Automated handling is the key in Scania's new factory

Page 52

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• With initial teething troubles overcome, the complex automated handling systems which are the heart of SAAB-Scania's newly completed truck factory at Scidertalje, near Stockholm, are now functioning smoothly and efficiently and making their planned contribution to the achievement of what Scania-Vabis claims is the lowest ratio of employees to output in any truck factory in Europe—or possibly the world.

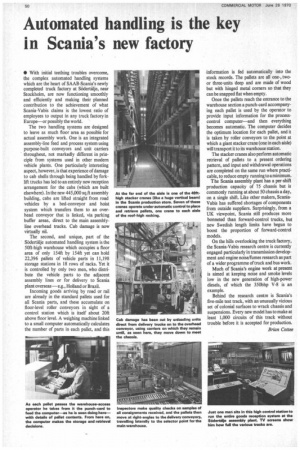

The two handling systems are designed to leave as much floor area as possible for actual assembly work. One is an integrated assembly-line feed and process system using purpose-built conveyors and unit carriers throughout, not markedly different in principle from systems used in other modern vehicle plants. One particularly interesting aspect, however, is that experience of damage to cab shells through being handled by forklift trucks has led to an entirely new reception arrangement for the cabs (which are built elsewhere). In the new 445,000 sq.ft assembly building, cabs are lifted straight from road vehicles by a bed-conveyor and hoist system which transfers them to an overhead conveyor that is linked, via parking buffer areas, direct to the main assemblyline overhead tracks. Cab damage is now virtually nil.

The second, and unique, part of the Sodertalje automated handling system is the 50ft-high warehouse which occupies a floor area of only 154ft by 154ft yet can hold 22,396 pallets of vehicle parts in 11,198 storage stations in 18 rows of racks. Yet it is controlled by only two men, who distribute the vehicle parts to the adjacent assembly lines or for delivery to Scania plant overseas—e.g., Holland or Brazil.

Incoming goods arriving by road or rail are already in the standard pallets used for all Scania parts, and these accumulate on floor-level roller conveyors in sight of a control station which is itself about 20ft above floor level. A weighing machine linked to a small computer automatically calculates the number of parts in each pallet, and this information is fed automatically into the stock records. The pallets are all one-, twoor three-units deep and are made of wood but with hinged metal corners so that they can be snapped fiat when empty.

Once the pallets reach the entrance to the warehouse section a punch-card accompanying each pallet is used by the operator to provide input information for the processcontrol computer—and then everything becomes automatic. The computer decides the optimum location for each pallet, and it is taken by roller conveyors to the point at which a giant stacker crane (one in each aisle) will transport it to its warehouse station.

The stacker cranes also perform automatic retrieval of pallets to a present ordering pattern, and input and withdrawal operations are completed on the same run where practicable, to reduce empty running to a minimum.

The Scania assembly plant has a per-shift production capacity of 75 chassis but is commonly running at about 50 chassis a day, on a single shift. Like other makers, ScaniaVabis has suffered shortages of components from outside suppliers. Surprisingly, from a UK viewpoint, Scania still produces more bonneted than forward-control trucks, but new Swedish length limits have begun to boost the proportion of forward-control models.

On the hills overlooking the truck factory, the Scania-Vabis research centre is currently engaged particularly in transmission development and engine noise/fumes research as part of a wider programme of truck and bus work.

Much of Scania's engine work at present is aimed at keeping noise and smoke levels low in the new generation of high-power diesels, of which the 350bhp V-8 is an example.

Behind the research centre is Scania's five-mile test track, with an unusually vicious set of colonial surfaces to wrack chassis and suspensions. Every new model has to make at least 1,000 circuits of this track without trouble before it is accepted for production.

Brian Cottee