Foot note to the Heaton file

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Heatons have the distinction of being the principals in the longest running NIRC case

By lain Sherriff

MR MICHAEL FOOT is applying legalized euthanasia to the 1971 Industrial Relations Act, and burying the remains in the archives of the British Parliamentary system. The Act is going unmourned, it seems, and even Mr Edward Heath, its chief architect, shows little enthusiasm for reviving it when he returns to power.

To be buried alongside the Act is the National Industrial Relations Court which in its short history has surely been the cause of more fiery outbursts, silent demonstrations, and acrimony than any other similar institution. When I spoke to a Court official last week, in typical bureaucratic style but with a trace of regret in his voice, he said: "When the court goes, all of its papers will be buried with it." Among these papers will be the record of the NIRC's longest running case, and this dubious distinction falls to one of Britain's oldest family transport companies.

Heatons Transport (St Helens) Ltd was established before the turn of the century, and until 1971 had escaped the effects of militant trade union aetivity. Even during the General Strike in 1926 the trade unions allowed Mr Bob Heaton -now joint managing director -to carry on working, because he was an owner-driver carrying essential foodstuffs.

Almost half a century later, when the owner-driver had built his three-vehicle fleet up to 90 vehicles, 60 of them art ics, and offered ancillary services to his customers, he felt the full weight of Liverpool's militant dockers who are members of the Transport and General Workers' Union.

Blacking

The shop stewards at Liverpool in March 1972 instructed their members not to handle containers passing through the port consigned to or by Heatons. The reason for the blacking was because the company had refused to accede to a union demand that it should employ dock labour to pack and strip containers.

I wonder if the union would have .made the same demand, irrespective of whether they were passing through the port or to be used on domestic work, if Heatons had been based in St Albans rather than St Helens?

The passage of . the argument and counter-argument through the NIRC, the Court of Appeal, and the House of Lords, and the eventual judgement are now matters of history but not all of the arguments were heard in public.. Behind the scenes Bob Heaton and his son Bobby, the other joint managing director, regularly met union leaders Mr L. Lloyd and Mr A. T. Rafferty in Liverpool, in man to man discussions. Each side tried to get the other to understand its point of view. The company made what it believed to be an important concession by giving a guarantee that it would not enter into groupage work. The full import of the guarantee can be appreciated when we learn that Heatons have installed a container-bay costing "a . few thousand pounds" which would be "vastly under-utilized if the offer to the dockers were taken up and which undoubtedly meets the requirement of the Final Report of the Jones Aldington Committee to which Mr Lloyd is a signatory.

Changed relationships

From what was an extremely abrasive situation, relationships changed between the two parties over the years to one of almost understanding, and indeed, union officials like Mr Tony Rafferty at Liverpool described the Heatons to me as "very nice gentlemen".

Nevertheless these "very nice gentlemen" still find their containers blacked 'although the union has changed its position during the past three years. Whereas in the beginning they wanted to stuff and strip all of Heaton's container traffic, according to Mr Rafferty „their interests now are only in those of the company's containers which will at some point in their movement become. seaborne, and for this purpose even Irish ferry traffic is classified as seaborne.

It had been hoped that when the union officials met in June the Jones/ Aldington report. which was designed to clear up the anomalies in the British dock labour systems. would have been accepted and thus the Heaton problem would have been resolved. But once more the union rejected Heatons' arguments that their _warehouse space which was allocated to specific manufacturers for storage was an extension of the manufacturers premises. In Heatons case this applies to 150,000 sq ft of warehousing.

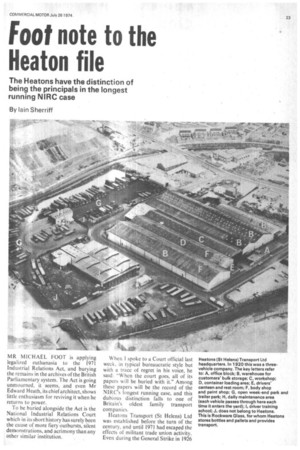

In this area, the company stores shrunk-wrapped pallets of bottles, electronic equipment. bags of powdered soap, chemicals and office furniture. Its customers include Plessey. Cadbury, Rockware Glass and Pilkington.

The bulk of the traffic is for domestic delivery but there are, of course, consignments destined for the export market, and this is where the "who does what" argument begins.

The dockers describe such consign

ments as groupage, Heatons contend that a container load of the same commodity consigned on behalf oithe same manufacturer is unit load traffic.

They asked the question: "How different is it for our men to make up the load into containers, from the manufacturers' men doing it?" This is a question which I understand has not yet been successfully answered by the dockers.

Standards met

Assuming that Heatons' container traffic is groupage the Heatons never will-then it is difficult to see why the dockers cannot accept that it complies. with the Jones-Aidington recommendations which say this about container groupage:

"Container groupage should to the greatest practicable extent be carried out by registered dock Workers, but if by other workers, then only under proper conditions of work, and all undertakings which handle groupage containers should satisfy themselves that these requirements have been met.".

No one has yet suggested that Heatons do not provide proper conditions of work. „ The dockers are not claiming that they should conic into Heatons' warehouses to pack the containers hut instead they are suggesting that Heatons should send a load along as loose cargo and have it packed into a container in the dock area. According to Mr Heaton this would add about 25 per cent to the cost and, of course, as any shipper and haulier will recognize, it adds to the danger of loss through damage or pilferage.

To service Heatons' 125,000 sq ft and 140 semi-trailers --there are almost two to every unit — the company requires only one foreman, three forklift drivers and one labourer for the warehouse. They see warehousing and container. packing as a natural development of any haulage business in this half of the 20th century, and by using 20th century methods, like pallets, mechanical handling and computers, they are not overmanned.

New development

Transport companies have long. moved from the days when they merely supplied vehicles to carry customer goods between two points, and Heatons most recent acquisition illustrates how the industry is developing generally.

After 18 months of negotiation, and in competition with other hauliers, they took over the transport fleet and distribution responsibilities of D. Matthews & Son Ltd who make office furniture in Lancashire. In this case they acqured Matthews's 35 chassis-cabs and drivers. Matthews retained the 70 swop .bodies which they . used with the vehicles. So that now .35 Heaton owned vehicles are engaged in either delivery direct from Matthews' factory to customer or conveying furniture from the factory to the warehouse in Matthews-owned bodies. In the Meantime the remaining bodies are being loaded at Matthews' premises. If instead of a swop body they loada container at the factory for export this will be accepted by the dockers, provided of course Heatons do not deliver it.

This type of operation clearly demonstrates the futility of the dockers' arguments. Containers packed by Matthews and carried on vehicles owned and operated by a haulage contractor are not subject to blacking except if that operator happens to be H eatons. 'there is little wonder then that the operator is confused by the dockers' attitude.

But it is not only the management who are confused. Heatons employees are not very sure how they would react to dock labour handling their traffic. Indeed, during the early part of the dispute, the drivers at Heatons '(who, like the dockers, are members of the T(IWU) claimed that their brother trade unionists at the docks were stabbing them in the back. I spoke to one or two of the men at St Helens who, for fear of some reaction, spoke "off the record". None of them could. find any justification for the dockers' action and without exception they supported their boss in his fight. Most of the company's 170 employees are long-service men; the oldest has been there since 1930.

The 14eatons have offered to waive their £10,000 compensation claim against the union if they can reach an agreement on a national negotiation procedure_ This is a further indication that the company did not set out on a union-bashing expedition. The company feared that the union's activity would interfere with its profitability and I understand that in the early stages the loss of export/ import traffic gave cause for concern. In the meantime, however, due to what Mr Heaton snr, described as the loyalty of customers and staff, domestic traffic has been built up and it is now less important to Heatons that they should be sending traffic through Liverpool docks. What must give the industry cause for concern is that someone must be handling this traffic, and that someone could very soon become the next victim , of the dockers' militancy. This is now much more of a reality with last week's proposals from Mr Foot to extend the Dock Labour Scheme to non-dock-scheme ports.

The whole situation still revolves round the definition of groupage and whether or not a warehouse is an extension of manufacturers' premises.

Now that Michael Foot has achieved his avowed -intent of disposing of the NIRC perhaps he will find time to go up to Liverpool and sort out the who-doeswhat :dispute. Where Sir John Donaldson, the House of Lords, Jack Jones, and Lord Aldington have apparently failed, can the Employment Secretary succeed? If he can, he will earn the admiration of the haulage industry and the grateful thanks of Bob and Bobby Heaton.

Or would Mr Foot rather please his Party's left wing and the dockers?