SCANIA VABIS/BODEN 32-TON-GROSS ARTIC

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

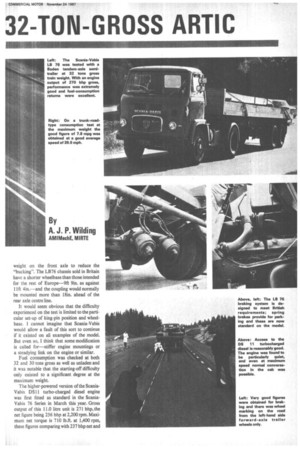

SINCE THE SCANIA-VABIS LB76 was road tested in the summer of 1966, a number of changes have been made to the model, including a more powerful engine. And after testing the latest version I am able to report: very good fuel consumption figures and brake stopping distances that have rarely been bettered by maximumgross artics in recent years.

The earlier road test was arranged by Scania-Vabis (Great Britain) Ltd. in conjunction with York Trailer Co. and took place in an area—around Corby— which did not have a consumption circuit comparable to those normally used by COMMERCIAL MOTOR. This could have affected the results in m.p.g.

And another reason for poor results could have been that the semi-trailer used was a three-axle design. Additional scrub on corners due to this layout (it was a twisting consumption route) could have resulted in extra fuel being used and the semi-trailer certainly played a part in the poor braking figures for its wheels locked on all the stops.

This time Scania-Vabis suggested that I go to Sweden to do the test. A Roden semitrailer was taken to the Sodertiilje factory to be coupled to a tractive unit which had been used for demonstration purposes in Britain, so the outfit tested was exactly as one that would be operated in this country.

Routes for fuel consumption tests were found which were, in my estimation, completely comparable to those normally used in Britain, therefore the figures obtained can be judged directly against results obtained on tests of other makes of chassis in the same class.

And as would be expected, an engine with an output of 256 bhp net pulling 32 tons gave acceleration times which were extremely good.

But against these figures the test showed up one unsatisfactory aspect of the design. On the original test, softness of the front suspension in conjunction with engine mountings which did not seem stiff enough caused difficulty in starting off on gradients. The same happened this time, not only for me but also for Swedish drivers, and probably because of the strain put on the transmission in repeated attempts at restarting in bottom gear up a 1 in 6.25 gradient, the propeller shaft broke (the splined shaft at the sliding end) before this could be accomplished.

When a replacement shaft had been fitted and a technique for starting on gradients of this severity was developed, satisfactory re

starts were made without too much trouble.

With the degree of effort made by ScaniaVabis to ensure reliability, it was surprising that the shaft had broken. But investigations showed that the component on the test vehicle while being one of the new stronger type introduced for the higher-power engine, was one of a number known to have been wrongly heat treated; at the beginning of production the material used for the splined end had been made too brittle in some cases. All suspect stocks were withdrawn and in those isolated instances where a failure occurred through a component slipping through the "net" the shafts have been replaced immediately. This was obviously another case of a vehicle left in the "demonstration stable" being overlooked.

On first taking over the Scania, however, I found it Was very easy to induce "bucking" of the front end when starting off even on the level. After driving the vehicle for half a day I rarely had trouble but still got into difficulties on occasions when I started off too casually.

There was scope to mount the fifth-wheel further forward on the tractive unit; at 32 tons the driving axle was a little over 10-ton UK limit. This may have put sufficient extra

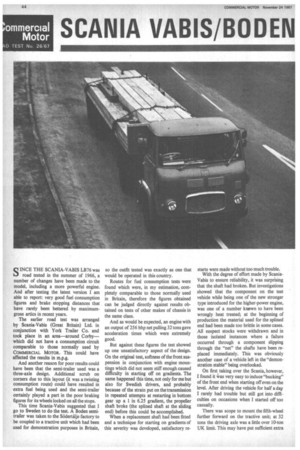

weight on the front axle to reduce the "bucking-. The LB76 chassis sold in Britain have a shorter wheelbase than those intended for the rest of Europe-9ft 9in. as against lift 4in. and the coupling would normally be mounted more than I8in. ahead of the rear axle centre line.

It would seem obvious that the difficulty experienced on the test is limited to the particular set-up of king-pin position and wheelbase. I cannot imagine that Scania-Vabis would allow a fault of this sort to continue if it existed on all examples of the model. But even so, I think that some modification is called for—stiffer engine mountings or a steadying link on the engine or similar.

Fuel consumption was checked at both 32 and 30 tons gross as well as unladen and it was notable that the starting-off difficulty only existed to a significant degree at the maximum weight.

The higher-powered version of the ScaniaVabis DS11 turbo-charged diesel engine was first fitted as standard in the ScaniaVabis 76 Series in March this year. Gross output of this 11.0 litre unit is 271 bhp, the net figure being 256 bhp at 2,200 rpm. Maximum net torque is 710 lb.ft. at 1,400 rpm, these figures comparing with 237 bhp net and 665 lb.ft. at the same speed respectively for the engine previously employed.

All Scania-Vabis vehicles delivered in Britain in 1967 have had the higher-output engine and introduced at the same time were an oil cooler, an alternator together with stronger transmission components.

Basically the transmission has stayed the same with a five-speed synchromesh main gearbox and two-speed epicyclic splitter section. And the brakes have not been altered, neither in the type of system used nor in the size of brake shoes. But the secondary system on all the Scania-Vabis 76 Series has now been standardized in line with equipment developed for the British market.

There are spring-brake actuators at both axles, the spring sections providing for both the secondary-system and parking brake functions. A hand valve in the cab exhausts air from the diaphragms holding off the springs and at the same time pressurizes the "auxiliary" connection for the semitrailer to provide the secondary system. This hand valve is also the parking brake control; lOsec after application, air is exhausted from the semi-trailer brakes leaving the brakes on the tractive unit only applied.

The semi-trailer used for the tests was a Roden Mark 3 tandem-axle model with a 32ft platform body. With the coupling mounted on the tractive unit at 181n. centres from the driving axle, and a load of 20.8 tons on the semi-trailer, the distribution of the 31 tons 7.75cwt gross weight was 5 tons 15.5cwt on the front axle, 10 tons 4cwt on the driving axle and the rest on the semitrailer bogie.

While the fifth-wheel coupling could have been mounted further forward to give less weight on the driving axle when operating at the 32 tons for which the LB76 is sold in Britain, the driving axle weight was within the 10-ton UK limit at 30 tons gross.

Tests were carried out at 32 tons even though the outfit would have been illegal in this country at present because it did not have sufficient outer-axle spread. As is well known, the 38ft spread required for 32 tons is virtually impossible for normal haulage because of our current maximum length limit of 42ft 7.75in. When the proposal to increase this figure to 15 metres (49ft 2.6in) is turned into law 32 tons will be entirely practicable on a four-axle artic.

First tests carried out were braking and acceleration and for these the Scania-Vabis test track near its factory in Sodertilje was used. Brake tests gave the excellent figures to be seen in the results panel. These represent overall efficiencies of 52 per cent from 20 mph and 57 per cent from 30 mph comparing with Tapley-meter readings of 66 and 68 per cent respectively for these speeds. This shows that there was not excessive delay in full application of the brakes and another commendable feature about the design was that there was minimum wheel locking. The only wheels that did lock were those on the lefthand side of the forward semi-trailer axle; they locked for most of the way on every stop.

Because there were no suitable hills on which to carry out hill-performance tests and brake-fade tests these were not done, but to simulate the latter the outfit was driven for 2 miles in 3rd/high with maximumthrottle applied and the brakes on to restrict the speed to 20 mph. After the tests all brake drums were extremely hot and smoking but even so there was not a great reduction in efficiency; a Tapley-meter reading of 50 per cent was obtained from 20 mph, a drop of only 16 per cent from the cold-drum figure. The test was at least as severe as fade checks carried out on tests in Britain so it would be safe to say that the Scania-Vabis will not suffer from fade problems. Nothing was lost by not being able to do a hill-climb test. The results of the acceleration runs were so good that the outfit would have romped up Bison or similar hills used in Britain. But it was still possible to do hill-starts as Scania-Vabis has a number of test slopes on its track. One of these has been made 1 in 6.25 because this figure appears in the British regulations. It was on this slope that the transmission trouble occurred. But before it, reverse restarts up the slope were completed satisfactorily. Reverse/low was necessary and it was almost possible to get away with the high ratio of the auxiliary section of the gearbox engaged but excessive clutch slip prevented this.

As already stated, after the propeller shaft had been replaced and a correct starting-off technique developed fairly easy restarts up the slope in 1st/low were made. Both facing up and facing down the slope the spring brakes on the tractive unit axles held the outfit without trouble.

To find acceleration times that are comparable with those obtained with the ScaniaVabis it is necessary to look at tests of 7and 8-tonners. The vehicle was extremely quick off the mark and reaching 40 mph in 43.7sec is quite remarkable for an outfit grossing 32 tons.

While at the test track maximum speeds in the gears were checked and found to be 5.5, 11, 19,32 and 46 with the low auxiliary ratio engaged and 7.5, 14, 25, 44 and 60 with the high. While there are 10 forward ratios it will be seen that top/low and fourth/ high are very close so that there are effectively only nine. This is of little relevance as I found no real call to split the ratios.

With so much power available there would have been no embarrassment on the type of routes I covered to have been without the two-speed section. On long hills such as are met with on intercontinental runs the picture could be different. The split ratios would allow the most suitable combination to be selected to get the best out of the engine and the extra-low bottom gear of 10.37 to 1 will be invaluable on the very steep gradients.

The gear speeds quoted are as recorded on a special Keinzle speedometer which had been corrected for accuracy prior to being fitted to the test vehicle. The figures represent the maxima with the outfit fully loaded. When empty there was an appreciable increase when in the higher gears due to a fairly long "run-out" on the governor. This was well over 10 per cent.

As will be seen from the results panel the average speed on the high-speed run when unladen was 66 mph. For this run, on a motorway between Sodertalje and Stockholm, a flying start was made and the fuel metering equipment fitted by Scania started and stopped at specific points.

Consumption checks were made at 32 tons and at 30 tons gross as well as unladen to give a complete picture of the consumption pattern. A most surprising thing about the results was the similarity between the 32and 30-ton figures. Only the former are shown in the table, the figures for 30 tons being 7.85 mpg at 38.0 mph average speed when cruising on the undulating route at up to 40 mph and 6.65 mpg at 54.3 mph average speed on the motorway.

Both routes used were similar to test routes employed in Britain. There were one or two gradients that would make a downward gear change necessary on a maximum-gross artic with the more usual power-to-weight ratio of 6 bhp per ton. But not the ScaniaVabis. The only changes needed were on the 40 mph runs on difficult bends. On the motorway, the tests were completed in top gear all the way with little drop from the maximum speed.

At no time on these particular tests or at any other while I was with the vehicle was there any feeling that the outfit was running at the maximum gross weight. The engine was quiet and hardly any noise entered the cab. All controls were found to be light and the steering was very easy yet with sufficient "feel". Braking was responsive and progressive so that there were none of the anxious moments that used to be common when driving some heavy chassis.

It was altogether a pleasant experience driving the Scania. There is every comfort for the driver in the well-fitted and roomy cab and the difficulty in starting off was the only really black spot. I said this could have been partially due to the soft front suspension and this point tended to be confirmed when there was some pitch and bounce at the front end on certain ridged road surfaces. Here again the shorter-thanusual wheelbase for the model could have played a part and it seems rather a shame to have to make this criticism of a vehicle that most drivers would feel to be near perfect.

Operators, too, would find advantages with the model. Good average speeds are possible at an acceptable consumption level —once again it was shown that high-powered engines do not necessarily give poor fuel returns—and the make has got a good reputation for reliability.

In Britain the LB76 32-ton tractive unit has a net-user price of £4,500.