A Ready Reckoner of Charges for the Hire of Tipping

Page 46

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Lorries to Municipal Authorities, Including Special Provision for the Higher Costs of Such Vehicles

Tonnage Rates for Tippers

TURNIT!IG from fixed-body lorries to tippers in this compilation of municipal haulage rates, the first thing to note is that the basic coststhat is to say, the fixed costs and the running costsare higher than those for ordinary lorries. Actually, taking average figures for vehicles of capacities of 2 tons to 5 tons inclusive, the increase in fixed costs of tippers as compared with fixed-body lorries is about 6 per cent., and the increase in running costs 14 per cent. The average overall cost considered in respect of a minimum weekly mileage is aboat 10 per cent.

A point whi,..th arises is that, as the percentage increase is greater in the running costs than in the

fixed costs, the disadvantage of the tipper, as against the ordinary lorry, is that the comparative cost of operation rises with the weekly mileage.

The advantage of the tipper, of course, which can sometimes be set oil against its increased cost, is the saving of time at the unloading end of every journey. At the loading end there is not, as a general rule, much difference. With any vehicle, when loading is by chute, it is usual to allow half an hour to cover loading time and delay. For unload lag, an average time of a quarter of an hour can be taken for tippers of all sizes between the limits previously mentioned. • With fixed-body lorries, as I showed in the previous article, that time varies from a quarter of an hour in the case of a .2-tonner to half an hour with a 5-tonner. The total terminal delays, therefore, whilst they remain constant at three-quarters of an hour for a tipper, begin at three-quarters of an hour for a 2-tonner, and rise to art hour for a 5-tonner with a fixed body.

In the case of heavier loads, therefore,. there is an advantage in the saving of time, when using a tipper, which should offset the increase in the basic cost. That is the case in respect of short leads, but as the lead distance lengthens, the greater running cost of the tipper is more evident, and the saving in cost, because of the slightly reduced time needed per trip, is thus lost. This is clearly exemplified in the figures given in Tables VII to X.

There should, however, still be some slight advantage remaining to the operator who uses tippers, because with such quick turnround it is frequently possible to work in an extra journey per day, thus increasing the opportunity for profit-making.

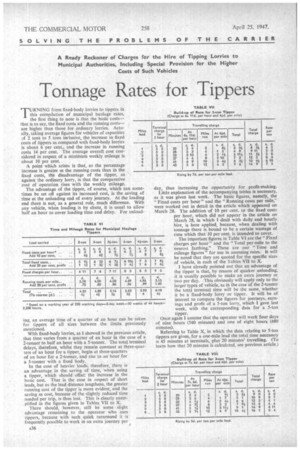

• Little explanation of the accompanying tables is necessary, as it was given last week. The basic figures, namely, the "Fixed costs per hour" and the "Running costs per mile," were worked out in detail in the article which appeared on March 28. The addition of 10 per cent, to the fixed costs per hour, which did not appear in the article on March 28, in which I dealt with daily and hourly hire, is here applied, because, when dealing with tonnage there is bound to be a certain wastage of time which that 10 per cent. is intended to cover.

The important figures in Table VI are the "Fixed charges per hour" and the "Total per-mile to the neare-t farthing." These are our "Time and mileage figures" for use in assessing rates. It will be noted that they are quoted for the specific sizes of vehicle, in each of the Tables VII to X.

I have already pointed out that an advantage of the tipper is that, by reason of quicker unloading, it is usually possible to make an extra journey or two per day. This obviously will apply only to the larger types of vehicle, as in the case of the 2-tonner the total terminal time will be the same, whether it be a fixed-body lorry or tipper. it will be of interest to compare the figures for journeys, earnings and profit of a 5-ton lorry, which I gave last week, with the corresponding data for a 5-ton tipper.

Once again I assume that the opeiator will work four days of nine hours (540 minutes) and one of eight hours (480 minutes).

Referring to Table X, in which the data relating to 5-ton tippers are given, for a one-mile lead the total time necessary is 45 minutes at terminals, plus 20 minutes' travelling. (To learn how that 20 minutes is calculated, see previous article.) In a nine-hour day we shall be able to run only tight journeys of 65 minutes each, with a loss of 20 minutes per day; in the eight-hour day, only seven journeys will be possible, with a further loss of 25 minutes. The total number of journeys per week is 39, which compares with the 34 journeys calculated in the previous article as being practicable with a fixed-body lorry, The revenue from 39 journeys at 1 ls. 2d. each is £21 15s. 6d. The net profit is one-sixth of that, which is £3 12s. 7d. per day, comparing with £3 10s, per day with a normal 5-ton lorry.

The reason why there is not a greater profit with a tipper " is the loss of 105 minutes per week, which is practically , sufficient to complete an additional one-and-a-half journeys. This loss of time is really serious; in the case of a two-mile lead it is even worse than with a one-mile lead.

The total time of the round journey on a two-mile lead is shown in the tables as 45 minutes for terminals, plus 28 minutes for the journey-73 minutes in all. That figure. divided into 540 minutes, gives seven journeys, with a wastage., of 29 minutes per day, and during the eight-hour day, only six• journeys, with a wastage of 42 minutes. The total wastage during the week is thus 158 minutes, which is ample time for a further couple of journeys.

The total number of journeys per week amounts to 34, as against 29 with a normal lorry. The revenue is 34 times 13s. 5d., which is £22 16s. 2d., and the net profit £3 16S„ as against £3 10s.

When we come to the three-mile lead there is no waste of time, As a matter of fact, in order to complete seven journeys in a day, we should need 546 minutes, so that six minutes will have to be made up somewhere during the day in order to do that amount of work. It is reasonable, however, to expect that that will he done, so that we shall have seven journeys per day for four days and six

on the fifth, a total of 34 for the week, compared with 29 with a fixed-body lorry. The revenue at 15s. 3d. for the journey is £25 18s. 6d., and the net profit £4 6s. 5d., instead of £3 17s. 9d.

Turning now to the five-mile lead, for which the time necessary is 86 minutes, it is clear that the number of journeys will be six on the nine-hour day and five in the eighthour day, with a wastage of 24 minutes per day in the former case and as much as 50 minutes in the latter, a total wastage of 146 minutes-practically time to complete two further journeys.

Nevertheless, 29 journeys are possible in the week,. as compared with 25 with a normal lorry. The revenue is 29 times 18s. 7d., which is £26 18s. lid., and the profit practically £4 10s., as compared with £3 17s.

There is no point in this article in making comparisons with the figures which I gave for a 2-ton lorry in the previous article, because, as the journey times are the same, no saving will accrue as the result of working in an extra journey. The cost of the tipper is greater and there will be, on that account, a small increase in weekly profit; not enough, however, to be worth calculating in detail.

The journey times quoted in this and the previous article are not tos•be regarded as being in any way constant. Differences in conditions may diminish or extend them. A quicker turnro,und,. the provisionof adequate loading facilities and the absence of need for queueing, easy unloading and unconge-sted roads, all combine to reduce the overall time per trip and make possible more journeys per day. To persuade the drivers to co-operate may improve matters, and usually the way in which this is done is by offering an inducement to them to put their backs into the job and endeavour to bring in an extra load. Opinions vary as to ,the wisdom of this system, and it is often objected that excessive speeding, dangerous driving, and other excesses arise from this practice.

Often, I have been told, drivers are paid an extra-halfcrown for each journey over and above the minimum. As regards profit-making only, such a course is not Worth while. It can be justified only when it is desirable to move the maximum possible tonnage per week.

As showing the economical aspect of the matter, take the case of a one-mile lead with a 5-tonner, and assume that as the result of-being paid an extra half-crown per day, the driver makes nine journeys per nine-hour day and eight during the eight-hour day, a total of 44 journeys per week. The revenue is 44 times 1 ls. 2d. (£24 1 Is 4d. per week), showing a net profit of £4 is. 11d. From that sum must be deducted the eittra 12s. 6d. cif wages ,paid to the driver, bringing the profit down to £3 9s: 5d., as compared with £3 12s, 7d. -when only eight and seven journeys respectively were run. On that basis, therefore, the method of giving a half-crown bonus is shown to be uneconomic.

The certain way of making the week's operations More profitable is to work a reasonable mount of overtime each day-say about l hours. The problem of assessing the potential profits involves a special calculation. As a preliminary to making that calculation, reference must be made first of all to the basic figures for cost per hour and cost per mile, which will be found in Table VI.

The two items we require are those entitled "Total fixed costs" and " Running costs per mile.In the case of the 5-tonner. for example, the figures are total fixed costs at 7s. 8id. per hour, and

running costs per mile, 5.15d. per mile. Working approximately 1 hours' overtime each day, a total of, say, eight hours in the week, it should be easy, over a one-mile lead, to increase the number of journeys to 10 per nine-hour day and nine per eight-hour day, making a total of 49 journeys per week. The revenue from those 49 journeys at I ls. 2d.

per journey totals £27 7s. 2d. We must now ascertain the cost to obtain the net profit.

Turning again to Table VI and referring to that figure of 7s. 81d. per hour, it should be noted that in 44 hours all the fixed costs, with the exception of wages, are liquidated for the whole of the week.

The basic wage for the driver of a 5-tonner in a Grade l area is £4 18s, per week. For his overtime he will be paid at the rate of time-and-a-quarter, and the amount is. 2s. 9-Nd. per hour. Eight hours at that rate is equivalent to LI 2s: 31c1. The fixed costs, inclusive of the driver's ordinary wage, comprise the total of 7s. 81d. times 44 hours, which is £16 9s. 2d. Add the payment for overtime, and the result is £17 us. 50. as the total of fixed costs for that week, including the expenditure involved in overtime.

The mileage covered during the week is 98 at two miles per journey for 49 journeys, and the cost at 5.15d. per mile is £2 2s. 7d. The total expenditure during the week is, therefore, £19 14s. Id, As the revenue is £277s. 2d., the net profit is £7 13s. Id., which demonstrates that, when practicable, overtime is profitable alike to the driver and the operator. S.T.R.