Paul Mungo spends a day with longdista driver Norman Plump ton. Photos by Steve

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE RHM yard at six in the morning is illuminated by two yellow floodlights. It's still dark and cold, though the wind is trapped by the wall of buildings that make up the foods plant.

Norman Plumpton has been here for half an hour, checking his tractive unit and trailer, checking the oil level, the lights, and the tyres.

"We'll get a log book and we'll be away," he says to the supervisor. He's anxious to leave as soon as possible, to miss the rUsh-hour traffic through Londn and the interminable snarl-up at the Blackwell Tunnel.

The run is from the Ashford depot to Nottingham: if he misses the traffic he can do it in six hours; if not, it could take seven or eight.

The load this morning is 22 oallet-loads of Energen crispbread, made in Ashford, and destined for distribution throughout the Midlands.

"Most days I start at five, miss most of the holdups. and get almost a clear run through London. If you start at six the traffic has time to build up. All you need is one little snag, one little hold-up, and a bottleneck builds up."

Still, even at this hour the roads to London are fairly clear. The lights of the huge ERF 35R2 tractive unit are on, gloomily piercing the half-light of dawn. It is pulling a 40ft trailer.

The rig, including modifications to the trailer carried out by Tautliner, cost, Norman guesses, about £22,000.

"The company doesn't mess about with the equipment and they don't care about the expense. This vehicle has to be in tip-top condition, so if I say I want something for the truck,

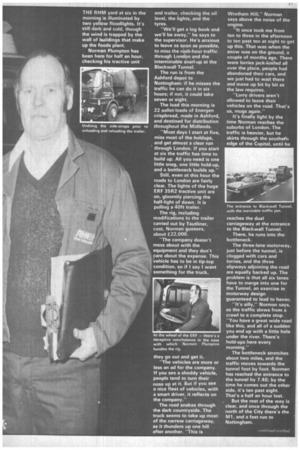

Al the wheel of the ERF — there's a deceptive nonchalance in the ease with which Norman Plumpton handles the rig.

they go out and get it.

"The vehicles are more or less an ad for the company. If you see a shoddy vehicle, people tend to turn their nose up at it. But if you see a nice fleet of vehicles, with a smart driver, it reflects on the company."

The road snakes through the dark countryside. The truck seems to take up most of the narrow carriageway, as it thunders up one hill after another. "This is Wrotham Hill," Norman says above the noise of the engine.

"It once took me from ten to three in the afternoon to ten past ten at night to get up this. That was when the snow was on the ground, a couple of months ago. There were lorries jack-knifed all over the place, people had abandoned their cars, and we just had to wait there and move up bit by bit as the law requires.

"Lorry drivers aren't allowed to leave their vehicles on the road. That's us, mugs again."

It's finally tight by the time Norman reaches the suburbs of London. The traffic is heavier, but he skirts through the southefn edge of the Capital, until he

The entrance to Blackwell Tunnel, with the inevitable traffic lam

reaches the dual carriageway at the entrance to the Blackwell Tunnel. There, he runs into the bottleneck.

The three-lane motorway, just before the tunnel, is clogged with cars and lorries, and the three slipways adjoining the road are equally backed up. The problem is that all six lanes have to merge into one for the Tunnel, an exercise in motorway design guaranteed to lead to havoc.

"It's silly," Norman says, as the traffic slows from a crawl to a complete stop. "You have a great wide road like this, and all of a sudden you end up with a little hole under the river. There's hold-ups here every morning."

The bottleneck stretches about two miles, and the traffic moves towards the tunnel foot by foot. Norman has reached the entrance to the tunnel by 7.40; by the time he comes out the other side, it's ten past eight. That's a half an hour lost.

But the rest of the way is clear, and once through the north of the City there's the and a fast run to Nottingham.