked to the Electricity Board's appliance delivery system which uses 3.7m (12ft) long containers. These are usually trunked three at a time on a conventional flat platform trailer and are moved on to the local distribution rigids by means of hefty forklift trucks. Thus the NP10 demount system makes use of the lift-truck availability for swopping bodies and does not rely on landing legs and shunting chassis about the yard.

John Evans thinks the NP10 has got a great potential for people wanting a limited mileage service vehicle on an operation with a known daily pattern. Only one vehicle is in operation, but this is because of Crompton's limited initial production run as much as anything else.

The Crompton has a payload of 1,000kg within the gross weight of 5.9 tonnes (5 tones 16 cwt). This is the direct payload figure as opposed to a body/payload allowance and takes into account the demount system.

Running an electric vehicle is very much a question of balancing the "eternal triangle" of range, speed and payload. Increasing the range means more battery power which in turn means more tare weight and less payload — and so it goes on.

Eastern has so far concentrated its efforts on the light Vans and not committed itself to anything heavier. Having said that, John Evans is, nevertheless, watching the performance with interest of the Dodge 50-Series in service with Southern Electricity. These are being used as a large van for the joiners (electricity jargon for the men who work on the network in the streets) and for the maintenance of street lighting. John is very interested in the latter application as the low centre of gravity caused by the weight of the battery makes stabilisers unnecessary.

Even making allowance for inhouse bias, John Evans is happy about his electric vehicles. He would use more if they were available, and thereby hangs a tale. The Leylands, Bedfords and Dodges of this world are still just testing the water and thus production electric vehicles will tend to be produced in small batches only until there is a firm operator commitment.