NFC

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 51

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

how much of a challenge?

THE PROBABILITY that Sir Reginald Wilson will become chairman of the National Freight Corporation will surprise no one who has followed the stages by which Mrs. Castle's brainchild has progressed from a BTC-style monolith to a commercially directed, company-structured organization. The Minister's speeches at the 1967 Labour Party Conference and in the Transport Bill debate reveal how completely she has set her face against the sort of monopolistic money-loser which the TUC, for one, has been pressing for.

This may seem small comfort for the private road operator, who finds it difficult to look dispassionately at an organization with borrowing powers exceeding 1200m. (to swallow him up?), and the right to carry and store virtually anything, anywhere at any time. Especially when the plans for its structure and its future are given in contentious Government documents that simultaneously spell out the means by which NFC and British Railways will be able to grab own-account and haulage traffic and put them on to rail. And when the present Government's attitude to a mixed economy comes through in such phrases as "the NFC's duty will be to expand vigorously as a commercial enterprise and it will seek every opportunity, as the Transport Holding Company has done, to acquire new businesses by voluntary agreement and to integrate them with its functional subsidiaries".

But it could have been much worse. The creation of a ETC sort of structure would have given yet another lease of life—if that is the right word—to the uneconomic and unenterprising conditions under which British Railways has staggered along for year after dreary year. And the brighter side of State transport—the Transport Holding Company—would have been swallowed, together with its profits and its carefully nourished links with non-State road haulage.

For the faithful of the Left, the White Paper has to spell out the reasons why such a course is wrong: energies required in pushing the progress of such a Commission would be dissipated in trying to solve those long-standing railway problems. And the White Paper admits that the BTC was a body with a size and range of responsibilities which made it difficult in practice to get to grips with the basic problems of re-organization "to achieve road /rail integration". So we are, thank goodness, promised something very different; something very much on the lines of the THC, and therefore something which the current Holding Company chiefs find acceptable to work towards, even though it means the end of the highly successful and highly profitable THC.

The Transport Bill and the freight White Paper spell out in some detail the future of State transport in Britain for many years—probably regardless of political changes, whatever the Opposition may feel or say at this moment. And the inevitable conclusion is that the NFC will dominate British goods transport in a way that the THC, for all its size, has never really done.

Paragraph 11 of the White Paper states: "The Government intends that the publicly owned freight services shall operate on strictly commercial lines. But, if this is to be done, and seen to be done, it is important that the various freight activities should be broken down for operating purposes into units which make functional sense and which can be held financially accountable for the work that they do. Only in this way will it be possible to cost their work precisely and openly, to eliminate undesirable crosssubsidization and to achieve real economies by integrating like with like".

This is the crucial issue. Although the 1962 Transport Act produced by Ernest Marples laid the guide lines for a successfully commercial State road haulage organization, neither Beeching pills nor Raymond tourniquets have stopped the railways' bleeding, nor stopped it increasing to a rate of over £150m. a year. Quite apart from the National effects of such a dispiriting performance, both publicly and privately owned road haulage are forced to compete with a railway system which not only indulges in cross-subsidy between one traffic and another but is also kept alive by a committed Government on the basis of preservation and a general subsidy.

Commercial approach

Now we have the picture of a Left Wing Minister in a Socialist Government laying down a more commercial approach—based on the doctrines , which the leaders of the Transport Holding Company have so successfully translated into practice over the past few years. There is indeed a Wilsonian ring (and we do not mean Harold) in the phrase "into units which make functional sense and Which can be held financially accountable". Look at the THC; look at the structure of Northern Ireland Carriers, in which managing director Trevor Thornton was very much influenced by the THC ideas. In NIC one can see, in a small way, the probable structure of the new National Freight Corporation. Not unlike the Transport Holding Company but arranged much more strictly in functional groups, in that parcels go with parcels and tankers go with tankers and so on.

The Freight White Paper and the immediately preceding one on

railway policy leave little doubt that the railways are going to suffer the most savage reorganization of all in the coming few years. The approach will be: separate each section and examine its financial standing; if it is socially necessary, subsidize it. If it is not sociably justifiable, identify the "wholesale" rail-originating bulk or similar traffic which can (a) be made profitable though retained in railway hands or (b) is hopelessly unprofitable and must be shed. Then any traffic which can more profitably or more suitably be handled as road-originating traffic will be hived off to the National Freight Corporation as yet another division of that organization's activities.

Already this is being done with the two most obviously road-originating traffics: the Freightliner services and the sundries traffic. There has been an outcry, particularly by the Tories, that taking the Freightliners away from the railways removes one of their few hopes of profitability. One can see the logic that prompts this point of view but the critics perhaps fail ro realize that the railways have a poor chance of maximizing this investment, and that unless there is separate and very clear accounting, there is always the danger that liner trains will be, deliberately or not, cross-subsidized.

This has long been a complaint of the private haulier, and it is a view which is certainly shared by the THC. The safest way of ensuring separate and patently honest accountability is to put the operation at least partly under the control of other than railway interests. This is what the Government has decided to do, by setting up the Freightliner Company as a subsidiary of the NFC.

Similarly with the sundries operations. Although British Railways' sundries services occasionally carry the odd heavy consignment, their nominal limit is 1 ton per shipment; but this type of business is one that most of the United States railways gave up a long time ago as being quite unsuitable. So into the NFC, too, go the railways' sundries services, after• a development period in the Joint Parcels Organization. Another transfer to NFC is the British Rail cartage fleet whose standardization with British Road Services vehicles and operations is being discussed in the new Joint Freight Organization.

In fact, at every step the National Freight Corporation looks like a re-creation of the Transport Holding Company. But with three big differences. It will be enormously larger—with about 33,000 vehicles. It will be committed to making the most extensive possible use of rail and will have the Minister of Transport in a position to prod it to do this, especially on the advice of her advisory Freight Integration Council. And it will no longer be permitted to take part in mixed ownership of subsidiaries.

The THC has very successfully allowed private minority holdings to be retained in some of the companies which it has acquired and has benefited from the enthusiasm and expertise which those holdings often represented. It is a pity that this must now go by the board (in fact the practice has been prohibited by the Minister since last April) and although one can see some organizational sense in this step it is really a response to persistent pressure by the trade unions.

And, of course, another important difference between THC and NFC will be the much more functional division of the operating companies; but this would almost certainly have happened over the next few years even with die THC itself.

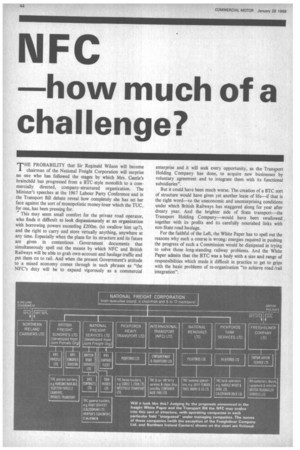

Vesting day for the NFC is set for January 1 1969, and the accompanying organization chart gives some idea of how the structure of British State transport might appear at that time, or soon after. It will be matched on, the passenger side by the 25,000 buses and coaches operated by the National Bus Co, and the Scottish Transport Group.

But whereas the publicly owned National Bus Co., Scottish Group and PTAs will between them dominate the road passenger transport industry to the extent of operating, say, 90 per cent of all stage carriage services, the 33,000 road vehicles of the NFC will represent only just over 5 per cent numerically of all goods vehicles over 30cwt unladen—that is, those coming within the scope of quality and quantity licensing. These number 600,000 vehicles, including own-account. But the NFC fleet is a sizeable one by any standards, and comprises around 15 per cent of professional haulage vehicles.

This State fleet will be in an exceptionally strong position, especially with its new powers. It is not only large, well dispersed and based on a national network of depots and workshops but is also in relatively good condition. Even more important operationally is the fact that it will now be integrated with the Freightliner system. So instead of being in only a slightly more favourable position than private hauliers in the matter of supplying collection and delivery vehicles for railway containers, the State road fleet will virtually be running the service. And with a directive to get as much traffic as possible on to rail, the NFC will be only too glad to have terminal c. and d. work to occupy the vehicles and drivers taken off other services.

In these circumstances it seems probable that the private haulier looking for c. and d. work will have a very thin time. A haulier who fears that his business may be hit by the new legislation and who wishes to survive as part of the new road-rail pattern should do better by putting a high proportion of his own customers' traffic on to rail for the trunk and not relying on c. and d. under contract to the railways as a major part of his future business. Always providing that BR and NFC behave ethically and don't then steal the haulier's traffic from him.

Well advanced

There are few who are big enough to contemplate doing the Tartan Arrow type of operation using their own rail depots, but there is still time to form area groups to provide container traffic originating from road customers. Manchester hauliers are already well advanced with such schemes, and we know that RHA members in the Glasgow and London areas have had plans of this sort for many months. They would be well advised to go ahead with them and, indeed, one hopes that the Road Haulage Association is ready and able to give its members the most comprehensive and far-sighted professional advice on how to meet the new challenge which the NFC, and other aspects of the Transport Bill, present.

The time-scale of all the proposals must be kept in mind when considering the effects of them, and whereas target vesting day for the NFC is January 1 1969, the Government "intends to be satisfied that the new Freightliner service has proved itself in practice before quantity licensing is introduced". And this is very unlikely to be in 1969.

To read the White Papers and the Transport Bill is to realize how little confidence the Government places in the commercial abilities of British Railways. Virtually every growth traffic is being taken out of their hands so far as the marketing and day-to-day control is concerned. Not only are the NFC and Freighdiner Co. to receive a large slice of rail freight, but the PTAs, when they are set up, will be responsible for taking over the local rail passenger services.

How does the THC see things? Naturally it does not corntemplate its own liquidation with enthusiasm or pleasure but the fact that, in general principles, the NFC appears to differ so little from the THC, paves the way for a smooth transition. With Sir Reginald Wilson as chairman of the organizing committee, this seems assured.

Point of disagreement.

One serious point of disagreement is likely to arise over the same_ matters that have aroused such a storm from private road operators, namely the quantity licensing and haulage taxation proposals. For, while the THC has welcomed the quality licensing plans, it has remained significantly silent on the two more controversial measures and it is fair to assume that this silence indicates disapproval.

Of course, in its passage through Parliament in the present economic circumstances, the Transport Bill may lose some of its present shape, but Mrs Castle is a determined Minister and it would be surprising to see any major changes made in the plans for the National Freight Corporation.

Rationalization of the functional groupings of the THC freight activities is seen as "precursor to integration with the corresponding rail activities". Whether this means that the regional control vested in such groups as Tayforth will completely disappear is not yet clear, but certainly it seems that the functional separation will take priority over any area grouping.

So we shall probably see, for example, British Road Services Ltd. absorbing more completely such THC subsidiaries as Corringdon Ltd. and Morton's (Coventry), while it may also become more directly responsible for such haulage constituents of Tayforth as Caledonian Road Services (Contracts) Ltd., D. McKinnon (Transport) Ltd., Road Services (Caledonian) Ltd., and Road Services (Forth) Ltd.

New momentum

The first stage of rationalization, which is already under way in the parcels sphere, will be given new momentum so that James Express Carriers, N. Francis and Co., Wm. Cooper and Sons, Hanson Haulage, Scottish Parcel Carriers and other companies of a similar nature are likely to BRS Parcels Ltd. under the general umbrella of a company with some such name as the Freight Sundries Co. Into this group will go the British Railways sundries division—but final integration of road and rail parcels and sundries is still quite a long way off. Not only are trade union problems, and the prospects of a fairly costly wage assimilation policy, reasons for delay, but the Government's decision to provide a subsidy to the NFC for the expected loss, or part of the loss, on this traffic over the first five years under NFC direction means that this side of the business will have to be kept separately accountable. This also means that the £1.1m. profit which BRS Parcels Ltd. and its subsidiaries made in 1966, for example, will not be unidentifiably swallowed up in an inherited rail service that managed to lose £25m. in the same year by spending £50m.

Uneconomic But the fact must be faced that a large part of the sundries traffic is hopelessly uneconomic. It is the sort of business in which the more-one carries the more one loses; and the answer to that is to carry less. With a healthy and growing parcels businesf of its own, and good links with private parcels and smalls carriers, the NFC will be in a better position to make such a harsh decision on a commercial basis than the railways have ever seemed to be.

Against this, the reorganization planned—and partly achieved —by BR Sundries Division looks like slashing some of the losses. It is now based on 500 key warehouses—perhaps the nucleus of that municipal warehouse delivery plan about which several kites have lately been flown?

As the chart indicates, alongside the general haulage and parcels groups we may expect to see directing companies for bulk liquid transport, removals, heavy haulage, and international and shipping services, with the relevant companies separated out from their present positions in BRS, Pickfords and Tayforth groupings. There will also be a major subsidiary in the form of the Freightliner Company, which will absorb Tartan Arrow as well, while the 50 per cent holding in Northern Ireland Carriers is another major interest retained.

In some cases the groupings will be complicated by the fact that, despite its present policy of complete control, THC does not have 100 per cent ownership of all the companies in which it has interests. Presumably the remaining private interest in Tayforth Ltd. can be bought out by agreement, but it will be interesting to see what eventually happens in respect of the Leyland Group's holdings of 25 per cent in Bristol Commercial Vehicles Ltd, and Eastern Coach Works Ltd., for part of the payment for these interests was a reciprocal holding by the THC of 28.8 per cent in Park Royal Vehicles Ltd. But this is not a problem for the NFC, because Bristol and ECW will become part of the National Bus Co. It is likely that the two goods vehicle bodybuilding concerns, Spcn Coachbuilders Ltd. and Star Bodies (BRS) Ltd., will be absorbed into the general haulage company, The NFC will, even without expansion, be responsible for an enormous amount of traffic. Although British Railways, after the initial reorganization, will still be left with a potential 200m. tons a year of train-load and wagon-load traffic, the NFC will assume responsibility not only for Freightliners and for the vast sundries tonnage, but also for the proportion of general merchandise rail traffic which can be more effectively handled on a door-to-door basis. Groupage depots (and perhaps mtinicpal warehouses?) are obviously going to be one of the keys to this reorganization of merchandise traffic, because the Government foresees the NFC providing a "modern and efficient through-service, using road for collection and delivery, with traffic grouped at the terminals for trunk movement in bulk by rail, thus exploiting to the full the new rail Freightliner services for the carriage of traffic in containers".

This sort of groupage work will presumably be the responsibility of the Freightliner Company in which British Railways will retain a 49 per cent interest and will have an appropriate number of seats on the board. It will also get a proportionate share of the profits. But although British Railways will be able to nominate members for seats on the board of the Freightliner Company, it will be the NFC that appoints the board members.

Reassurance Reassurance to private hauliers comes in the statement of intent which reads as follows: "The Freightliner Company will have commercial freedom in determining its charging policy. It will normally employ a standard charging system available to all but will be free in the usual way to incorporate discounts for quantity, regularity, etc. As well as selling through-services direct to the consignor it will offer a transport advisory and contracts service to industry. It will also sell space on the Freightliners to other hauliers, The Freightliner terminals will continue to be open to the private haulier and to the own-account operator without discrimination either as to the charges levied or the services provided".

Which sounds fine until you ponder on who will stand to benefit most by the discounts; why, the NFC of course, who therefore may get a rates advantage in attracting traffic.

The Railways Board will negotiate a commercial charge for providing and hauling the Freightliner trains in order to "cover its long-term avoidable costs and secure an adequate contribution towards its indirect costs, including track costs".

And as well as the levy for hauling the trains, the railways will, of course, have their share in the profits. In these circumstances, and with a declaration of intent to keep separate and clear accounts for Freightliner operation, it will be interesting to see what will happen to Freightliner rates.

The terms of reference given to the NFC emphasize its general similarity to the THC. The role of the NFC board will be to set the framework within which its various subsidiaries will operate, rather than to manage them, while "there will also be arrangements at national level to permit co-ordination with other operators". The NFC's duty will be to "expand vigorously as a commercial enterprise", but some may think its ability to do this will depend on political as well as commercial factors.

Commercial performance As to its commercial performance, there is an aspect of the organization which may appear to limit this, namely the Government's stated aim of "securing closer association of the workers with the processes of governing and organizing undertakings of this kind. The most effective ways of doing this are matters for discussion between the NFC and the trade unions concerned". Does Mrs. Castle cherish dreams of worker-management?

But we should not let all the red flags in what are, after all, fundamentally political documents obscure the commercial realities which lie behind the phrasing.

The NFC is quite clearly stated to be a "free-standing corporation responsible to the Minister", but it is significant that, in addition to the normal powers which a Minister has in respect of nationalized industries—on such matters as investment and finance—Mrs Castle has now taken extra powers which enable her to give specific directions to the NFC and BRB on "matters which appear to her to require such directions and which arise from the recommendations made to her by the FIC".

The FIC is the Freight Integration Council, a watchdog body which will review and report to the Minister on the application of the policy for freight integration. It will also act as arbiter when BRB and NFC fail to agree. This will be a small, part-time, non-executive body comprising the chairman of the British Railways Board, the chairman of the National Freight Corporation, representatives from the trade unions representing road and rail workers and a few independent members, under an independent chairman.

So there it is—or soon will be. A vast and enormously powerful State transport organization with about 33,000 vehicles, plus rail traffic to organize and shipping services to run.