'EU 8XT MEW

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

Page 96

Page 99

Page 100

Page 101

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

FOR two years or more, manufacturers in this country have been designing and testing vehicles at well above the existing Construction and Use weight limits, and there has been considerable economic argument in favour of the early adoption of higher weights. Earls Court this year shows just what a tremendous design and engineering effort has been put into meeting this expected change; the Show is liberally sprinkled with heavier-than-legal models which cannot yet be operated at their designed weights.

Even at the last Show in 1968 a major talking point was the prospect of 38or 40-ton-gross combination weights for artics. In the interim period this figure has gone up to 44 tons—which is what the rest of Europe is thinking about—and the Ministry of Transport has accepted the idea of a

56-ton tractor/drawbar trailer limit as at least a basis for discussion. And it is not only the permitting of the highest weights which would give new impetus to road transport productivity: 24-ton six-wheelers and 30-ton eight-wheelers are among the prospects in the lower ranges if new regulations are made. Yet still we wait for a decision.

Major interest in the chassis field this year centres on the higher-weight trucks and the new, more powerful engines, while for passenger operators the Leyland National is the outstanding vehicle. Integral construction, with massive body members designed to protect the occupants in the event of roll-over, is new in this field in this country. Clearly the result of considerableand continuing-research and design work by Leyland engineers, the bus is due to go into production before the next show.

On the truck side, lack of decision on future legislation is creating many problems for engineers trying to design nextgeneration vehicles. Many questions are still open, not only as to what the future maximum weights will be, but also what axle spreads will be linked to them, what configuration will be considered acceptable in a tractive unit for particular weights and so on. Talking to design engineers one discovers, not surprisingly, that they have investigated the advantages and disadvantages of various layouts for various gross weights; the 'fact that so many different answers have resulted is partly a result of the legislative indecision, partly a matter of suiting a company's own particular plans and practices and, no doubt. to some extent a reflection of the individual preference or hunch of the chief engineer in control.

One of the big decisions (which may be influenced by Code of Practice guidance) is whether to go for single or double drive on tractive units for particular weights. There seems to be a considerable belief that, if one could get 11.5 or 12 tons load on a driving axle, then single drive would be sufficient for many of the new generation of heavies, at least those likely to spend their lives on motorways. At the moment, any increase on the 10-ton axle limit seems no more than a faint possibility, but if one came it could alter several decisions on layout.

There are 4 x 2 and 6 x 2 twin-steer tractive units for 38 tons shown by Atkinson, Fodens and Seddon. but will a 10-ton axle load meet a legal or, more likely, Code of Practice requirement for this weight or will the new 6 x 4 model offered by ERF for 38 tons be needed? Will the single-driving axle be limited to a gross weight of 36 tons as suggested in the display by ERF of its Gardner 8LXB-engined four-wheeler for this weight, or will it be 34 tons, the weight quoted by Atkinson and Guy for their new two-axle tractive units?

In talking of tractive units for the new gross weights one must not forget the Leyland 6 x 4 with gas turbine engine, whose development now goes one stage further; three examples on bodybuilders' stands at Earls Court are said to be ready for use by operators, though for the time being not at the designed weight of 44 tons. The biggest new tractive unit at the Show is Scammell's eight-wheeled Samson, with a second steering axle ahead of the double-drive bogie.

Atkinson's twin-steer tractive unit with Gardner 8LXB engine provides an example of the sort of difficulty which faces a maker through the lack of legal decisions, since this has had to be designed in two wheelbase versions. For semi-trailers to standards anticipated for 38 tons, the wheelbase is 1 Ift 6in. but if 44 tons comes then semi-trailers possible for this weight would have a front overhang that would require the use of the 12ft 6in.-wheelbase model.

This illustrates the way in which manufacturers have had to speculate in developing new heavier-than-normal models. Guy admits that its eight-wheeler for use in a tractor-drawbar trailer combination at 56 tons is based on a good deal of speculation. Comparing this vehicle with the usual European tractive unit, it appears that the rear overhang is too short. but Guy has fixed a wheelbase which it thinks will be specified for a 30-ton eight-wheeler and, keeping within the current length limit of 11 metres for rigids (unlikely to be changed), has decided on the overhang dimension. The vehicle itself has the biggest British engine at the Show—a Cummins turbocharged 350 bhp unit giving 6.3 bhp per ton—and is very interesting. It is based generally on the 26-ton-gross three-axle vehicle shown by Guy two years ago, but now a four-spring rear suspension is used. The vehicle is designed to carry a fully loaded 20ft container as well as towing a trailer carrying a second one.

The Guy eight-wheeler can operate at 30 tons gross without exceeding current axle weight limits and in fact gets away with 9.00-20 tyres at the rear bogie, with 10.00--20 at the front_ But of all the suggestions put to the MoT by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders the 30-ton eight-wheeler is. in my view, the least likely to be accepted. This is because the eight-wheeler plays no part in the general European picture of vehicle operation and it is logical that future UK legislation will follow the general standards set on the Continent. When 56 tons is put forward as a means of moving two loaded 2011 containers it may have to be with a "double-bottom" combination where an artic draws an independent trailer normally made up of a semi-trailer on a dolly. The 56-ton combination could be a 32-ton artic and 26-ton "trailer".

An eight-wheeler designed for 30 tons gross is also shown by Fodens, but this is not intended to be used with a drawbar trailer and therefore the chassis has a 180 bhp Gardner 6LXB diesel. Previously the biggest eight-wheeler offered by Fodens had a gross limit of 26 tons and this is actually

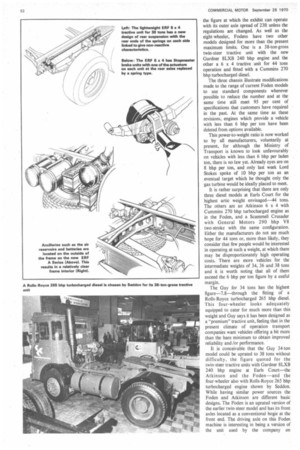

the figure at which the exhibit can operate with its outer axle spread of 2311 unless the regulations are changed. As well as the eight-wheeler, Fodens have two other models designed for more than the present maximum limits. One is a 38-ton-gross twin-steer tractive unit with the new Gardner 8LXI3 240 bhp engine and the other a 6 x 4 tractive unit for 44 tons operation and fitted with a Cummins 270 bhp turbocharged diesel.

The three chassis illustrate modifications made to the range of current Foden models to use standard components wherever possible to reduce the number and at the same time still meet 95 per cent of specifications that customers have required in the past. At the same time as these revisions, engines which provide a vehicle with less than 6 bhp per ton have been deleted from options available.

This power-to-weight ratio is now worked to by all manufacturers, voluntarily at present, for although the Ministry of Transport is known to look unfavourably on vehicles with less than 6 bhp per laden ton, there is no law yet. Already eyes are on 8 bhp per ton, and only last week Lord Stokes spoke of 10 bhp per ton as an eventual target which he thought only the gas turbine would be ideally placed to meet.

It is rather surprising that there are only three diesel models at Earls Court for the highest artic weight envisaged-44 tons. The others are an Atkinson 6 x 4 with Cummins 270 bhp turbocharged engine as in the Foden, and a Scammell Crusader with General Motors 290 bhp V8 two-stroke with the same configuration. Either the manufacturers do not see much hope for 44 tons or, more than likely, they consider that few people would be interested in operating at such a weight, at which there may be disproportionately high operating costs. There are more vehicles for the intermediate weights of 34, 36 and 38 tons and it is worth noting that all of them exceed the 6 bhp per ton figure by a useful margin.

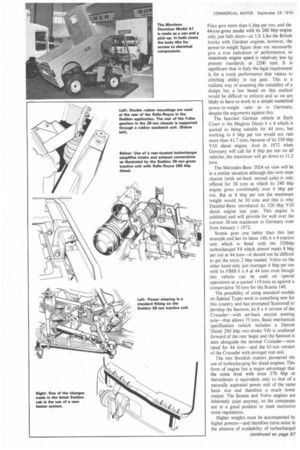

The Guy for 34 tons has the highest figure-7.8—through the fitting of a Rolls-Royce turbocharged 265 bhp diesel. This four-wheeler looks adequately equipped to cater for much more than this weight and Guy says it has been designed as a "premium" tractive unit, feeling that in the present climate of operation transport companies want vehicles offering a bit more than the bare minimum to obtain improved reliability and/or performance.

It is conceivable that the Guy 34-ton model could be uprated to 38 tons without difficulty, the figure quoted for the twin-steer tractive units with Gardner 8LXB 240 bhp engine at Earls Court—the Atkinson and the Foden--and the four-wheeler also with Rolls-Royce 265 bhp turbocharged engine shown by Seddon. While having similar power sources the Foden and Atkinson are different basic designs. The Foden is an uprated version of the earlier twin-steer model and has its front axles located as a conventional bogie at the front end. The driving axle on this Foden machine is interesting in being a version of the unit used by the company on high-weight tractors but modified to allow faster road speeds by detail changes in the hub-reduction components and with a differential lock system devised by Fodens. The Atkinson on the other hand has a set-back second steering axle and this has air suspension. Although it uses the same Gardner 8LXB engine as the Atkinson, the driving axle is the new Kirkstall D85 with differential lock and hub reduction.

The two-axle Seddon 38-ton-gross model comes in the 32:four series, following the basic specification of the 32-ton model. The 32-ton tractive unit was designed originally to cater for 38 tons operation, so the new vehicle has been produced simply by fitting the higher output Rolls-Royce engine and, like all the heavies already referred to except the Fodens, drives through a Fuller gearbox. But as the front axle load is higher for the new application, power steering is made standard on the model instead of an option.

ERF's 38-ton-gross tractive unit offering is a 6 x 4 chassis fitted with Cummins 230 bhp engine and Fuller gearbox and is designed generally as a light-weight chassis. The aim—to get to an unladen weight comparable with that of an equivalent two-axle model—has been achieved, at least within 5cwt or so. The vehicle has a new four-spring suspension with inter-linked ends for the springs on each side to give non-reactive characteristics. The rear bogie uses Eaton axles with Stopmaster brakes which, like the low-profile 15-19.5 tyres, are used in the interests of reducing weight. Probably considering that 36 tons is the maximum feasible with single-axle drive, ERF puts this limit on its model fitted with Gardner 8LXB engine. Like the 38-ton unit, this is an example of the A Series which is being developed by ERF and it is expected that the full ERF goods range will be to the same pattern within the next two years—another example of a trend towards rationalization_ Another model which is for weights in excess of the current C and U maximum figures is the AEC Mammoth Major V8 6 x 4 with V8 270 bhp diesel. This is not a new model having been seen at the Scottish Show last year, but whereas the maximum weight quoted then was 44 tons, the chassis is now said to be capable of operation at up to 56 tons. This can only refer to its rating for use on Special Types work, for the power-to-weight ratio of 4.8 bhp per ton at 56 tons would not be considered acceptable for normal haulage. At 44 tons, however, where the power-to-weight ratio is almost 6.2 bhp per ton, performance should be acceptable although with this high-revving engine there would not be the degree of performance found with most of the other high-output diesels in the top-weight chassis—these produce their maximum bhp at much lower engine rpm.

At this point it is relevant to consider the non-UK exhibitors at Earls Court. Each of the five Continental heavy-vehicle manufacturers at the Show has a model that is designed for a gross weight in excess of the current British maximum. DAF of Holland (who is launching a concentrated UK sales drive) has two of its new range with luxury tilt cabs. One of them is an FT220 with 201 bhp turbocharged diesel that is rated for 36 tons. There is also one of the older FTT2600 6 x 4 tractive units for 46 tons and with a 230 bhp engine. The power-to-weight ratios of these at 5.6 and 4.4 bhp per ton respectively illustrate that high power is not considered essential in Holland with its shortage of hills. But at 6 bhp per ton gross limits the maximum weights would be 33.5 tons and 38.3 tons and these figures will apply in Germany where 6 bhp per ton is legally required now. In 1971 8 bhp per ton is needed there in the case of up to 32 ton vehicles and at the present power rating the FT2200 will be restricted to 25 tons in this case.

Fiat also has its new ones with highclass cabs and designed for weights between 32 and 44 tons. The cabs are fixed but there appears to be no reason why they could not be made as tilt units, and in fact Fiat's French company—Unic—now uses the same basic cab in tilting form. When it comes to power-to-weight ratio, three of the Fiats give more than 6 bhp per ton, and the 44-ton-gross model with its 260 bhp engine only just falls short—at 5.9. Like the British trucks with Gardner engines, however, the power-to-weight figure does not necessarily give a true indication of performance, as maximum engine speed is relatively low by present standards at 2200 rpm. It is significant that in Italy the legal requirement is For a truck performance that relates to climbing ability in top gear. This is a realistic way of assessing the suitability of a design but a law based on this method would be difficult to enforce and so we are likely to have to work to a simple numerical power-to-weight ratio as in Germany, despite the arguments against this.

The heaviest German vehicle at Earls Court is the Magirus Deutz 6 x 4 which is quoted as being suitable for 44 tons, but working to 6 bhp per ton would not rate more than 41.7 tons, because of its 250 bhp V 10 diesel engine. And in 1972 when Germany will call for 8 bhp per ton on all vehicles, the maximum will go down to 31.2 tons.

The Mercedes-Benz 2024 on view will be in a similar situation although this twin-steer chassis (with set-back second axle) is only offered for 38 tons at which its 240 bhp engine gives comfortably over 6 bhp per ton. But at 8 bhp per ton the maximum weight would be 30 tons and this is why Daimler-Benz introduced its 320 bhp VIO diesel engine last year. This engine is exhibited and will provide for well over the current 38-ton maximum in Germany even from January 11972.

Scania goes one better than this last example and has its latest 140, 6 x 4 tractive unit which is fitted with the 350bhp turbocharged V8 which almost meets 8 bhp per ion at 44 tons—it should not be difficult to get the extra 2 bhp needed. Volvo on the other hand only just manages 6 bhp per ton with its FB88 6 x 4 at 44 tons even though this vehicle can be used on special operations at a quoted 110 tons as against a conservative 70 tons for the Scania 140.

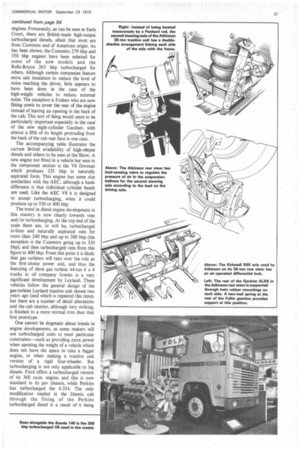

The possibility of using standard models on Special Types work is something new for this country and has prompted Scammell to develop the Samson, an 8 x 4 version of the Crusader—with set-back second steering axle—that allows 75 tons. Basic mechanical specification (which includes a Detroit Diesel 290 bhp two-stroke V8) is unaltered forward of the rear bogie and the Samson is seen alongside the normal Crusader—now rated for 44 tons—and the 65-ton version of the Crusader with stronger rear end.

The two Swedish makers pioneered the use of turbocharging for diesel engines. This form of engine has a major advantage that the noise level with even 270 bhp or thereabouts is equivalent only to that of a naturally aspirated power unit of the same basic size and therefore a much lower output. The Scania and Volvo engines are inherently quiet anyway, so the companies are in a good position to meet restrictive noise regulations.

Higher weights must be accompanied by higher powers—and therefore extra noise in the absence of availability of turbocharged continued on page 97 engines. Fortunately, as can be seen at Earls Court, there are British-made high-output turbocharged diesels, albeit that most are from Cummins and of American origin. As has been shown, the Cummins 270 bhp and 350 bhp engines have been selected for some of the new models and the Rolls-Royce 265 bhp turbocharged for others. Although certain companies feature extra cab insulation to reduce the level of noise reaching the driver, little appears to have been done in the case of the high-weight vehicles to reduce external noise. The exception is Fodens who are now fitting cowls to cover the rear of the engine instead of leaving an opening in the back of the cab. This sort of thing would seem to be particularly important especially in the case' of the new eight-cylinder Gardner, with almost a fifth of its length protruding from the back of the cab rear face in one case.

The accompanying table illustrates the current British availability of high-ottput diesels and others to be seen at the Show. A new engine not fitted in a vehicle but seen in the component section is the V8 Dorman which produces 235 bhp in naturally aspirated form. This engine has some size similarities with the AEC, although a basic difference is that individual cylinder heads are used. Like the AEC V8 it is designed to accept turbocharging, when it could produce up to 350 or 400 bhp.

The trend in diesel engine development in this country is now clearly towards vees and/or turbocharging. At the top end of the scale there are, or will be, turbocharged in-lines and naturally aspirated vees for more than 240 bhp and up to 300 bhp (the exception is the Cummins going up to 350 bhp), and then turbocharged vees from this figure to 400 bhp. From this point it is likely that gas turbines will take over the role as the first-choice power unit, and thus the featuring of three gas turbine 44-ton 6 x 4 trucks in oil company liveries is a very significant development by Leyland. These vehicles follow the general design of the gas-turbine Leyland tractive unit shown two years ago (and which is repeated this time), but there are a number of detail alterations and the cab interior, although very striking, is finished to a more normal trim than that first prototype.

One cannot be dogmatic about trends in engine developments, as some makers will use turbocharged units to meet particular constraints—such as providing extra power when uprating the weight of a vehicle which does not have the space to take a bigger engine, or when making a tractive unit version of a rigid four-wheeler. But turbocharging is not only applicable to big diesels. Ford offers a turbocharged version of its 360 cu.in. engine, and this is now standard in its psv chassis, 'while Perkins has turbocharged the 6.354. The only modification needed in the Dennis cab through the fitting of the Perkins turbocharged diesel is a result of it being more convenient to put the air intake cleaners outside the cab. So the interior cowl over the engine is smaller. Except for the engine and the higher-capacity version of the Dennis U-type gearbox, the Defiant 24-ton-gross tractive unit is the same as the 15.5-ton four-wheeler. Like the latter model, a major feature of the 24-ton model is that it is based on a concept of providing the biggest possible payload capacity, and the tractive unit should allow a 17-ton payload within a 24-ton gross weight limit.

Turbocharged versions of new Albion Reiver and Clydesdale models are seen at the Show. The naturally aspirated engines used in these chassis give 138 bhp, which is increased to 155 bhp with turbocharging. The two engines are basically the same. In the case of the Perkins turbocharged 6.354, power goes up from 120 bhp to 155 bhp. A factor in this larger power increase is Perkins' decision to improve thermal characteristics by the use of an intercooler which reduces the temperature of the combustion air. This is a very significant automotive application of a principle proved elsewhere.

The new Perkins turbocharged 6.354 is quite different from the naturally aspirated unit and Perkins does not consider it sensible to build turbocharged and non-turbocharged engines to identical basic specifications. Although it must be admitted that modifications, for example to increase strength, needed for the turbocharged model, add to the cost of the non-turbocharged diesel, other makers obviously differ—in particular Scania. and Volvo— and it is now common for new engines to be designed to take charging. As stated, this applies to the AEC and Dorman V8s and it also applies to the Leyland 500 engine with fixed head, which can give up to 260 bhp when turbocharged.

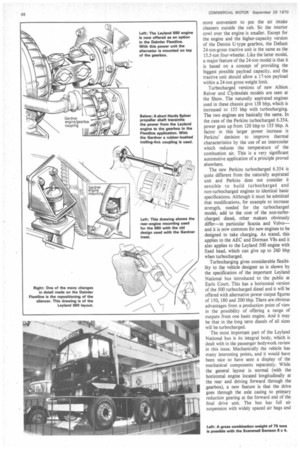

Turbocharging gives considerable flexibility to the vehicle designer as is shown by the specification of the important Leyland National bus introduced to the public at Earls Court. This has a horizontal version of the 500 turbocharged diesel and it will be offered with alternative power output figures of 150, 180 and 200 bhp. There are obvious advantages from a production point of view in the possibility of offering a range of outputs from one basic engine. And it may be that in the long term diesels of all sizes will be turbocharged.

The most important part of the Leyland National bus is its integral body, which is dealt with in the passenger bodywork review in this issue. Mechanically the vehicle has many interesting points, and it would have been nice to have seen a display of the mechanical components separately. While the general layout is normal (with the horizontal engine located longitudinally at the rear and driving forward through the gearbox), a new feature is that the drive goes through the axle casing to primary reduction gearing at the forward end of the, final drive unit. The bus has full air suspension with widely spaced air bags and

the steering is novel in that the hydraulically assisted rack and pinion unit is mounted on the front axle itself.

The Leyland National is not the only new psv at Earls Court with features of particular interest. There is, for example, the new Bedford YRQ which has a central vertical engine mounted sufficiently low to permit a normal-height floor. Then there are the Bristol and Daimler chassis which are now fitted with Leyland engines as options—the 500 and 680 respectively. And on the Seddon stand is the RU which is now making an impact on the psv field, together with the Perkins V8-engined Pennine IV which is seen for the first time at Earls Court.

With the use of higher-power diesels with very high torque outputs, the Fuller twin-countershaft Roadranger gearbox comes into its own. Fodens are the only British company with a gearbox designed capable of meeting the torque requirements for 44 tons and 240 bhp plus; every other high-weight truck has a Fuller Roadranger, and the version in the Guy 56-ton, g.c.w. eight-wheeler has a torque capacity of 1200 lb ft. In the clutch field the common use of Lipe-Rollway twin-plate equipment is interesting but this again is not a solely American field, there being a Borg and Beck twin-plate clutch in one of the Guy chassis.

No completely new cabs are intoduced at Earls Court this year. The latest Fiat and DAF designs are to be seen, of course, to illustrate with the Scania and MercedesBenz the best in Europe. But British cabs are nowhere near so far behind as they used to be. Improvements have been made gradually over the years and now the general standard is fairly high, as is shown by the revised Seddon, ERF and Foden designs, each of which has been improved in detail for the Show. The greatest changes have been made by Seddon and ERF. In both cases there is improved insulation, interior trim and heating.

In the brakes field, there is little to report. Some manufacturers go for spring brakes for secondary and parking while others use lock actuators. But the new Leyland Terrier is novel in having a "power hydraulic" system produced by Clayton Dewandre. This is another pioneering application by the designers who produced the original BMC FJ with its tandem master

cylinder /dual actuator brakes. The essential parts are hydraulic accumulators for each of the independent front and rear axle circuits. The accumulators have nitrogenfilled bags which are compressed by fluid

from a dual hydraulic pump and store at high pressure of around 2,000 psi for use on brake application.

Many changes seen at the Show are not startling but nevertheless important to operators. In this category are the alterations made to the Mandator and Mercury by AEC. These include a new twin thermostat and revised cooling system, new rear engine mountings and different silencer location. The changes made by Fodens to their model programme are also important in that they allow easier production. The bigger engines in the new A-Series from ERF have been referred to. But there is

equal interest in other new, aspects of the design. including a much "cleaner" layout of units which gives an uncluttered frame interior.

It would be wrong to maintain that this Show is only interesting from the aspect of high-weight haulage models, high-power engines and turbocharging; under the surface there are many changes that are possibly of more importance to the user. There are, for example, interesting trend§ among the smaller vehicles. In the lightest category, the Morrison-Electricar Al van shows awareness of a wider potential market for light electrics, while among the heavier local delivery vehicles there is a marked increase in models equipped with 16in. wheels and more than the usual number of axles in order to achieve a loading height of about 3ft.