FORD D1000 YORK 28-TON-GROSS ARTIC

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 51

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE move of medium-weight goods-vehicle manufacturers into

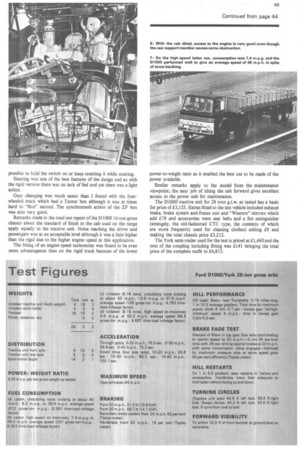

the maximum-gross class is logical as plating will prevent 8tonners and the like from being operated at above the designed weight. But while most of these makers have limited their entry into the higher-weight group to the previous legal maximum of 24 tons, Ford has gone further and in the latest D1000 range offers a tractive unit for operation at up to 28 tons gross.

A road test report of the D1000 16-ton-gross four-wheeler appeared in COMMERCIAL MOTOR (May 26) and that vehicle put up an impressive performance and gave very good fuel consumption and braking figures. The tractive unit version also performed very well and gave acceptable consumptions and acceleration times for a vehicle in its class but braking was not up to standard, although this could have been due to some maladjustment; on the handbrake tests only one side of the driving axle appeared to be doing any work: the tyres were leaving heavy marks as compared with none from those on the other side.

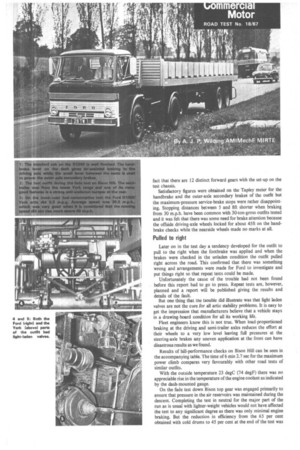

The tractive unit was not quite so pleasant to drive as the rigid due to some bounciness at the front on ridged road surfaces but against this the gear change was easier and the comfort of the seats and so on was to the same high standard.

Higher rated engine Apart from the shorter wheelbase, the main difference between the D1000 tractive units and the rigid versions is that the former have a higher rated version of the Cummins V8 diesel—maximum speed is increased from 3,000 to 3,300 r.p.m. and output from 162 b.h.p. net to 177 b.h.p. net although the maximum net torque is the same at 318 lb. ft. but at 1,900 r.p.m. as against 1,800 r.p.m.

There are 24and 28-ton tractive unit models and both have this higher-powered engine but whereas the higher-weight chassis has a ZF six-speed box as standard this is the alternative to the Turner five-speed unit in the 24-ton chassis, this gearbox being the standard in D1000 four-wheeled truck chassis.

The 28-ton tractive unit also has more brake lining area than the 24-ton model, it has larger tyres and is only available with the heavier-capacity Eaton 19800 two-speed axle; a single-speed axle is not available on this model.

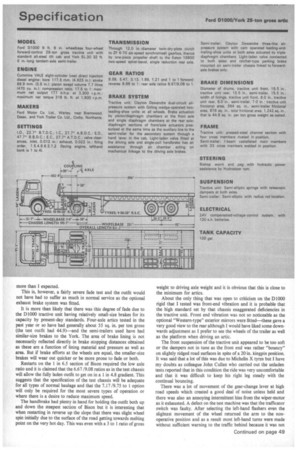

An important difference between the rigid and tractive units is in brakes, although the same types of actuating units are used at the wheels.

On the rigids, the secondary system is given by the diaphragm sections of the piston /diaphragm chambers at the front axle being pressurized at the same time as the handbrake-assistance diaphragm.

But on the tractive units there is a separate control for the secondary system which powers the front brakes and the auxiliary line to the semi-trailer. This is a small handbrake-type lever to the left-hand side of the driver's seat, the single-pull handbrake on the dash being used only for applying the driving axle brakes.

A light-laden valve is standard at the driving axle of D1000 tractive units (and a short wheelbase tipper) and this reduces the pressure applied .to the brakes there in part-load and unladen conditions to reduce the chance of wheel locking and resultant loss of directional control. Similar equipment was fitted to the York semi-trailer used for the test which was from the latest York SL range introduced only a short time ago.

For the tests, the semi-trailer platform was loaded more or less evenly with concrete blocks weighing 18 tons 16.5cwt which with three men in the cab made the gross weight just on the 28 tons for which the model is designed.

The area used for the test was the usual one south of Luton. As will be seen from the results table the acceleration times put up by the D1000 were quite good for a chassis with a power-to-weight ratio of only 6.32 b.h.p. per ton. The times for through-the-gears runs are above average for an artic in this class and a help in producing this result was the well-placed gear ratios in the ZF gearbox.

Direct-drive accelerations were checked with the lower of the ratios in the rear axle engaged and the times here were reasonable; there was a lot of roughness from the engine until 15 m.p.h. was reached.

Unlike results with the D1000 rigid, fuel consumptions returned by the artic turned out to be just about acceptable. Better figures have been given by 30-ton artics on previous road tests although in the test vehicle's favour was the fact that very good average speeds were obtained—in spite of a considerable amount of baulking on the motorway by other traffic.

Soon hack to maximum It was commendable that after being slowed by other vehicles the D1000 soon got back to its general running speed in the region of 60 m.p.h. The minimum speed on the southern stretch of the circuit between A6 and A4I47 junctions was 42 m.p.h. while on the return stretch the severe gradient north of A5 intersection brought it down to 36 m.p.h. Other vehicles in this class that have been tested are usually brought to a much slower speed—around 30 m.p.h.—on this particular gradient.

On the motorway later in the day the speedometer was checked and found to be accurate at all speeds and maximum speeds in the gears were checked. These were 4, 9, 15, 24, 36 and 44 m.p.h. with low axle ratio and 6, 11, 20, 32, 50 and 64 m.p.h. with high ratio. These figures show the even spacing of the ratios and the fact that there are 12 distinct forward gears with the set-up on the test chassis.

Satisfactory figures were obtained on the Tapley meter for the handbrake and the outer-axle secondary brakes of the outfit but the maximum-pressure service-brake stops were rather disappointing. Stopping distances between 5 and 8ft shorter when braking from 30 m.p.h. have been common with 30-ton-gross outfits tested and it was felt that there was some need for brake attention because the offside driving-axle wheels locked for about 45ft on the handbrake checks while the nearside wheels made no marks at all.

Pulled to right

Later on in the test day a tendency developed for the outfit to pull to the right when the footbrake was applied and when the brakes were checked in the unladen condition the outfit pulled right across the road. This confirmed that there was something wrong and arrangements were made for Ford to investigate and put things right so that repeat tests could be made.

Unfortunately the cause of the trouble had not been found before this report had to go to press. Repeat tests are, however, planned and a report will be published giving the results and details of the fault.

But one thing that the tsouble did illustrate was that light laden valves are not the cure for all attic stability problems. It is easy to get the impression that manufacturers believe that a vehicle stays in a drawing-board condition for all its working life.

Fleet engineers know this is not true. When load-proportioned braking at the driving and semi-trailer axles reduces the effort at their wheels to a very low level leaving full pressures at the steering-axle brakes any uneven application at the front can have disastrous results as we found.

Results of hill-performance checks on Bison Hill can be seen in the accompanying table. The time of 6 inM 2.7 sec for the maximum power climb compares very favourably with other road tests of similar outfits.

With the outside temperature 23 degC (74 degF) there was no appreciable rise in the temperature of the engine coolant as indicated by the dash-mounted gauge.

On the fade test down Bison top gear was engaged primarily to ensure that pressure in the air reservoirs was maintained during the descent. Completing the test in neutral for the major part of the run as is usual with lighter-weight vehicles would not have affected the test to any significant degree as there was only minimal engine braking. But the reduction in efficiency from the 65 per cent obtained with cold drums to 45 per cent at the end of the test was more than I expected.

This is, however, a fairly severe fade test and the outfit would not have had to suffer as much in normal service as the optional exhaust brake system was fitted.

It is more than likely that there was this degree of fade due to the D1000 tractive unit having relatively small-size brakes for its capacity by present-day standards. Four-axle artics tested in the past year or so have had generally about 55 sq. in. per ton gross (the test outfit had 44.9)-and the semi-trailers used have had similar-size brakes to the York. The area of brake lining is not necessarily reflected directly in brake stopping distances obtained as these are a function of lining material and pressure as well as area. But if brake efforts at the wheels are equal, the smaller-size brakes will wear out quicker or be more prone to fade or both.

Restarts on the 1 in 6.5 section of Bison required the low axle ratio and it is claimed that the 6.67 /9.08 ratios as in the test chassis will allow the fully laden outfit to get on in a 1 in 4.8 gradient. This suggests that the specification of the test chassis will be adequate for all types of normal haulage and that the 7.17 /9.75 to 1 option will only be required for the most severe types of operation or where there is a desire to reduce maximum speed.

The handbrake had plenty in hand for holding the outfit both up and down the steepest section of Bison but it is interesting that when restarting in reverse up the slope that there was slight wheel spin initially due to the surface of the road getting towards melting point on the very hot day. This was even with a 3 to 1 ratio of gross weight to driving axle weight and it is obvious that this is close to the minimum for artics.

About the only thing that was open to criticism on the D1000 rigid that I tested was front-end vibration and it is probable that the high standard set by that chassis exaggerated deficiencies in the tractive unit. Front end vibration was not so noticeable as the optional "Western-type" exterior mirrors were fitted-these gave a very good view to the rear although I would have liked some downwards adjustment as I prefer to see the wheels of the trailer as well as the platform when driving an artic.

The front suspension of the tractive unit appeared to be too soft or the dampers not in tune as the front end was rather "bouncy" on slightly ridged road surfaces in spite of a 20 in. kingpin position. It was said that a lot of this was due to Michelin X tyres but I have my doubts as colleague John Cullen who carried out the unladen tests reported that in this condition the ride was very uncomfortable and that it was difficult to keep his right leg steady with the continual bouncing.

There was a lot of movement of the gear-change lever at high road speeds which created a good deal of noise unless held and there was also an annoying intermittent hiss from the wiper-motor as it exhausted. A defect on the test machine was that the trafficator switch was faulty. After selecting the left-hand flashers even the slightest movement of the wheel returned the arm to the nonoperative position and as a result most left-hand turns were made without sufficient warning to the traffic behind because it was not

possible to hold the switch on or keep resetting it while steering.

Steering was one of the best features of the design and as with the rigid version there was no lack of feel and yet there was a light action.

Gear changing was much easier than I found with the fourwheeled truck which had a Turner box although it was at times hard to "find" second. The synchromesh action of the ZF box was also very good.

Remarks made in the road test report of the D1000 16-ton-gross chassis about the standard of finish in the cab used on the range apply equally to the tractive unit. Noise reaching the driver and passengers was at an acceptable level although it was a little higher than the rigid due to the higher engine speed in this application.

The fitting of an engine-speed tachometer was found to be even more advantageous than on the rigid truck because of the lower power-to-weight ratio as it enabled the best use to be made of the power available.

Similar remarks apply to the model from the maintenance viewpoint; the easy job of tilting the cab forward gives excellent access to the power unit for maintenance.

The D1000 tractive unit for 28 tons g.t.w. as tested has a basic list price of £3,125. Extras fitted to the test vehicle included exhaust brake, brake system anti-freeze unit and "Western" mirrors which add £78 and accessories were seat belts and a fire extinguisher (strangely, the old-fashioned CTC type, the contents of which are more frequently used for cleaning clothes) adding £9 and making the total chassis price £3,212.

The York semi-trailer used for the test is priced at £1.460 and the cost of the coupling including fitting was £141 bringing the total price of the complete outfit to £4,813.