T he deepening rail crisis could not have come at a

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

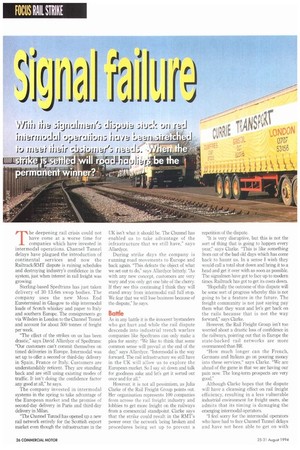

worse time for companies which have invested in intermodal operations. Channel Tunnel delays have plagued the introduction of continental services and now the Railtrack/RMT dispute is ruining schedules and destroying industry's confidence in the system, just when interest in rail freight was growing.

Sterling-based Spedtrans has just taken delivery of 30 13.6m swop bodies. The company uses the new Moss End Euroterminal in Glasgow to ship intermodal loads of Scotch whiskey and paper to Italy and southern Europe. The consignments go via Wilsden in London to the Channel Tunnel and account for about 500 tonnes of freight per week.

"The effect of the strikes on us has been drastic," says David Allardyce of Spedtrans: "Our customers can't commit themselves on timed deliveries in Europe. Intermodal was set up to offer a second or third-day delivery in Spain, France or Italy. Customers are understandably reticent. They are standing back and are still using existing modes of traffic. It isn't doing the confidence factor any good at all," he says.

The company invested in intermodal systems in the spring to take advantage of the European market and the promise of second-day delivery in Paris and third-day delivery in Milan.

"The Channel Tunnel has opened up a new rail network entirely for the Scottish export market even though the infrastructure in the UK isn't what it should be. The Chunnel has enabled us to take advantage of the infrastructure that we still have," says Allardyce.

During strike days the company is running road movements to Europe and back again. This defeats the object of what we set out to do," says Allardyce bitterly "As with any new concept, customers are very wary and you only get one bite of the cherry. If they see this continuing I think they will stand away from intermodal rail full stop. We fear that we will lose business because of the dispute," he says.

Battle

As in any battle it is the innocent bystanders who get hurt and while the rail dispute descends into industrial trench warfare companies like Spedtrans can only make a plea for sanity: -We like to think that some common sense will prevail at the end of the day," says Allardyce. "Intermodal is the way forward. The rail infrastructure we still have in the UK will allow us to explore the European market. So I say sit down and talk for goodness sake and let's get it sorted out once and for all."

However, it is not all pessimism, as Julia Clarke of the Rail Freight Group points out. Her organisation represents 100 companies from across the rail freight industry and lobbies to get more freight on the railways from a commercial standpoint. Clarke says that the strike could result in the RMT's power over the network being broken and procedures being set up to prevent a repetition of the dispute.

"It is very disruptive, but this is not the sort of thing that is going to happen every year," says Clarke. "This is like something from out of the bad old days which has come back to haunt us. In a sense I wish they would call a total shut down and bring it to a head and get it over with as soon as possible. The signalmen have got to face up to modern times. Railtrack has got to get its costs down.

"Hopefully the outcome of this dispute will be some sort of progress whereby this is not going to be a feature in the future. The freight community is not just saying pay them what they want and let's get back on the rails because that is not the way forward," says Clarke.

However, the Rail Freight Group isn't too worried about a drastic loss of confidence in the railways, pointing out that in Europe the state-backed rail networks are more overmanned than BR.

"How much longer can the French, Germans and Italians go on pouring money into these services," says Clarke. "We are ahead of the game in that we are having our pain now. The long-term prospects are very good."

Although Clarke hopes that the dispute will have a cleansing effect on rail freight efficiency, resulting in a less vulnerable industrial environment for freight users, she admits that its timing is damaging the emerging intermodal operators.

"I feel sorry for the intermodal operators who have had to face Channel Tunnel delays and have not been able to get on with building up their customer base," he says. "They just get their services going and start off really well and then they get clobbered by something like this."

Rumours of government interference in the negotiation process and the adamant stance of Railtrack's management has done nothing to reassure prospective buyers of the state-owned company that BR's track and signalling systems are in safe hands.

The Rail Freight Group has high hopes for the privatised railways, but the strikes only serve to highlight the negative aspects of rail freight, says Clarke.

"It's very disappointing to have something like this happening just when you are trying to change the image of the railways," she says. "Allowing private operators to run services will mean that they are more tailored to the customer's requirements. The Channel Tunnel has shown it can do very fast transits and can be reliable. The last thing you want is an old-fashioned strike which disrupts everything again because it just reinforces a lot of people's bad perceptions about the railways."

Clarke blames the Government's failure to improve rail infrastructure for the weaknesses which the dispute has highlighted: "The Government doesn't value the railways nearly highly enough," she says. "There have been moves in the past year or so to cut back on the roads programme and there has been a lot of talk from the DoT about getting more freight on the rail system, but it hasn't yet been translated into concrete measures which would produce results."

This view is echoed by Roger Sheddick of The Sheddick Group, which runs about 90 trucks internationally. He is cynical about the politicians' motives: "The politicians are using rail freight as a red herring OK, we can double the amount of freight on the railways but it still doesn't mean we can stop building roads. It's not freight we need to get off the roads it's people. When you sit on the M25, it's not trucks which are blocking it up, it's cars," says Sheddick.

His company is not picking up much business from the dispute at the moment because Sheddick believes that people are still struggling through while business is quiet during the holiday period. "Industrial output is down at the moment and that is having a calming effect," he says. "I am sure we are doing some work which would normally go by rail, but not in any huge volume. But if we have a few more of these five-day jobs it could start to have some effect then."

The Sheddick Group is typical of many British hauliers who view rail freight with some suspicion. Although the company does make some crossings through the Channel Tunnel, it is sticking mainly to the ferries.

"Unless someone puts a huge amount of money into building up the rail infrastructure the big move to rail freight is just not going to happen," says Roger Sheddick. "The intermodal systems are suffering. They are losing their viability when they say they can get to wherever it is in 36 hours, but they can't if there is a strike. It's not a good time for people launching those kind of services because we are all a bit sceptical about rail mainly because of fear of strikes in the Chunnel so this is really bringing it home to roost."

But fears that freight users which have found temporary ways round the one-day strikes will defect to road for good are exaggerated, says Jeff Miles of The Potter Group. His company operates two 70-acre rail terminals , one in Ely, Cambs and the other in Selby, North Yorks, handling around 200,000 tonnes of goods per year including stone, minerals and foodstuffs in conventional wagons.

"It is causing some inconvenience— bunching of trains and some additional overtime working but the stuff is getting through at the end of the day" says Miles. "It is damned inconvenient and I wish they would sort out their differences, but to us as terminal operators the cargo is coming through, it is just that the pattern has changed."

TI by Paul Newman