Good Budgeting Kills

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

RATE-CUTTING

THE previous article disclosed what purported to be the operating 'costs, revenue and net profits made by a haulier running a 3-ton vehicle under an A-licence contract, hauling oil cake and, cattle feed. The figures related to six months of the year and were for a winter quarter and a spring quarter. The haulier, happy during the first quarter, was disturbed because in the second quarter his figures showed a loss.

L-had to point out to him that this was in part the result of taking on a contract without properly investigating the prospects, besides taking on a contract of a kind which is rarely satisfactory. He had quoted per tan of traffic and taken winter deliveries as a basis for his quotation, omitting to make provision for the fact that in the spring and summer the demand for this traffic would be comparatively small. so that at the rate quoted he was bound to make a loss.

There was more than that, however. I discovered that he had made that old familiar mistake of omitting provision for future expenditure on maintenance and tyres and had not made any allowance at all for overheads and contingencies.

The subject of this article is important; I pointed out, in relation to the fact that rate-cutting is again becoming prevalent. Off to a False Start

In this case the operator started'with a new vehicle, and during the 'six months under review his expenditure on repairs and tyres was practically nil. In consequence, his operating costs were comparatively low, and for the greater part of the six months he seemed to be making a profit.

In that article I demonstrated that for proper assessment of cost as a basis for rates, it is essential to budget for future expenditure, especially in such matters as maintenance and tyres.

In the end I was able to show that whereas over the six months' working his figures showed a profit of rather more than 128, in reality he was operating at a loss for that period of neatly £7, and that without taking into consideration his further expenditure in iespect of overheads or establishment charges and contingencies.

The office expenses are small," he said, "end. I don't need wages. My wages are the profits of the business."

"Let me go into this question of your own wages." 1 said. , " I understand that you have altogether four vehicles. 1 suppose you have quite enough to do finding work for these?"

"I should say 1 have. The ordinary eight-hour day does not apply to me!"

Wages for the Owner " Then you should certainly draw a definite amount out of profits as wages, and you cannot regard your enterprise itself as making a. profit until after your wages have been paid. That is one of the first principles-of business management, and no argument about paying yourself out of profits will affect it. At the very least you ought to draw £3 per week. But that is only a part of what 1 mean by.establishment charges."

I then picked up a copy of "Cost Recording Made Easy" (obtainable from the offices of "The Commercial Motor" at 2s. per copy). I turned to page 14 and showed him a schedule of establishment costs-which appears therein.

"Here," I said, " is a list of items of establishment costs. I want you to go through these with me and check up on your own expenditure as regards each one of them."

We went through the items together and argued them at considerable length. The results are shown in Table IV. and the outcome, indicating a total of £243 13s. per annum, was a big shock to this haulier friend of mine.

"You know." he said. "I " wouldn't have believed it possible."

c14 " It is not only possible," I said, " but I am quite sure

that we' have not accounted for everything. I should imagine the real total is nearer £343 13s. than £243 13s. However, we will let it go at that. Now," I said, "admittedly that £243 of establishment expenses is incurred in connection with the operation of a fleet of four vehicles. I don't suggest that we should debit the whole amount agaihst this one 3-tonner. The next thing we must do is to allocate that total in props proportion amongst the four vehicles that you have. What are the load capacities of the other three? "

" They are all 5-tonners."

Assessing Overheads Per Vehicle "In that case," I said, "you have actually the equivalent of 18 tons of payload in your fleet of four vehicles, and the proper way to assess, these overheads per vehicle is first of all to take out a figure per ton of payload, and we do that by dividing £243 I3s. by 18. That gives us £13 10s. per annum for each ton of payload, so that your 3-tonner -must carry three times that, which is 140 10s. per annum or roughly 16s. per week.

." That amount should have appeared in your statement of cost and it means that you have, in the 26 weeks for which you have presented the figures, omitted an item totalling £20 16s. In fact, therefore, your total loss has been, in round figures, £27 and not only the £7 at which we have assessed it up to now,

"In my view," I said, "you should go to the man with whom you made the contract, tell him that you have made a serious error, present him with some logical figures, for cost and show him what your charge ought to be, if you are going to make anything out of this contract. Whether you can persuade him to meet you or not is something I cannot foretell, but if he will not meet you, then the only thing you can do is terminate the contract as soon as possible.

"1 think perhaps the best thing we can do now is to get together and work out some really sensible figures for costs and charges.

"First of all your fixed charges. You have told me that your tax is £33 10s. per annum, which is approximately 13s. 6d. per week.

£11 4s. a Week Fixed Charges "Wages and drivers' insurances you have at £5 per week. For rent, £22 10s. per annum, which is 9s. per week; for insurance, £30 10s. 6d., which 1 will take as 12s. per week. Then comes the interest on the capital outlay involved in your vehicle, 6s.-; depreciation, again I will take your own figure, £2 per week, and finally this little item of establishment costs, 16s.; a total of £9 16s. You ought to make a .minimum of 15 per cent, profit on that, which is £1 8s., giving a total of £11 4s. per week."

Here he interrupted me: "But I !lave been making much more than that during most of the weeks I have been operating."

We have not finished yet." I said. "We have no figures down for running costs. The first of these is petrol. You said you were getting 10 miles to the gallon-and if, as I expect, you are paying Is. lid, per gallon for your fuel. that means that the cost per mile is 2.3d."

I worked his oil consumption out and showed that the cost was 0.3d. per mile.

"For tyres and maintenance. I suggest we rake the figures . already given to you, that is .5d. per mile for tyres and .9d. for maintenance. The total is 4d. per mile, but you must add 15 per cent. profit on that, which is .6d., so that your total charge will be 4.6d. per mile.

"Clearly," I said, "the total to be charged against running costs will vary each week according to the mileage, but as a

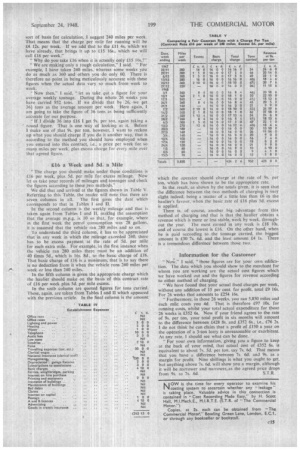

sort of basis for calculation, I suggest 240 miles por week. That means that the charge per mile for running will he £4 12s. per week. If we add that to the £11 4s. whichwe have already, that brings it up to 1:15 16s., which we will call £16 per week."

" Why do you take £16 when it is actually only £15 16s.?".

" We are making only a rough calculation," I said. "For example, I have taken 240 miles, whereas some weeks you do as much as 360 and others you -do only 60. There is therefore no point in being meticulously accurate with these fieures when the actual data vary so much from week to week.

" Now then," I said, "let us take gut a figure for your average weekly tonnage. During the whole 26 weeks you have carried 952 tons. If we divide that by 26, we get 36;1 tons as the average amount per week. Here again, I am going to take the figure of 36 tons as being sufficiently accurate for our purpose.

"If I divide 36 into £16 I get 9s. per ton, again taking a round figure. That is one way of looking at it. Before 1 make use of that 9s. per ton, however, I want to reckon up what you should charge if you do it another way, that is according to the method you should have employed when you entered into this contract, i.e., a price per week for so many miles per week, plus excess charge for every mile over that agreed figure.

£16 a Week and 5d. a Mile

"The charge you should make under those conditions is £16 per week, plus 5d. per mile for excess mileage. Now let its take your records of mileages and tonnages and check the figures according to these two methods."

We did that and arrived at the figures shown in Table V. Referring to this Table, the reader will note that there are seven columns in all. The first gives the dale which corresponds to that in Tables 1 and II.

In the second column is the weekly mileage and that is taken again from Tables 1 and 11, making the assumption that the average m.p.g. is 10 so that, for example, where in the first week the petrol consumption was 28 gallons. it is assumed that the vehicle ran 280 miles and so on.

'to understand the third column, it has to he appreciated that in any week in which the mileage exceeded 240, there has to be excess payment at the rate of 5d. per mile for each extra mile. For example, in the first instance when the vehicle ran 280 miles there must be an addition of 40 times 5d., which is 16s. 8d, to the basic charge of £16. That basic charge of £16 is a minimum, that is to say there is no deduction from it when the vehicle runs 240 miles per week or less than 240 miles.

In the fifth column is given the appropriate charge which the haulier should make on the basis of this contract rate of £16 per week plus 5d. per mile excess.

In the sixth column are quoted figures for tons carried. These, again. are taken from Tables I and II which appeared with the previous article. In the final column is the amount

which the operator should charge at the rate of 9s. per ton, which has been shown to be the appropriate rate, In the result, as shown by the totals given, it is seen that the difference between the. two methods of charging is very slight indeed, being a matter of a little less than £6 in the haulier's favour, when the basic rate of £16 plus 5d. excess is applied.

There is. of course, another big advantage from this method of charging and that is that the haulier obtains a revenue which is more or less stable, week by week, throughout the year. The most earned in any week is £18 10s. and of course the lowest is £16. On the other hand, when he is paid according to the tonnage carried, the biggest amount is £30 7s. 6d. and the least amount £4 Is. There is a tremendous difference between those two.

Information for the Customer

I said, "those figures are for your own edification. The data which you should show to the merchant for whom you are working are the actual cost figures which we have worked out and the figures for revenue according to either method Of charging.

"We have found that your actual fixed charges per week, without any addition of 15 per cent. for profit, total £9 16s. For 26 weeks that amounts to £254 16s.

" Furthermore, in those 26 weeks, you ran 5.850 miles and each mile, costs you 4d. That is therefore £97 10s. for running costs, whilst your total actual expenditure for those 26 weeks is £352 6s. Now if your friend agrees to the rate of 9s. per ton, your total profit in six months will amount to the difference between £428 8s. and £352 6s.. i.e., £76 2s. I do not think he can claim that a profit of £150 a year on the operation of a 3-ton lorry is unreasonable or exorbitant. At any rate, I should see what can be done.

"For your own information, giving you a figure to keep at the back of your mind, that actual cost of £352 6s. is equivalent to about 7s. 5d. per ton. say 7s. 6d. That means that you have a difference between 7s 6d. and 9s. as a margin for profit. Nine shillings is what you ought to get, but anything above 7s. 6d. will show you a margin, although it will be narrower and narrower, as the agreed price drops

from 9s. to 7s. 6d. S. T.R.

NOw Is the time for every operator to examine his costing system to ascertain whether any "leakage" is taking place. Valuable advice in this connection is contained in "Cost Recording Made Easy," by H. Scott Hall, M.I.Mech.E., M.I.R.T.E. (S.T.R. of "The Commercial Motor.")

Copies. at 2s, each can be obtained from "The Commercial Motor.," Bowling Green Lane, London, E.C.1. or through any bookseller or bookstall.

THE first British bus chassis to be equipped with servo-operated steering has been produced by Transport Vehicles (Daimler). Ltd., Coventry. and will be exhibited on the company's stand at the Commercial Motor Show Planned to meet the requirements of present arduous service conditions, the new vehicle, designated the Daimler C.V.D.650 chassis, incorporates also ,hydraulically operated servo hand-hrak-e and doorgear arrangements.

Designed primarily for overseas markets, the chassis, which has a wheelbase of 16 ft. 4 ins., accommodates an

8-ft.-wide 56-seater double-deck -body. The overall length is 27 ft. and the gross laderi weight 12 tons.

The power unit is a Daimler six-cylindered 19.6-litre direct-injection oil engine, which has the same general characteristics as the 8.6-litre model, but incorporates a number of new features. As in all Daimler engines. the foundation is an extremely _rigid support' for the crankshaft, and. on this has-been developed a unit to give the greatest power output consistent with reliability and freedom from vibration.

With a 5-in„ bdre and 5.5-in, stroke, the engine develops 120 b.h.p. at a governed speed of 1,700 r.p.m. and has a compression ratio of 15 to 1.. Maximum b.m.e.p. is 104 lb. per sq. in. at 820 r.p.m., the maximum torque being 445 lb.-ft. at 820 r,p.m. grooves; in preference to plating the cylinder liners The cylinder block is cast in close-grained alloy iron. and the renewable " push-in " dry liners are manufactured from Brivadium nickel cast iron. Twin detachable cylinder heatis'have inlet portsdesigned to promote' turbulence and avoid the necessity of screened inlet valves.

'Four-hole injectors spray into flat, elongated bowls. formed concentrically in the piston crowns, the centre of the bowl lying approximately on the axis of the spray. This allows for a spray length of more than the critical minimum of 1.1 ins.'

Vertical Valves Silicon-chrome-molybdenum valves are positioned vertically and the exhaust valves are faced with Brightray. The Brimocrome seats of the exhaust and inlet valves are renewable. The exhaust porting in the head is arranged to allow water passages round the injector boSses, and a high rate of directional flow is maintained by feeding the water into the head from the block through slotted caps. Water is delivered to the front of the cylinder block and pattern-circulated through the block and head to outlets on the off side of the head, thence to the flexible-joint Still-tube radiator. A by-pass thermostat is provided