N ORMALLY, after a hard day's test, I am not tired,

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

but at the end of the trial of the Electruk I was footsore and weary. The reason is that the vehicle is a pedestriancontrolled battery-electric model, and I was satisfying myself that the maker's claim of eight miles per charge under average conditions, using the smaller of alternative sizes of battery, was fully justified. As the tests proved, there is at least a

• 20-per-cent. safety factor in that • claim.

• Before testing the Electruk, I little realized how unlikely it would be for a retail-delivery salesman to run such a vehicle to a standstill. My test involved walking with the vehicle for 10 miles. If I had also been walking to and fro, between the van and the houses„ delivering milk or bread, I should probably have covered a further 10 miles.

Up to Six Miles a. Day

If the roundsman were to walk 20 miles during the day, he would have little time to spare for his customers. The distance covered by a pedestrian-controlled vehicle is, in practice, three to six miles.

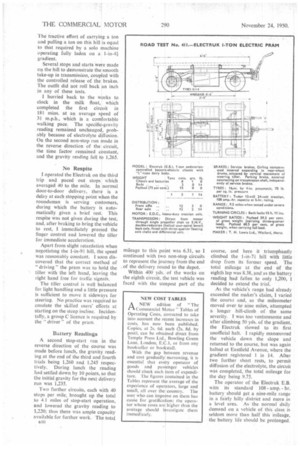

To make conditions worse than average, the course was planned over an undulating circuit, slightly more than a mile long, with gradients ranging from 1 in 40 to 1 in 9i. A start from rest on a 1-in-7i section was required every two miles. To simulate service conditions, dairy work being the most severe, a threequarter load was carried for the entire test. This is equal to leaving the depot with a full load and returning with a half-load made up of crates and empty bottles.

40 Halts Per Mile

In everyday service, the pedestrian-controlled vehicle has a nonstop run to the point of first delivery, This in my test was two laps of the circuit, equivalent to 2.22 miles, which is more than the average distance to the first• call on a pedestrian round. On average, milk is delivered at the rate of one to three stops per gallon; I specified 40 halts per mile during the delivery section, which corresponds to 2i stops per gallon.

Having established conditions which would test the range and hillclimbing capacity combined, I examined the chassis before starting off on the road. First, a pilot cell was selected for gravity readings. After releasing two catches at the front, the body was raised on its hinges to expose the whole chassis. This makes the task of 'maintenance

indeed simple. If required, the entire body can be removed by releasing two nuts at the hinges.

Apart from a separate hand-brake lever, which operates a contracting band on a transmission drum, all driving controls are grouped at the head of the tiller. For service use, Girling internal-expanding brakes are fitted to the rear wheels. They are automatically applied as the tiller is raised and are full on when the vehicle is not being driven.

Sideways movement of the tiller controls the Ackerman steering linkage to the front wheels, the axles and the chassis being replicas of those used in the larger conventional commercial vehicles. The front axle is attached to the frame through a central pivot to give full articulation.

The motor is centrally mounted in the frame and is linked by a shaft.

with flexible couplings, to the fullwidth double-reduction axle, which is complete with a differential unit. The driving axle is mounted in plummer blocks, in which it can partially rotate in opposition to two singleleaf reaction springs to absorb starting and braking stresses.

A finger switch in the tiller grip operates the controller gear, which is arranged for four-step automatic acceleration; all circuits are made or broken by a sliding contact on carbon brushes. The Tudor 24-volt batteries of 108-amp.-hr. capacity at the 5-hr. rating are carried pannier fashion on each side of the chassis between the wheels.

Good Balance The design of the Electruk is notable for balance, and the load is equally proportioned between the axles, whether the body is loaded or empty. A feature of the chassis is the use of a full-width track at the front and rear.

After adding the 15-cwt. payload, I checked the numerous fool-proof devices which protect the chassis and electrical components against mis use. First I pressed the starting switch with the tiller raised, but nothing happened. A micro-switch interrupts the circuit to the controller solenoid when the service brakes are on, and until partial depression of the tiller has commenced to release the brakes. The switch operating cam is set to close the switch before the brakes are completely released, thus enabling the motor to energize and prevent runback when starting on a gradient.

After inserting a dummy charging plug, the Electruk again refused to move, because of a switch which interrupts the controller circuit when the vehicle is connected to the charger. Then I left the parking brake applied, but again the circuit could not be completed.

Smooth Shunting

My next efforts were extended towards shunting, and here the smooth take-off afforded by the con trol system proved invaluable. It required no practice to inch the vehicle into position at theloading bank, but after setting the main switch to "forward," to move away from the bank, the pram refused to move. By not pushing the switch fully home, I had unknowingly found another safeguard in the Electruk. To prevent contacts from being burned by partially completed 'circuits, the main switch will not pass current until the contacts are fully engaged.

After setting a specially fitted mileometer to zero and synchronizing watches, the Electruk was led away by the first roundsman on the initial non-stop circuit. The battery electrolyte reading in the pilot cell was 1,280, and the temperature 53 degrees F. The compensation for the electrolyte temperature was insufficient to require adjustment of the reading.

Two Tons up 1 in 71

While this circuit was being run off, two more chassis were produced from the assembly bay, one of which was minus the propeller shaft and was being towed by the other pram. These two were fitted with platforms and loaded so that the complete chassis was carrying a ton, land pulling a ton, in the form of the second chassis and its load. The two were then led to a nearby hill of 1-in-8 average gradient and 200 yds. long.

Stopping at a point where the incline measured 1 in 71, the service and parking brakes of the towing vehicle were tested separately and held. both chassis. At the word " go," the driver of the leading vehicle pressed down the tiller, and the two units moved away from rest without the slightest trace of snatch. The tractive effort of carrying a ton and pulling a ton on this hill is equal to that required by a solo machine operating fully laden on a 1-in-41 gradient.

Several stops and starts were made on the hill to demonstrate the smooth take-up in transmission, coupled with the controlled release of the brakes. The outfit did not roll back an inch in any of these tests.

I hurried back to the works to clock in the milk float, which completed the first circuit in 181 mins, at an average speed of 31 m.p.h., which is a comfortable walking pace. The specific-gravity reading remained unchanged, probably because of electrolyte diffusion. On the second non-stop run made in the reverse direction of the circuit, the time factor remained constant, and the gravity reading fell to 1,265.

No Respite I operated the Electruk on the third trip and paced out stops which averaged 40 to the mile. In normal door-to-door delivery, there is a delay at each stopping point when the roundsman is serving customers, during which the battery is automatically given a brief rest. This respite was not given during the test, and, after braking to bring the vehicle to rest, 1 immediately pressed the finger control and lowered the tiller for immediate acceleration.

Apart from slight retardation when negotiating the 1-in-91 hill, the speed was reasonably constant. 1 soon discovered that the correct method of " driving " the pram was to hold the tiller with the left hand, leaving the right hand free for traffic sigrials.

The tiller control is well balanced for light handling and a little pressure is sufficient to move it sideways for steering. No practice was required to emulate the skilled users' efforts at starting on the steep incline. Incidentally, a group C licence is required by the " driver " of the pram.

Battery Readings A second stop-start run in the reverse direction of the course was made before lunch, the gravity reading at the end of the third and fourth trials being 1,260 and 1,245 respectively. During lunch the reading had settled down by 10 points, so that the initial gravity for the next delivery run was 1,235.

Two further circuits, each with 40 stops per mile, brought up the total to 4.1 miles of stop-start operation, and lowered the gravity reading to 1,220; thus there was ample capacity available for further work. The total Bin mileage to this point was 6.31. so I continued with two non-stop circuits to represent the journey from the end of the delivery round to the depot.

Within 400 yds. of the works on the eighth circuit, the test vehicle was faced with the steepest part of the

course, and here it triumphantly climbed the 1-inz7} hill with little drop from its former speed. The total mileage at the end of the eighth lap was 8.38, and as the battery reading had fallen to only 1,200, I decided to extend the trial.

As the vehicle's range had already exceeded the maker's claim, I varied the course and, as the mileometer moved over to nine miles, attempted a longer hill-climb of the same severity. I was too venturesome and after climbing 50 yds. of the gradient, the Electruk slowed to its first unofficial halt. I rapidly manceuvred the vehicle down the slope and returned to the course, but was again halted at Eastfield Avenue, where the gradient registered 1 in 14. After two further short rests, to permit diffusion of the electrolyte, the circuit was completed, the total mileage for the day being 9.75.

The operator of the Electruk E.B. witn its standard 108 amp. hr. battery should get a nine-mile range in a fairly hilly district and more in a level area. As the normal daily demand on a vehicle of this class is seldom more than half this mileage, the battery life should be prolonged.