Distribution trends: Evaluating standards

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

of service by John Darker AMBIM NO ONE can work in transport for many days without hearing the phrase "service standards". From the smallest to the largest freight transport business — and it is no less true of buses and aircraft — the customer whose money sustains the business is concerned with service quality.

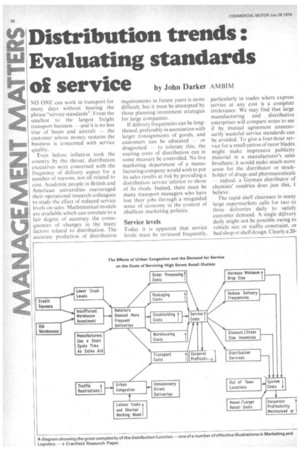

Even before inflation took the country by the throat, distribution ON executives were concerned with the frequency of delivery aspect for a number of reasons, not all related to cost. Academic people in British and American universities encouraged their operational research colleagues to study the effect of reduced service levels on sales. Mathematical models are available which can simulate to a fair degree of accuracy the consequences of changes in the many factors related to distribution. The accurate prediction of distribution -requirements in future years is more difficult, but it must be attempted by those planning investment strategies for large companies.

If delivery frequencies can be lengthened, preferably in association with larger Consignments of goods, and customers can be educated -or dragooned — to tolerate this, the soaring costs of distribution can in some measure be controlled. Np live marketing department of a manufacturing company would wish to put its sales results at risk by providinga distribution service inferior to those of Its rivals. Indeed, there must be many transport managers who have lost their jobs through a misguided sense of economy in the context of ebullient marketing policies.

Service levels

Today it is apparent that service levels must be reviewed frequently, particularly in trades where express service at any cost is a complete irrelevance. We may find that large manufacturing and distributive enterprises will compare notes to see if by mutual agreement unnecessarily 'wasteful service standards can be avoided. To give a four-hour service for a small carton of razor blades might make impressive publicity material in a manufacturer's sales brochure; it would make much more sense for the distributor or stockholder of drugs and pharmaceuticals — indeed, a German distributor of chemists' sundries does just this, I believe.

The rapid shelf clearance in many large supermarkets calls for two to three deliveries daily to satisfy customer demand. A single delivery daily might not be possible owing to vehicle size or traffic constraint, or bad shop or shelf design. Clearly a 20 ton or more load of mixed groceries would take time to 'off-load, check, and arrange on shelves, and there may be a case for doing the shelf display operation in a warehouse and mechanically transferring a "cartridge" encompassing an entire lorry load of pre-racked goods, to a suitably designed supermarket or hypermarket.

The service standard issue, it cannot be stressed too often, cannot be decided purely by varying the present distribution pattern — the "mix" of warehousing and road transport hardware. Majorchanges in shop design, location, marketing arrangements, vehicle design and mechaniml handling arrangements are called For. The technology of distribution must not stop with tail-lifts and caged )allets on wheels, however admirable hese are, within limits.

All this puts great onus on ransport managers and others concerned with The distribution function, to give thought to the total process. Instead of worshipping at the shrine of Physical Distribution Management as a rational philosophy for the 70s many more pilot test and experimental layouts of premises and vehicles, using scale models, would pay dividends.

With manpower costs forming such a high percentage of total delivery costs, the service standards of the previous century may compare more than favourably with what can be afforded not what is possible — today. In London, in the 1880s, there were about eight postal deliveries a day and some letters were delivered within the hour. Today, the Post Office would be grateful if some magic wand put a postbox at the end of every suburban drive. Newspaper vendors in country areas do not always deliver to the house, or even to a mailbox at the end of the drive.

In the ubiquitous "parcels" business, service standards today may be inferior to those of 40 years ago, as any old parcels expert will tell you. Before the days of motorized lorries horse-drawn wagon loads of chairs left High Wycombe nightly for early morning delivery in London. Transport operators do not find it difficult in 1974 to convince themselves that their customers are more concerned with regularity than speed., unless, by some happy chance, speed can be provided more cheaply. (The virtual ending of passenger liner traffic — other than for cruises — by air transport suggests that speed is sometimes cheaper than slowness. Passengers taking four or five days on an Atlantic crossing consumed much food, drink and costly personal service, contrastling markedly with the shorter flight time of a jet airliner. In the right context, the quicker road deliveries are made and the less warehousing and ancillary activities deployed, the lower the cost or is this too simple to be true?)

Parcels service

I recall writing an article in CM some eight years ago in which I urged the case for a 24-hour delivery service for parcels in this country. Obviously, such a service is possible. Equally obviously, it cannot easily or cheaply be provided by a national network involving a number' of transhipments. In theory, it ought to be possible, if better ways can be found to aggregate full-load trunk vehicle movements, possibly utilizing linked computer circuits of major manufacturers/distributors tied in to the traffic offices of.parcels operators.

Arguably, a case can he made for a 24-hour anywhere-to-anywhere service in this country for the better economic development of rural areas. "Greenfield" areas comprise something like 90 per cent of the land area of this country and you do not necessarily have to be an extreme nationalist to believe that light industries in country districts will never be able to compete on equal terms with the heavily industrialized areas so long as they are condemned — by the transport industry to third-rate service, or worse. The question for people living in remote rural areas is: "Why cannot the lush profits made by transport operators running services between the main conurbations subsidize the service levels we need to hoist our standards of living to something approaching that enjoyed in south-eastern Britain?"

Of course, a considerable number of operators, many of them new entrants to road haulage, have established themselves by providing express road services for things like computer tape with delivery between any points in the country within a few hours, utilizing air services as a speed-boost where necessary. The cost in manpower and vehicle usage is huge and the challenge to such operators is to expand their service coverage without eroding their present speed advantages and, hopefully, to do this at a much lower cost.

Service levels are not easily defined even by a large, sophisticated company with full management expertise. Bass Marketing's distribution director, Mr C. H. Scott, has said: "There is no doubt in my mind that we could give the best distribution service in the country, but at a cost. We have set our objectives in respect of customer service levels and we know what it costs us to provide this service."

He went on: "Customer service ... is the one factor which is almost impossible to quantify in respect to the cost of distribution. It could be that a small reduction in service would have a significant effect in reducing distribution costs, but it also follows that a reduction in distribution costs achieved without regard to customer service would have a very significant effect in reducing the number of customers. It is here that a fine balance must be achieved."

Cory Distribution's traumatic early experience led to the bolstering up of its management at all levels and this company today is extremely conscious of the need to provide a "tailored" service no better and no worse than its clients are prepared to pay for. Mr G. M. Audland, its sales consultant, told a conference of the National Materials Handling Centre; "It can cynically be said that some potential clients demand a much higher level of service that they expect to get hoping thereby to get the level of service that they really need. Bearing these points in mind, it is therefore of the greatest importance to a distribution firm to ensure that provided it has sold a level of service on a realistic basis, it ensures that it actually provides the service that it has sold."

To do this, Cory Distribution provides what is termed the "scattergraph" system at all depots. A form is completed daily showing at a glance whether or not orders are being delivered within the agreed number of days after their reception at the depot; it also shows whether orders are being held up and if so why. A "scattergraph" chart is maintained for each client and cumulatively filled up and this provides factual evidence in any emotional exchange between the distribution firm and its clients.

In a contract distribution service today you may find, as in the Cory Distribution network, the equivalent of the P.O.D..( Proof of Delivery) clerk, for long a familiar staff member in a parcels firm. Cory calls its offices "client service managers" and they are to be found at head office and at each depot. To provide the client service managers with up to date jnformation, the movement of all orders from receipt at the depot till completion of delivery are maintained in an Order Register, in fact a separate one for each client. The considerable administrative burden involved in maintaining these registers is amply recompensed by an improved relationship with client firms.