Benchwise: lathe sense (19)

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

I HAVE described how the lathe can be used to face-up recovered vehicle parts as well as to turn round items, in each instance the work revolving against a stationary tool. There are, however, many tasks that must defeat the lathe unless certain additional items of equipment are obtained. Yet in vehicle repair the availability of these accessories can open up a new range of tasks. This extra repair facility can save time and money because often a part has to be replaced when a certain machining operation is impossible with the equipment available, either in the garage or locally.

In accident repair, particularly where engine damage is suffered, costs mount rapidly when such items as broken manifolds, thermostat housings, water pumps and filter castings are apparently damaged beyond repair unless there is a way of restoring certain flanges, slots, faces, etc. While usually it is the inability to revolve the item in the lathe that stops progress, if properly equipped the lathe can perform shaping and milling duties very efficiently indeed.

In these instances, however, the tool must revolve and the work remain stationary—here I am now referring to end milling and shaping cutters, tools that are driven by a suitable holder or arbor held in the mandrel taper. With the conventional lathe equipment there is a serious limitation to making full use of shaping or milling, as there is no provision to lift or lower the work.

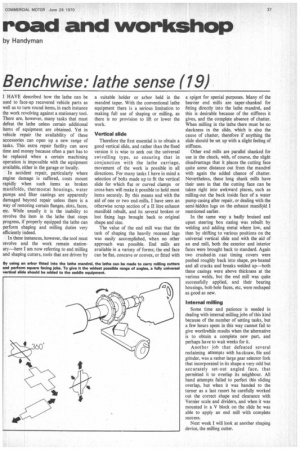

Vertical slide Therefore the first essential is to obtain a good vertical slide, and rather than the fixed version it is wise to seek out the universal swivelling type, so ensuring that in conjunction with the lathe carriage, movement of the work is possible in all directions. For many tasks I have in mind a selection of bolts made up to fit the vertical slide for which flat or curved clamps or cross-bars will make it possible to hold most items securely. By this means and with the aid of one or two end-mills, I have seen an otherwise scrap section of a II litre exhaust manifold rebuilt, and its several broken or lost fixing lugs brought back to original shape and size.

The value of the end mill was that the task of shaping the heavily recessed lugs was easily accomplished, when no other approach was possible. End mills are available in a variety of forms; the end face can be flat, concave or convex, or fitted with a spigot for special purposes. Many of the heavier end mills are taper-shanked for fitting directly into the lathe mandrel, and this is desirable because of the stiffness it gives, and the complete absence of chatter. When milling in the lathe there must be no slackness in the slide, which is also the cause of chatter, therefore if anything the slide should be set up with a slight feeling of stiffness.

Other end mills are parallel shanked for use in the chuck, with, of course, the slight disadvantage that it places the cutting face quite some distance out from the mandrel with again the added chance of chatter. Nevertheless, these long shank mills have their uses in that the cutting face can be taken right into awkward places, such as milling-out the back inside face of a water pump casing after repair, or dealing with the semi-hidden lugs on the exhaust manifold I mentioned earlier.

In the same way a badly bruised and upset steering box casing was rebuilt by welding and adding metal where low, and then by shifting to various positions on the universal vertical slide and with the aid of an end mill, both the exterior and interior faces were brought back to standard. Again two crushed-in cast timing covers were pushed roughly back into shape, pre-heated and all cracks and breaks welded up—both these casings were above thickness at the various welds, but the end mill was quite successfully applied, and their bearing housings, bolt-hole faces, etc, were reshaped as good as new.

Internal milling Some time and patience is needed in dealing with internal milling jobs of this kind because of the number of setting tasks, but a few hours spent in this way cannot fail to give worthwhile results when the alternative is to obtain a complete new part, and perhaps have to wait weeks for it.

Another job that defeated several reclaiming attempts with hacksaw, file and grinder, was a rather large gear selector fork that incorporated in its shape a very odd but accurately set-out angled face, that permitted it to overlap its neighbour. All hand attempts failed to perfect this sliding overlap, but when it was handed to the turner as a last resort he carefully worked Out the correct shape and clearance with Vernier scale and dividers, and when it was mounted in a V block on the slide he was able to apply an end mill with complete success.

Next week I will look at another shaping device, the milling cutter.