PlentyHai

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

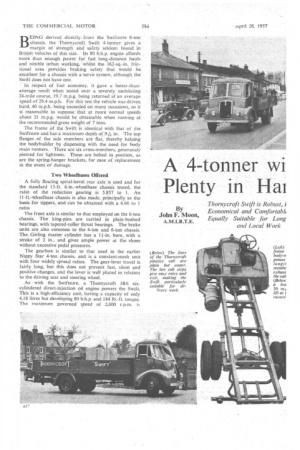

BEl-NG derived directly: from the Swiftsure 6-ton'

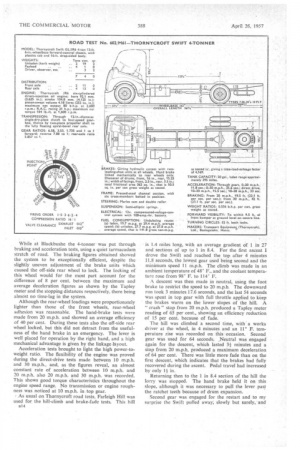

. chassis, the Thornycroft Swift 4-tonner. gives a margin of strength and safety seldom found in British vehicles of this size. Its 80 b.h.p. engine affords more than enough poWer, . for fast long-distance hauls and nimble urban Working, 'whilst the 362-sq.-in. frictional area provides braking safety that would be excellent for a chassi& with a 'servo system, although the Swift does not have one.

In respect of fuel economy, it gave abetter-thanaverage result when tested over a severely undulating 24-mile course, 19.7 m.p.g. being returned at an average speed of 294 mph, For this testthe vehicle was driven hard, 40 m.p.h. being exceeded on many occasions, so it is reasonable to suppose. that at more normal speeds about 21 m.p.g. would be obtainable when running at the recommended gross weight of 7 tons.

The frame of the Swift iS identical with that of the Swiftsure and has a maximum depth of 9Ain. The top flanges of the side members are flat, thereby helping the bodybuilder by dispensing with the need for body main runners. There are six cross-members, generously pierced for lightness. These are bolted in position, as are the spring-hanger brackets, for ease of replacement in the event of. damage.

Two Wheelbases Offered

A fully floating spiral-bevel rear axle is used and for the standard 13-ft. 6-in.-wheelbase chassis tested, the ratio of the reduction gearing is 5.857 to 1. An 11-ft.-wheelbase chassis is also made, principally, as the basis for tippers,.and can be obtained with a 6.66 to I ratio.

The front axle is similar to that employed on the 6-ton chassis. The king-pins are carried in plain-bushed bearings, with tapered-roller thrust bearings. The brake units are also common to the 4-ton and 6-ton chassis. The.Girling master cylinder has a 11-in. bore, with a stroke of 2 in., and gives ample power at the shoes without excessive pedal pressures.

The gearbox is similar to that usedin the earlier Nippy Star 4-ton chassis, and is a constant-mesh unit with four widely spread ratios. The gear-lever travel is fairly long, but this does not prevent fast, silent and positive changes, and the lever is well placed in relation to the driving seat and steering wheel.

As with the Swiftsure, a Thornycroft JR6 sixcylindered direct-injection oil engine powers the Swift. This is a high-efficiency unit, having a capacity of only 4.18 litres but developing 80 b.h.p. and 184 lb.-ft. torque. The maximum governed speed of 2,600 r.p.m. is

relatively high for an engine of this :size, but the unit is smooth-running at all speeds and pulls particularly Well at less. than 1,200 r.p.m. in the 4-tormer.

The unit tested ran more quietly than the engine fitted to the Swiftsure (The Commercial Minor, June 22, 1956) under all conditions, and even taking into account the lighter loadint, I can only assume that some subtle modification to the injection characteristics has been effected to reduce the combustion noise.

A plastids cab is built on to the standard all-stedl cab base, as used on .alt Thornycroft medium-range chassis, but weighs 1 cwt. less than the metal cab, bringing the total cab weight down to 31 cwt. A wide. four-piece wrap-round windscreen and narrow window and door. pillars give exceptional vision to the front and sides. The doors proper, in fact, are confined to the lower halves, the glazed portions consisting of little more than the glasses and supporting light-metal channels.

At first sight, the cab interior seems a little austere, principally because of the bare door-window frames, but this impression is soon dispelled. The interior finish of

the one-piece roof and back panel is smoother than usually found with glass-fibre moulding/ of this size and makes the use of lining panels unnecessary.

There is one rear window but smaller ones on each side of the centre glass would be advantageous, on the credit side is the fact that two rear-view mirrors are fitted. Strangely enough, only one windscreen wiper is supplied. The driving seat is a Chapman unit, adjustable vertically as well as horizontally, and, as usual, a telescopic steering column is fitted. This gives an overall degree of driving-position adaptability that is unique for a British vehicle of this capacity.

The test vehicle had covered 3,400 miles in service with the Thornycroft transport department and was thoroughly run-in. It had a standard Thornycroft 16-ft. drop-sided body and its kerb weight was 2 tons 194 cwt, The dry wei•ght of the chassis only is 2 tons 2 cwt. With a test load totalling 4 tons 1 cwt. and with driver and myself, gross weight was 7 tons 4 cwt.—slightly in excess of the recommended figure because of test gear.

For the first test the lorry was taken out to the eastern end of the Basingstoke by-pass and the graduated test tank topped up. A 12-mile run along the London road to Blackbushe Airport, was completed at an average speed of 30.5 m.p.h., despite some steep hilts and much heavy traffic which caused extensive use of the indirect gear rafios.. This run gave A fuel-consumption rate of

18 m.p.g. • The return trip to Basingstoke was made at an average speed of 28.2 m.p.h., and this time the fuel-consumption rate was 21.4 m.p.g. Although the average speed ' had beenreduced by only 2.3 m.p.h., the consumption rate was improved by 3.4.m.P.g. The lower rate is likely to prove more -rePresentative service. While, While at Blackbushe the 4-tonner was put through braking and acceleration tests, using a quiet tarmaeadam stretch of road. The braking figures obtained showed the system to be exceptionally efficient, despite the slightly uneven adjustment of the brake units which caused the off-side rear wheel to lock. The locking of this wheel would for the most part account for the difference of 8 per cent, between the maximum and average deceleration figures as shown by the Tapley meter and the stopping distances respectively, there being almost no time-lag in the system.

Although the rear-wheel loadings were proportionately lighter than those of the front wheels, rear-wheel adhesion was reasonable. The hand-brake tests were made from 20 m.p.h. and showed an average efficiency of 40 per cent. During these tests also the off-side rear wheel locked, but this did not detract from the usefulness of the hand brake in an emergency. The lever is well placed for operation by the right hand, and a high mechanical advantage is given by the linkage layout.

Acceleration tests brought to light the high power-toweight ratio. The flexibility of the engine was proved during the direct-drive tests made between 10 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h., and, as the figures reveal, an almost constant rate of acceleration between 10 m.p.h. and 20 m.p.h. also 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. was recorded. This shows good torque characteristics throughout the engine speed range. No transmission or engine roughness was noticed at 10 m.p.h. in top gear.

As usual on Thornycroft road tests, Farleigh Hill was used for the hill-climb and brake-fade tests. This hill B14 is 1.4 miles tong, with an average gradient of 1 in 27 and sections of up to 1 in 8.4. For the first ascent I drove the Swift and reached the top after 4 minutes 11.8 seconds, the lowest gear used being second and the minimum speed II m.p.h. The climb was made in an ambient temperature of 48° F., and the coolant temperature rose from 98° F. to 114° F.

A descent was then made in neutral, using the foot brake to restrict the speed to 20 m.p.h. The downward run took 3 minutes 17.6 seconds, and the last 54 seconds was spent in top gear with full throttle applied to keep the brakes warm on the lower slopes of the hill. A " crash " stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a Tapley meter reading of 65 per cent., showing an efficiency reduction of 15 per cent. because of fade.

The hill was climbed a second time, with a works driver at the wheel, in 4 minutes and an 11° F. temperature rise was recorded on this occasion. Second gear was used for 64 seconds. ,Neutral was engaged again for the descent, which lasted 31minutes and a stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a maximum deceleration of 64 per cent. There was little more fade than on the first descent, which indicates that the brakes had fully recovered during the ascent. Pedal travel had increased by only 14in.

Returning then to the 1 in 8.4 section of the hill the lorry was stopped. The hand brake held it on this slope, although it was necessary to pull the lever past the ratchet teeth because of drum expansion.

Second gear was engaged for the restart and to my surprise the Swift pulled away, slowly but surely,' and without any transmission judder. The engine torque was such as to be able to keep the vehicle moving at 'barely walking pace for nearly a minute until the gradient slackened sufficiently to allow the speed to build up towards maximum torque output The low radiator temperatures during these tests require explanation. The 1R6 engine is a cool-running unit even in the 6-ton chassis, but in the Swift it is rarely worked to its full capacity. Additionally, the standard 6-tonner radiator is retained, so the engine tends• to be Overcooled.

Cool-running Design This is not detrimental, however, because cool running is a feature of the engine design and fu41 Power is developed at very low engine temperatures. Bore-wear, problems are catered for by the use of chromium-plated top piston rings and no excessive wear of the bores•has been experienced \with vehicles in service over several years.

The normal running temperature of the engine during the greater part of the :tests was 95° F. in an ambient temperature of 50° F. The radiator is not pressurized and no thermostat is fitted, but, even so, it would be rare for the coolant temperature to rise to 160 F.

With the test weights removed the Swift was taken over the 24-mile fuel-test circuit to ascertain its average consumption rate when running unladen. There was little difference between the average speeds or the consumption.rates in each dii.ection, and the out runs resulted in an overall average rate of 27.7 m.p.g. at an average speed of 27.8 m.p.h.

When operating laden in one direction and returning empty it is safe to assume that an average consumption

rate of 23-24 m.p.g.would be recorded by operators. •

• A 44onner is handy for local deliveries—but time did

not permit me to conduct fuel-consumption tests to simulate these .conditions. A characteristic of-vehicles with a relatively high power-to-weight ratio, however, is that .conthluous stopping and starting does not increase the fuel consumption as much proportionally as with, vehicles with a lower power margin. The Swift should be quite economical on this type of work, therefore, and, by usual forward-control standards, the cab is very easy to enter. or leave.

Ease or Driving The Swift is an easy vehicle to drive, not only because Of 'the good visibilitY, but also because of the comfortable seating and the, light and welkplaCed controls.. The steering characteristics are particularly attractive, with light action, positive response and good lock.

Suspension also is of a high Standard, and whether the vehicle was laden or empty_ it held the road well. As a real test of suspension and steering I drove the Unladen vehicle over . an uneven and loose-surfaced stretch of road at 47 .m.p.h. (its maximum speed) with. my hands off the steering. wheel and there was no trace of wander. No dampers are fitted, but the progressive springs can deal ably with all surfaces.

Engine noise never becomes excessive: at normal speeds, in fact, it is possible to hear the fuel-filter relief Valve working, this filter being inside the cab. The cab' is free from rattles and creaks, but the draught-proofing

round the doors could be better. The price of the.

Vehicle has not been disclosed; , ,

All the normal routine maintenance jobs on the Swift will be done as on the Swiftstire;.which is particularly: easy to Work on, aided by a comprehensive tool kit.. Reference to the 'June 22. 1956, report of the Swittsure, therefore, Will give details of the maintenance; accessibility. .