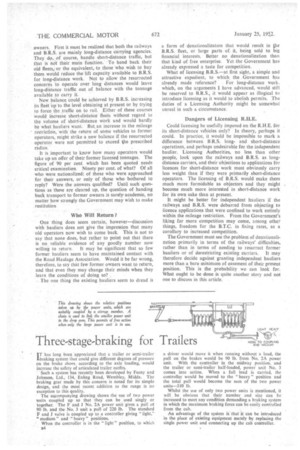

Will 40 Miles be the Limit?

Page 37

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Asks Serviteur

WFIAT do you think the Government will do? Do you think it will denationalize road haulage?" These are the recurrent questions : .

of the moment. • .

.. With Parliament in recess; with no hint of the Government's detailed intentions; with some hauliers bitter and critical of the Government; with others, more cynical and realistic, doubtful of anything much .being done for them; with the Minister of Transport polite to the Road Haulage Association, but enigmatic towards its proposals; with Mr. Churchill having made clear that any Conservative promise on this or any other matter before the Election, was not made by him—the hush can be heard for miles!

Hopes Too High Many hauliers have too high expectations of the new Government, and they, are bound to be disappointed and perhaps embittered when its proposals are made known. It might, for this reason, be as well to examine the position as dispassionately as possible and with as much logic and realism as I can muster. Operators may then expect the worst, hope for the best and, if they are lucky, get something in between.

There is no hope of this or any Government deciding to reverse all previous thinking by giving roads and road transport priority over the railways. We must accept that, in the Government's view, the railways are the main problem. On the other hand, British Road Services may yet become a fairly consistently profit. making concern and help to pay for British Railways' losses; anything that would weaken or destroy the chances of B.R.S. achieving financial success will therefore be avoided.

While in Opposition, the Conservative Party saw little of the good points of B.R.S.; in power, it may see little of the bad ones, unless it goes looking for them. Some. hauliers believe that the Transport (Amendment) Bill of 1951 represented the least that the Conservatives would do for them. This is by no means certain. In any event, the responsibilities of government will by now have impressed en the Conservatives that the hauliers' position is by no means the only problem.

What Did They Promise ?

There seems to be nothing which justifies the view, held by many hauliers on the strength of pre-election speeches of Conservative M.P.s and candidates, that the Conservative Party promised the abolition of the mileage restriction on A and B licensees and must accordingly consider the extent of the modification that has since been reliably promised.

The Transport (Amendment) Bill included a provision to raise the restriction from the present 25 miles' to 60 miles' radius. Such a change represents a radial increase of 140 per cent. The extension from the smaller to the larger radius would represent an increase in area of operation of about 475 per cent. The latter figure gives a much more realistic indication of the practical effect of the extension than does the percentage increase in the radius. An increase of 475 per cent. in operating area may not be agreeable to the new Government.

It may find itself unable to grant more than a 40-mile radius to Aand B-licence holders, a belief for which 1 have several reasons. The Transport Act, .1947, used 40 road miles—the distance beyond which the goods. travelled—as part of the definition of long-distance carriage of goods for compulsory acquisitions. During the war, uncontrolled carriers were permitted a carrying _distance of 60 miles. A radius of 40 miles would in practice give a similar average carrying distance.

Forty miles' radius covers the critical hauls beyond which return loads assume importance and below which return loads tend to be less economic than a quick and empty run home for the next outward load. The first draft of the Transport Bill proposed a radial restriction of 40 miles for C-licensees—an obvious indication that that was considered the outside limit of short-distance work.

Whilst 40 miles' radius would increase competition with the British Transport. Commission, it is not so. much greater than 25 miles that the Road Haulage and

Railway Executives could not recover from it. This increase might not, in any event, be great, because many hauliers lack capacity for more work. If Lord Leathers is to achieve co-ordination of transport, which the B.T.C. has so far failed to do, anything more than 40 miles would increase the difficulties. (It should be borne in mind that Lord Leathers had no need to make election promises. On the contrary, during the war, he said that something more than the road-rail "Square Deal" agreement would be necessary to put the country's transport on a satisfactory basis.)

Wooing Labour

An increase to 40 miles could be claimed as fulfilling the promise of modification." Mr. Churchill is too anxious to avoid clashes with the Labour Party and the trade unions to wish to create a state of affairs which Labour would pledge itself to reverse if it came to power again. Labour might be prepared to tolerate a 40-mile radius.

It seems inevitable that with a limit on mileage (let us ignore the question of how many miles) there must.be a permits system, if only because the absence of permits, plus a restriction, would make that restriction more rigid even than at present. There remains the question

of the permit-issuing authority. Although one could wish it so, it is difficult to see how the R.H.E. could be left without any say in the issue of permits.

It would seem logical that an organization should be given overriding power in the granting of permits if it is to be responsible for long-distance haulage and is to be an integral part of a co-ordinated transport system. Otherwise, a mileage restriction would, in practice, become a cipher only. The radius restriction is a method of rationing or apportioning traffic between two carrying agencies—the independents and the nationalized. The permits system is intended to give flexibility.

I must now consider the question whether it is practicable to hand back 13.R.S..or Darts of it to former owners. First it must be realized that both the railways and B.R.S. are mainly long-distance carrying agencies. They do, of course, handle short-distance traffic, but that is not their main function. To hand back their old fleets; or the equivalent, to those who wish to buy them would reduce the lift capacity available to B.R.S. for long-distance work. Not to allow the resurrected concerns to operate over long distances would leave long-distance traffic out of balance with the tonnage available to carry it.

New balance, could be achieved by B.R.S. increasing its fleet up to the level obtaining at present or by trying to force the traffic on to rail. Either of these courses would increase short-distance fleets without regard to the volume of short-distance work and would hardly be what hauliers want. But, an increase in the mileage restriction, with the return of some vehicles to former operators, might strike a new balance if the resurrected operator were not permitted to exceed the prescribed radius.

It is important to know how many operators would take up an offer of their former licensed tonnages. The figure of 90 per cent. which has been quoted needs critical examination. Ninety per cent. of what? Of all who were nationalized; of those who were approached for their answers, or only of those who bothered to reply? Were the answers qualified? Until such questions as 'these are cleared up, the question of handing back transport to-former owners is surely, academic, no matter how strongly the Government may wish to make restitution • • Who Will Return ?

One thing does seem certain, however—discussion with hauliers does not give the impression that many old operators now wish to come back. This is not to say that none does, but rather to point out that there is no reliable evidence of any goodly number now

willing to return. It may be significant that so few former hauliers seem to have maintained contact with the Road Haulage Association. Would it be far wrong, therefore, to say that few former owners want to return, and that even they may change their minds when they learn the conditions of doing so?

The one thing the existing hauliers seem to dread is a form of denationalization that would result in Lhe B.R.S. fleet, or large parts of it, being sold to big financial interests. Better no denationalization than that kind of free enterprise. Yet the Government has already expressed a taste for competition.

What of licensing B.R.S.—at first sight, a simple and attractive expedient, to which the Government has already made reference? For long-distance work, which, on the arguments I have advanced, would still be reserved to B.R.S., it would appear as illogical to introduce licensing as it would to abolish permits. The duties of a Licensing Authority might be somewhat unreal in such a circumstance.

Dangers of Licensing R.H.E.

Could licensing be usefully imposed on the R.H.E. for its short-distance vehicles only? In theory, perhaps it could. In practice, it would be impossible to mark a difference between B.R.S. longand short-distance operations, and perhaps undesirable for the independent haulier. Licensing Authorities, no less than other people, look upon the railways and B.R.S. as longdistance carriers, and their objections to applications for licences for short-distance work must obviously carry less weight than if they were primarily short-distance operators. The licensing of B.R.S. would make them much more formidable as objectors and they might become much more interested in short-distance work for its own sake than at present.

It might be better for independent hauliers if the railways and B.R.S. were debarred from objecting to licence applications that were confined to work entirely within the mileage restriction. From the Government's liking for more competition may come, among other things, freedom for the B.T.C. in fixing rates, as a corollary to increased competition.

The Government must see the problem of denationalization primarily in terms of the railways' difficulties, rather than in terms of needing to resurrect former

hauliers or of derestricting existing carriers, It may therefore decide against granting independent hauliers more than a bare minimum of easement of their present position. This is the probability we can look for. What ought to be done is quite another story and not one to discuss in this article.