THE SAME FOR LESS

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

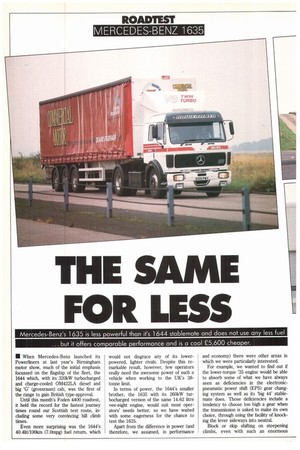

Mercedes-Benz's 1635 is less •owerful than it's 1644 stablemate and does not use an less fuel ... but it offers corn•arable •erformance and is a cool £5,600 cheaper.

• When Mercedes-Benz launched its Powerliners at last year's Birmingham motor show, much of the initial emphasis focussed on the flagship of the fleet, the 1644 which, with its 320kW turbocharged and charge-cooled 0M422LA diesel and big `G' (grossraum) cab, was the first of the range to gain British type-approval.

Until this month's Foden 4400 roadtest, it held the record for the fastest journey times round our Scottish test route, including some very convincing hill climb times.

Even more surprising was the 1644's 40.41it/100km (7.0mpg) fuel return, which would not disgrace any of its lowerpowered, lighter rivals. Despite this remarkable result, however, few operators really need the awesome power of such a vehicle when working to the UK's 38tonne limit.

In terms of power, the 1644's smaller brother, the 1635 with its 260kW turbocharged version of the same 14.62 litre vee-eight engine, would suit most operators' needs better, so we have waited with some eagerness for the chance to test the 1635.

Apart from the difference in power (and therefore, we assumed, in performance and economy) there were other areas in which we were particularly interested.

For example, we wanted to find out if the lower-torque '35 engine would be able to absorb some of what we have always seen as deficiencies in the electronicpneumatic power shift (EPS) gear changing system as well as its 'big 44' stablemate does. Those deficiencies include a tendency to choose too high a gear when the transmission is asked to make its own choice, through using the facility of knocking the lever sideways into neutral.

Block or skip shifting on steepening climbs, even with such an enormous amount of torque of the 1644, proved uncomfortable at times so the opportunity to test the EPS-equipped 1635 also offered a chance to sound out the merits (or otherwise) of M-B's controversial transmission.

By virtue of its smaller L-type doublesleeper cab and the lack of a chargecooling system, the 1635 is a little lighter than the 1644, but the 370kg difference is of little significance where the vehicle's payload potential is concerned.

• PERFORMANCE

The 1635 could hardly be said to be lacking in punch, unless compared with such massively torquey engines as the 1644, Scanias P142 or the European torque-topper, the Iveco Ford Turbostar.

A look at the turbocharged 0M442A's performance curves shows it to have a steep power rise from 800rpm, with an impressive 1, 600Nm (1,1801bft) torque plateau that runs from 1,000 to 1,500 rpm.

In addition, its specific fuel consumption curve hangs below 200g/kW/hr for much of that engine speed range.

While all of this promises a fast, economic output, an early indication of a vehicle's performance is usually obtained over the test tracks at MIRA.

In this kind of power bracket, there is generally little to choose between models, and although the ZF Ecosplit-based transmission has a slower gear change than most, its acceleration times were impressive.

Using the kick-down facility which overrides the engine speed limiter, it was marginally quicker through the gears than the Daf FT3600 Ati (CM 4 January 1986) and recorded similar times to MAN's 19.361 (CM 3 November 1984).

From 0-80km/h it was five seconds behind the M-B 1644, but slipped back further in the short burst from 48 to 80km/h, due to the wide difference in their outputs.

Even a 'mere' 260kW has to be handled carefully and on the test hills, despite a certain amount of caution, it failed to meet its 29% gradeability rating. This was largely because of a park brake that failed to hold on the 25% grade and was only just adequate on the 20% hill.

On the road the sheer flexibility of the quiet-running vee-eight and its matched driveline provided journey times that make it among the best of our most recently tested models.

For general A road work, eighth low is a perfectly adequate gear to use, allowing the engine to run exceptionally smoothly at 1,100rpm. With maximum torque on tap it can accelerate to 80km/1-1 effortlessly before top gear is selected.

Over Beattock the 1635 pulled strongly at the 80km/h maximum speed and but for one congested stretch of contraflow it would have powered over with just one split from top.

Running at the maximum permitted speed on motorways is equally effortless — indeed great care has to be exercised to hold it back. Here the twin exhaust brakes, which work surprisingly well, play an important part.

IE FUEL CONSUMPTION

At 96km/h the engine pulls the 0.85:1 top gear easily at 1,650rpm, which takes it over the 200g/kW/hr figure and away from its most economic region.

As our operational trial results suggest, it excels both in terms of fuel economy and trip times over dual-carriageways and motorways.

Overall, its fuel consumption figure of 40.5lit/100km (6.97mpg) in favourable weather conditions, gives it a high rating for trucks in the 260kW category pulling 38 tonnes_ Naturally enough, severe terrain takes its toll on both fuel and times, but this can vary to a large extent depending on the driver's familiarity with and use of the 1635's EPS gearshift system.

• EPS GFARCHANGING

Although by now we are reasonably familiar with the EPS arrangement, a driver needs to be constantly aware that the short, stumpy gear lever is in fact an electrical switch which can be actuated very easily indeed — provided the clutch movement is sufficient to activate the sensor switch that ensures gear shaft synchronisation. A mere two-fingered pressure is all that is required.

Using the EPS also calls for a change in driving discipline and an acceptance that the system will not change gear any faster than the ZF Ecosplit on which it is based. In practice it even seems slower, particularly when block shifting over very hilly regions. It is very important to hold down the clutch long enough to allow the pneumatics time to go through the change motions.

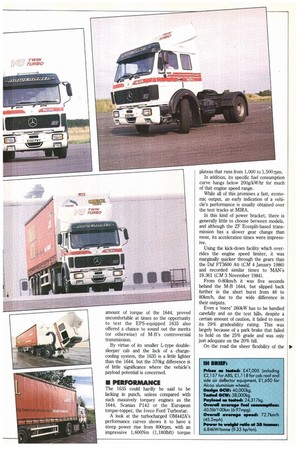

On the notorious 14% (1-in-7) Redesdale and Kiln Pit hill climbs, where the rapidly steepening ascents called for a series of block changes, the dilatory nature of the EPS was exposed. It also emphasised the enormous advantage offered by the 1644's massive amount of power and torque in such cases: earlier this year it sailed up these hills in midrange gears. The 14.6 litre vee-eight's manifolds were revised two years ago to give it better breathing. Access for maintenance is adequate but the engine looks as if it has out-grown the chassis.

Block changes can only occur at or below 1,050rpm but on a long steep grade, two gears are not always sufficient, so another is needed and maybe one more as the vehicle slows.

On Redesdale the truck stopped altogether, and on a smooth surface without a cliff lock some wheel spin was experienced. There it was simply a case of bottom gear and a gentle throttle pressure until there was sufficient speed and distance to change up.

The EPS also allows the driver to use the system to select a gear appropriate to road and engine speed. This entails moving the lever left (into neutral) and then forward or back using the clutch.

On severe gradients, it was deemed to be unwise to use this method as the EPS invariably seems to opt for too high a gear. Quite simply the EPS system's major strength is that it offers the driver a more relaxed driving style and under extreme conditions early selection of lower gears should prevent any unpleasant situations.

• HANDLING At 7,053kg the fully equipped and fuelled 1635 is slightly lighter than the outgoing 1633 model. Three-leaf parabolic springs have been adopted at the front which, as well as saving on unladen weight, contribute towards superb road holding.

Mercedes-Benz fits anti-roll bars front and rear which also play an important Part.

Several sections of our Scottish route feature the type of rough road surfaces that stretch a cab's suspension close to its limit, yet throughout the test the Mercedes fully-sprung cab gave an excellent ride with hardly a trace of excessive movement and a minimum of roll, even on the more awkward bends.

The 1635 is also one of the quietest vehicles we have tested, with noise levels that never rose above 73dB(A) in the cab, even on the climbs over Shap and Beattock.

Running down from the summits of these hills, the exhaust brake was an effective supplement to the service brakes, and the optional Mercedes/Wabco anti-lock and the Grau Girling Skidchek on the Crane Fruehauf test trailer performed extremely well.

As on the 1644 tested previously, the 1635's ABS warning light stays on, betraying the absence of an electrical interlock between the unit and trailer.

• CAB COMFORT The 1635's all-steel L-type sleeper cab is well up to Mercedes-Benz's usual high standard of driver comfort in terms of heating and effective noise and thermal insulation. Nonetheless it still fails to provide a simultaneous supply of fresh air to the driver and hot air in the footwell.

Mercedes' air deflector seems to work efficiently and the tinted glass effectively removes any glare, but the darkened sunvisor is rather too dark and has an adverse effect on the driver's field of vision, particularly where long down-hill runs meet with a sharp climb. In this case the driver has to lean forward to see if traffic is coming down the hill towards

• SUMMARY

In Britain Mercedes-Benz does not offer a manual option to EPS and, judging by the sales figures, few operators want one, because registration figures for its heavy artic units for the first eight months of this year were up by 33% over 1986. Sales of the 1635 are almost twice those of its 1633 predecessor.

Our operational trial suggests that in the 1635 the EPS does help to provide an easier, almost leisurely driving environment, but this praise must be restrained because of its limitations and vagaries.

In spite of its hefty 260kW output, the torquey 0M422A is quite an efficient engine and, with the 1635's matched driveline, gives similar fuel economy and journey times to its more powerful 1644 stablemate — for 25,600 less.

At 242,080 for a standard 1635, the cost of EPS has been competitively packaged in what has been a smooth transition from manual changes — unlike Scania, which has not had the same success with its optional CAG system • by Bryan Jarvis