DAF 7cwt

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

1 0/7 0

pick-up truck

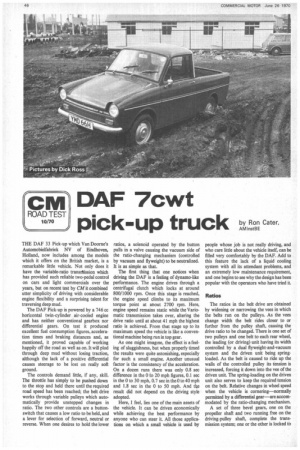

THE DAF 33 Pick-up which Van Doorne's Automobielfabriek NV of Eindhoven, Holland, now includes among the models which it offers on the British market, is a remarkable little vehicle. Not only does it have the variable-ratio transthission which has provided such reliable two-pedal control on cars and light commercials over the years, but on recent test by CM it combined utter simplicity of driving with considerable engine flexibility and a surprising talent for traversing deep mud.

The DAF Pick-up is powered by a 746 cc horizontal twin-cylinder air-cooled engine and has neither conventional gearbox nor differential gears. On test it produced excellent fuel consumption figures, acceleration times and braking distances and, as mentioned, it proved capable of working happily off the road as well as on. It will plod through deep mud without losing traction, although the lack of a positive differential causes steerage to be lost on really soft ground.

The controls demand little, if any, skill. The throttle has simply to be pushed down to the stop and held there until the required road speed has been reached; the belt drive works through variable pulleys which automatically provide unstepped changes in ratio. The two other controls are a buttonswitch that causes a low ratio to be held, and a lever for selection of forward, neutral or reverse. When one desires to hold the lower ratios, a solenoid operated by the button pulls in a valve causing the vacuum side of he ratio-changing mechanism (controlled by vacuum and flyweight) to be neutralized. It is as simple as that.

The first thing that one notices when driving the DAF is a feeling of dynamo-like performance. The engine drives through a centrifugal clutch which locks at around 800/1000 rpm. Once this stage is reached, the engine speed climbs to its maximum torque point at about 2700 rpm. Here, engine speed remains static while the Variomatic transmission takes over, altering the drive ratio until at about 41 mph the highest ratio is achieved. From that stage up to its maximum speed the vehicle is like a conventional machine being run in top gear.

As one might imagine, the effect is a feeling of sluggishness, but when properly timed the results were quite astonishing, especially for such a small engine. Another unusual factor is the consistency of the acceleration. On a dozen runs there was only 0.8 sec difference in the 0 to 20 mph figures, 0.1 sec in the 0 to 30 mph, 0.7 sec in the .0 to 40 mph and 1.8 sec in the 0 to 50 mph. And the result did not depend on the driving style adopted.

Here, I feel, lies one of the main assets of the vehicle. It can be driven economically while achieving the best performance by anyone who can steer it. All those applications on which a small vehicle is used by people whose job is not really driving, and who care little about the vehicle itself, can be filled very comfortably by the DAF. Add to this feature the lack of a liquid cooling system with all its attendant problems, and an extremely low maintenance requirement, and one begins to see why the design has been popular with the operators who have tried it.

Ratios

The ratios in the belt drive are obtained by widening or narrowing the vees in which the belts run on the pulleys. As the vees change width the belt rides closer to or further from the pulley shaft, causing the drive ratio to be changed. There is one set of two pulleys and one belt to each rear wheel, the leading (or driving) unit having its width controlled by a dual flyweight-and-vacuum system and the driven unit being springloaded. As the belt is caused to ride up the walls of the controlled pulley its tension is increased, forcing it down into the vee of the driven unit, The spring-loading on the driven unit also serves to keep the required tension on the belt. Relative changes in wheel speed when the vehicle is cornering—normally permitted by a differential gear—are accommodated by the ratio-changing mechanism.

A set of three bevel gears, one on the propeller shaft and two running free on the driving-pulley shaft, complete the transmission system; one or the other is locked to the shaft by a sliding dog to provide forward or reverse drive.

It always seems with a vehicle of small horsepower that one has to suffer poor fuel consumption when tackling a large number of stops and starts fully laden. The DAF was no exception, returning only 17.1 mpg at an average speed of 24 mph at four-stops-per mile laden. One has to push a small power unit fairly hard in order to get the road speed up to 30 mph between such stops and it is this that takes its toll of the fuel. In all the other fuel consumption tests the results jumped up way above 30 mpg, feaching a maximum of 51.7 mpg when running at a steady 30 mph unladen.

With drum brakes at all wheels the DAF produced quite staggering retardation results. On nearly every stop made the Tapley meter jumped right off the end of the scale, and all the wheels locked. Each time there was a slight tendency for the back end to slew into the kerb. due more to the road camber than any unbalance in the braking system. At a total stopping distance of 13ft 1 lin from 20 mph the results were very good, but the distances recorded from 30 mph were better than Ig, with constantly recorded distances of 28ft I lin on four separate crash stops, Ig of course being 30.2ft from 30 mph. The handbrake also produced above-average results, with Tapley meter readings averaging 49 per cent over a number of stops.

On each occasion that the rear wheels were locked up during a stop, the driving pulleys stopped in the high gear condition and on pulling away it took a few yards for the pulley attitude to change. It struck me that if one had to stop very quickly while climbing a gradient it would probably be impossible to move off again. When I put my theory to test on Bison Hill. that is just what happened and I had to roll backwards for a foot or so to readjust the belts.

One thing that one has to get used to when driving the DAF is to engage gear before starting the engine. If this is not done the centrifugal clutch-which is quite heavy -will spin on for some few moments, preventing the forward or reverse gears being engaged, without a very unhealthy gnashing of the dog-clutches.

The DAF carries a full 7 cwt payload quite easily, hut one must be careful how the load is imposed because spreading it evenly over the body floor results in the vehicle becoming tail-heavy when pronounced oversteer occurs. Shifting I cwt off the tail to a point just ahead of the rear axle line restores the handling qualities.

The pick-up version of the DAF 33 is provided with a very neat canvas tilt. When the vehicle is supplied new the tilt has to be fitted and the securing press-studs screwed into the bodywork. I tried fitting the tilt on the test vehicle and up to the point of actually drilling the bodywork for the press-stud screws this was quite a simple operation. The leading edge of the canvas is beaded and arranged to slide into a grooved aluminium moulding. This provides a neat draughtand-waterproof joint between the cab roof

and sides. A pair of steel hoops fits into tubes let into the body sides and these support the tilt at the rear and in the middle.

The trim in the cab is minimal in all respects except for the seats. This I consider to be a sensible way to spend money. But one of the things I certainly did not take kindly to was the way the front wheel arches protrude into the foot compartments, causing the driver in particular to adopt a rather uncomfortable attitude behind the wheel.

But the general finish on the vehicle is above average, with much use being made of stainless steel for the limited bright work.

Unusual by today's standard's is the 6 volt electrical system, which was rather reluctant to turn the engine over on one of the not-toocold mornings on which I had the vehicle on test-and it does not have a starting handle either.

The DAF 33 really needs to be sampled to obtain a true impression. For the layman driver, I would suggest that there has never been anything so simple and foolproof, and these are features which will also commend it to many professional operators.

As tested, the DAF 33 pick-up costs £569 10s.