What a waste 1

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Some 25 years after the gates were closed on the Scammell factory at Watford, CM looks back at this loss to the UK's truck manufacturing industry and the great waste of talent Words: Brian Strong / Images: Bob Tuck Talk to any accountant worth their salt and they'll tell you that closing the Scammell factory at Watford in 1988 was a case of good business sense. Their argument is bound to be supported by all the Daf marketing guys you can find. "Why," they would say, "keep a small, non-descript — and very old — factory going in the northern suburbs of London when you have masses of brand new production space readily available in the town of Leyland that can make the same vehicles but in a quicker, cheaper and more efficient fashion?"

You can imagine the rush by the Leyland management of old to ring the death knell for Scammell "Why didn't we think of doing this years ago?" would have been the question they asked as the cheque they received for the sale disappeared into the almost bottomless pit of Leyland's debts.

In fairness, that question had been asked many times, but before we come to the answer — which had also been given many times before — let's spare a minute to discuss what a mess the once highly respected Leyland Empire was in just 25 years ago.

Anyone with even the slightest appreciation of what a tremendous organisation Leyland was (in its pre-British Leyland days) would probably shed a few tears wondering why in the late 1960s it was signed up to take on the mess of the car Goliath Austin/Mon-is/British Motor Corporation. Once it did, its demise was inevitable and although saved in the mid-'70s by the British government, it became a political hot potato and the merger with (all right, takeover by) Daf was the only way out.

With Daf having no interest in what was going on behind the Scammell factory gates, for the sake of tidiness and expediency, it was a given that this offshoot of the old Leyland Empire would soon be demolished to make way for housing.

This closure was the first real blow to the UK's CV building industry. The following years would see Seddon Atkinson, Leyland, Foden and ERF become casualties.

But while the demise of Scammell was certainly a loss to all those on the factory payroll, was it a waste? And why hadn't the place been closed a lot earlier?

Sixty years of heritage Scammell might have been a mass producer, but where it really shone was by doing things other people hadn't really tackled.

Everyone knows about its achievements in the heavy haulage world. The Scammell engineer OD North came up with the plans to create the first vehicle to carry 100 tons of payload — single handed — which blew everyone's mind away in 1929. Only a couple of these were made but making more of an impact were products such as the frameless articulated tankers and the three-wheel mechanical horse/scarab.

Thinking outside the box was always part of the Scammell philosophy. "There was great scope for young engineers to be given a lot of responsibility," says John Fadelle, who became a heavy and military vehicle engineer during the 20 years he spent with Scammell "If you showed an interest in something, you normally ended up doing it."

In the late '60s, Fadelle reckons there were about 1,000 on the payroll but, just before the closure, staffing dropped to around 700. "Manufacturing techniques improved," he says, "but the main reason the numbers fell was because we stopped making things like cabs and gearboxes in-house."

Fadelle recalls getting a huge amount of job satisfaction at Scammell: "We were totally different to the mass producers of AEC, Guy and even Leyland, as we did all the exotic specials so a lot of people on the shop floor were quite fulfilled. And with Vic Wilkes at the helm, we had a great leader."

Scammell was taken over by the Leyland Group in 1955, but retained its own identity until the moment the gates were closed in July 1988. The reason Leyland left it alone was simply because Scammell made money. "We had so many different projects to think about," says Fadelle, "and the brief was that as long as the firm made a profit, then you could get on with it."

So, again, why close a profitable operation?

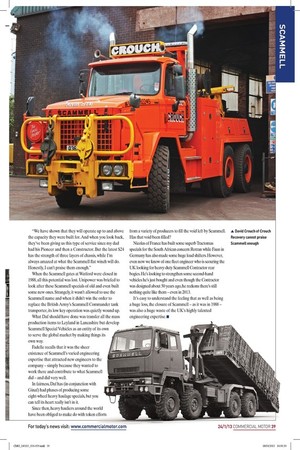

True grit Scammell (of old) never won many plaudits from the guys behind the wheel of its hardware because, generally, the vehicles were hard, unforgiving and uncomfortable to drive. However, when it comes to operators there is praise aplenty from people such as David Crouch, who can look back on 50 years witnessing all manner of Herculean feats carried out by an assortment of Scammells.

The Leicestershire concern of Crouch Recovery now runs a fleet of 34 but when the chips are down or conditions extreme, they still rely on their 'ancient' Scammells to do things lesser, modern hardware wouldn't look at. "They might look old fashioned now," says Crouch, "but when the s**t hits the fan, and the job wants muscle and strength, and you are going to bend normal vehicles winching the almost impossible, then Scammell comes through time and again.

"We have shown that they will operate up to and above the capacity they were built for. And when you look back, they've been giving us this type of service since my dad had his Pioneer and then a Constructor. But the latest S24 has the strength of three layers of chassis, while I'm always amazed at what the Scammell flat winch will do. Honestly, I can't praise them enough."

When the Scammell gates at Watford were closed in 1988, all this potential was lost. Unipower was briefed to look after these Scammell specials of old and even built some new ones. Strangely, it wasn't allowed to use the Scammell name and when it didn't win the order to replace the British Army's Scammell Commander tank transporter, its low key operation was quietly wound up.

What Daf should have done was transfer all the mass production items to Leyland in Lancashire but develop Scammell Special Vehicles as an entity of its own to serve the global market by making things its own way.

Fadelle recalls that it was the sheer existence of Scammell's varied engineering expertise that attracted new engineers to the company — simply because they wanted to work there and contribute to what Scammell did — and did very well.

In fairness, Daf has (in conjunction with Ginaf) had phases of producing some eight-wheel heavy haulage specials, but you can tell its heart really isn't in it.

Since then, heavy hauliers around the world have been obliged to make do with token efforts from a variety of producers to fill the void left by Scammell Has that void been filled?

Nicolas of France has built some superb Tractomas specials for the South African concern Rotran while Faun in Germany has also made some huge load shifters. However, even now we know of one fleet engineer who is scouring the UK looking for heavy-duty Scammell Contractor rear bogies. He's looking to strengthen some second-hand vehicles he's just bought and even though the Contractor was designed about 50 years ago, he reckons there's still nothing quite like them — even in 2013.

It's easy to understand the feeling that as well as being a huge loss, the closure of Scammell — as it was in 1988 — was also a huge waste of the UK's highly talented engineering expertise. •