After 10 years, the bitter criticism of the RTITB is dying down, and the training benefits becoming evident

Page 232

Page 233

Page 234

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

OPERATORS GET WISE

MENTION the Road Transport Industry Training Board at an gathering of hauliers and you will get a variety of reactions Yet had you done so only a few short years ago, the reaction would have probably been unanimous and less tha complimentary.

The change reflects the difference in attitudes to imposet training now evident throughout the industry, as it adopts a more professional approach to road haulage.

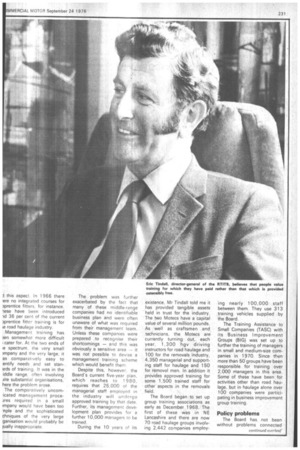

It would be idle to pretend that the Board was any less than unpopular when it was set up 10 years ago, and this was acknowledged by Eric Tindall, its director-general, when I asked him what he thought the progress made in the past ten years.

He told me that objections to the Board's activities arose mainly from three sources. There were those who saw no merit at all in formal training and others who realised its value, did not wish to contribute financially but were quite prepared to poach staff from those who had.

Prickly companies

Perhaps the most prickly were the companies who already had training schemes. They thought that the advent of the Board was a jolly good thing for other people, but their sensitivity was outraged when the extent and standard of their training was questioned.

Apart from increasing the quantity of training, the Board was concerned with improving the quality from the outset, Mr Tindall explained. When the Board began to function, there were no accepted standards of training and, perhaps more important, no assessment of the industry's future needs for trained staff.

Because there was a multiplicity of things to be done, including the recruitment of suitably qualified staff, it was a couple of years before the Board began to operate in earnest. It was, possibly, not till a further two years had elapsed that the results of those opera, tions began to become appar. ent. In the interim, the Boarc encountered its greatest perioc of criticism.

From about 1970 onwards as the value of formal traininc began to become apparent tc those who were prepared t( recognise it, the Board's imag( has gradually changed, here an still those who regarc themselves as its implacabli opponents and operators whc resent having to pay a levy though it amounts only to on per cent of the annual payroll.

Despite opposition, thi Board has made significan advances in increasing traininl and improving standards. Per haps the most dramatic of the& has been in driver training.

Previously this had largel. consisted of the trainee lea rnmn!

his trade by accompanying a experienced driver and pickin. up his trade as he went alonc, There was no guarantee the the experienced man was eve teaching the trainee a good an safe way to do the job.

The imposition of the hg driving licence, certainly fr new drivers, and the evc increasing value of vehicles an loads, however, made formi training imperative.

Since 1966, the Board hr not only improved the quality c driver training by laying dow acceptable standards but he also increased the numbei from the 2,500 a year thE prevailing to 16,000 a year i 1975/76

Informed staff

Larger and more sophistica ed vehicles need bettE informed staff to maintain thei and the Board has not neglec

I this aspect. In 1966 there 'ere no integrated courses for )prentice fitters, for instance. lese have been introduced -id 36 per cent of the current )prentice fitter training is for le road haulage industry.

Management training has ?.en somewhat more difficult cater for. At the two ends of le spectrum, the very small )mpany and the very large, it as •comparatively easy to entity needs and set stan)rds of training. It was in the iddle range, often involving Ate substantial organisations, here the problem arose.

The comparatively uncomicated management proceires required in a small impany would have been too -nple and the sophisticated chniques of the very large ganisation would probably be pally inappropriate.

The problem was further exacerbated by the fact that many of these middle-range companies had no identifiable business plan and were often unaware of what was required from their management team. Unless these companies were prepared to recognise their shortcomings — and this was obviously a sensitive area — it was not possible to devise a management training scheme which would benefit them.

Despite this, however, the Board's current five-year plan, which reaches to 1 980, requires that 25,000 of the managerial staff employed in the industry will undergo approved training by that date. Further, its management development plan provides for a further 10,000 managers to he trained.

During the 10 years of its existence, Mr Tindall told me it has provided tangible assets held in trust for the industry.. The two Motecs have a capital value of several million pounds. As well as craftsmen and, technicians, the Motecs are currently turning out, each year, 1,300 hgv driving instructors for road haulage and 100 for the removals industry, 4,350 managerial and supporting staff for haulage and 150 for removal men. In addition it provides approved training for some 1,500 trained staff for other aspects in the removals field.

The Board began to set up group training associations as early as December 1968. The first of these was in NE Lancashire and there are now 70 road haulage groups involving 2,442 companies employ

ing nearly 100,000 staff between them. They use 313 training vehicles supplied by the Board.

The Training Assistance to Small Companies (TASC) with its Business Improvement Groups (BIG) was set up to further the training of managers in small and medium-size companies in 1970. Since then more than 50 groups have been responsible for training over 2,000 managers in this area. Some of these have been for activities other than road haulage, but in haulage alone over 100 companies were participating in business improvement group training.

Policy problems

The Board has not been without problems connected with changes in the economy and Government policy. With the introduction of the Employment and Training Act 1973 it had to relate its plans to the provisions of that Act and the overall policy of the Training Services Agency.

In relation to the levy/grant scheme which the board had operated since its inception, exemption and levy rebate was added. Though it meant a fall-off in the level of activity of its field staff, the Board decided not to recruit additional staff for exemption assessment. Instead it used 37 of its existing field, staff who had to be retained for the purpose.

From October 1974 to March 1975, it received over 1,000 applications for exemption from the levy/grant scheme about 25 per cent of which were from organisations without any identifiable record of previous training and which did not submit any plans of training intention. Obviously they did not understand that exemption was intended to be an incentive to undertake training on their own behalf but thought that exemption implied a withdrawal from training altogether.

Of the remainder, those companies who were able to satisfy the Board that they had serious and comprehensive training schemes setting acceptable standards have gained exemption, reviewable every year, others have gained partial exemption where training area have reached the required standard and participate in the levy rebate arrangements where they do not.

This reflects the trend for companies to confine their training activities to their main interest, such as driver training in the road haulage industry, while providing little or no training for other occupations within the company.

The changes in the financial arrangements contained in the 1973 Act encouraged the Board to set up a service which it could sell on a commercial cost recovery basis. It therefore created the Operational Services Group which arranges courses and seminars for which a separate charge is made. During the six months trial period from October 1974 to March 1975, 170 inquiries for courses were received. Of these, 55 accepted and completed bringing in a revenue of over £20,000. A further 61 offers were made from the remainder and 24 accepted to the value of f.25,000.

The services offered by this group were previously supplied to the industry free of charge, Mr Tindall told me.

He stressed the efforts that the Board had made to identify itself with the industry it serves rather than occupying an ivory tower as it has often been accused.

The composition of the Board with long-serving representatives from employers, employees and the educational field as well as permanent Board staff has helped to further this aim. With such a Board, the policies adopted have obviously reflected the views and requirements • of all sides of road haulage.

lrn visits Moreover, Mr Tindall said, over one million visits to companies within the Board's scope have been made by its field staff.

Identification with the industry has been a maintained aim despite changes brought about by the 1973 Act so that the Board has been able to continue to further the particular needs and special problems it encounters without becoming involved in side issues.

Perhaps the greatest problem that the Board faces and which it has been plagued since it began to function is that it includes within its scope only about one third of people employed in road haulage. speaking of this Mr Tindall w referring to road haulage st employed by own-accou operators, the majority of who bear no part of the cost training such staff.

Though many own-accou operators come within t scope of other Training Board no part of their contributi • accrues to training for their ro transport staff anti, indee trained staff paid for by the roa haulage industry is frequent lost to them.

Despite all the Board efforts to remedy this situatio it has not been successful doing so.

Training in the road haulag industry has levelled off in th past two years as a result of th current economic recession bu said Mr Tindall, the Board ha, not fallen into the trap c complacency. He pointed DI. that the need for training was a great as ever because traine staff would be required quickl when the economy begins t recover, as it must.

It takes time to train an hg driver, for instance, and th driver wanted tomorrow woul not be available for at least couple of weeks if he had to b trained.

In the meantime, naturi wastage such as retirement an people leaving the industry fc other jobs who might nev( return constituted a reduction i the supply of trained staff whic would have to be made goo eventually.