TAKEN ON

Page 60

Page 62

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BOARD

Most operators have tales to tell of inaccurate weighbridges, and an on-board weighing system could be the answer.

Despite strenuous representations by the Road Haulage Association and others, "due diligence" remains a somewhat ineffectual defence against overloading. Magistrates continue to impose fines of £2,000-plu5 where trucks are found to be a tonne or more overweight. Individual axle overloading, within legally allowable all-up weights, is now also treated with far less lenience by traffic courts.

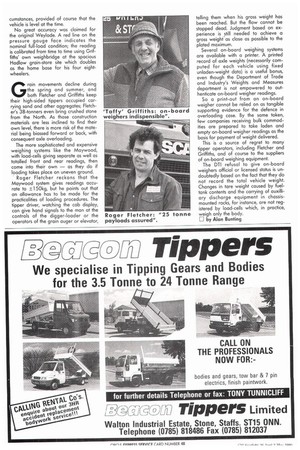

An on-board weighing system which can avoid such unwitting legal infringements need not take long to pay for itself, when productivity as well as avoidance of legal penalties are taken into account. Tipper haulier Roger Fletcher of Culverstone, Kent, whose main traffic is grain and animal feed, says he winced at the cost of around £3,000 to fit each of his three Scania-Wilcox 38-tonne ortic bulkers with a Maywood On-Board weight indicator system. The four loadcells, the box of electronic gadgetry and the in-cab control and liquid-crystal display unit simply do not look like £3,000 worth of kit, he says, even when allowance is made for installation.

Fletcher says his motivation for investing in the equipment was two-fold. Without it, he faced the possibility of lost earning capacity. Many smaller farms have no weighbridge, and even at a big grain store, he points out, the shovel loader may or may not have load-cell weighers on its lifting arms. Erring on the side of caution to avoid being caught overloading was an unacceptable erosion of vehicle productivity.

Even where a site does have a weighbridge, it is never possible to use it to monitor vehicle or axle weights while loading is in progress. Inordinate time can be wasted in repeated check weighing. Going to the weighbridge — sometimes a kilometre or more away — and then returning either to tip off the surplus or get a little more put on can reduce the number of trips possible in a day, typically from five to four.

This assessment was made by another tipping haulier CM spoke to in Kent: Llewellyn Griffiths, known to everyone as 'Taffy', despite having spent all his life in and around Hadlow, near Tonbridge. Griffiths runs four Eagle 265-powered rigid eight-wheelers: three Leyland Constructors and one venerable ERF. Two of the Leylands have Precision Loads weighers, simpler forerunners to today's Maywood equipment.

The third and oldest (A-registered) Constructor was the first to be equipped with a weight indicator — the original Weylode device which simply monitors tipping ram pressure when the body is raised off its runners.

It is not difficult to see why Fletcher wants to exploit the full payload capacity of his 38-tonners. He started in business five years ago, driving a Scania 112 with a Wilcox trailer. He was previously a contracted owner-driver

with ARC, with whom he still enjoys a close relationship — ARC's Borough Green depot is Fletcher's nominated operating centre.

That original outfit would carry just 25 tonnes — four loads meant 100 tonnes, which made for neat and convenient administration by all four parties concerned in grain movements: the farmer, the flour miller, the agricultural merchant and the haulier. When Fletcher came to expand his operation he went for Scania's more powerful vee-eight-engined 143. The bigger, gutsier 336kW (450hp) engine brings more durability and, driven intelligently, better fuel economy, says Fletcher. But the chassis is inevitably heavier, implying a loss of payload below that critical 25 tonnes, so he specified aluminium wheels and other weightsaving features on the trailer to restore the payload potential. It followed that the considerable cost of paring those kilograms could only be justified if Fletcher could be sure of converting them into revenue-earning payload. The on-board weighing equipment achieved that goal.

Both Fletcher and Griffiths carry agricultural produce for most of the year. Grain and commodities like rape seed are free flowing and are effectively self levelling in a tipper body — a quick touch on the brakes eliminates front or rear-biassed heaps, which means that front-rear weight balance is rarely a problem. Griffiths' low-cost Weylode device, which monitors front-end weight only, is therefore adequate in such cir cumstances, provided of course that the vehicle is level at the time.

No great accuracy was claimed for the original Weylode. A red line on the pressure gauge face indicates the nominal full-load condition; the reading is calibrated from time to time using Griffiths' own weighbridge at the spacious Hadlow grain-store site which doubles as the home base for his four eightwheelers.

Grain movements decline during the spring and summer, and both Fletcher and Griffiths keep their high-sided tippers occupied carrying sand and other aggregates; Fletcher's 38-tonners even bring crushed stone from the North. As those construction materials are less inclined to find their own level, there is more risk of the material being biassed forward or back, with consequent axle overloading.

The more sophisticated and expensive weighing systems like the Maywood, with load-cells giving separate as well as totalled front and rear readings, then come into their own — as they do if loading takes place on uneven ground. ' Roger Fletcher reckons that the Maywood system gives readings accurate to ±150kg, but he points out that an allowance has to be made for the practicalities of loading procedures. The tipper driver, watching the cab display, can give hand signals to the man at the controls of the digger-loader or the operators of the grain auger or elevator, telling them when his gross weight has been reached. But the flow cannot be stopped dead. Judgment based on experience is still needed to achieve a gross weight as close as possible to the plated maximum.

Several on-board weighing systems are available with a printer. A printed record of axle weights (necessarily computed for each vehicle using fixed unladen-weight data) is a useful bonus, even though the Department of Trade and Industry's Weights and Measures department is not empowered to authenticate on-board weigher readings.

So a print-out from an on-board weigher cannot be relied on as tangible supporting evidence for the defence in overloading case. By the same token, few companies receiving bulk commodities are prepared to take laden and empty on-board weigher readings as the basis for payment of weight delivered.

This is a source of regret to many tipper operators, including Fletcher and Griffiths, and of course to the suppliers of on-board weighing equipment.

The DTI refusal to give on-board weighers official or licensed status is undoubtedly based on the fact that they do not record the total vehicle weight. Changes in tare weight caused by fueltank contents and the carrying of auxilliary discharge equipment in chassismounted racks, for instance, are not registered by load-cells which, in practice, weigh only the body. Ell by Alan Bunting