THE TON-MILE AS A UNT FOR STABILIZED RATES

Page 22

Page 23

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN my reference, in last week's article, to the suggested scheme for stabilized rates for road haulage, 1. raised strong objection to the use of the ton-mile as a unit for the assessment of charges. It may be recalled that in this scheme, put forward by a Yorkshire operator of standing and experience, it was suggested that, for long-distance traffic, there should be agreed a rate per ton-mile which, subject' to other conditions, should apply to all traffics.

Amongst the conditions was one with which, in principle, I did agree. It was implied, although not actually stated, that any classification should, far preference, have regard to vehicle capacity rather than the goods being carried. I do think that classification of vehicles is advisable.

'Now, one point which I would like to make is that these two conditions conflict. A flat rate per ton-mile is inconsistent, unless applied throughout the whole range of vehicles. If, therefore, vehicles be classified, the ton-mile basis of rates assessment becomes impracticable.

• It is true that the author of the scheme, whom I called Mr. A., suggested classification of vehicles only in respect of kind. He thought that some differentiation should be made as between vans, platform wagons, tipping lorries and special types ; he did not seem to suggest classification in respect of load capacity.

In my view, the classification should take size into consideration as well as type. In that case a flat rate per ton-mile will not be applicable and I hope to show, by some simple applications of the use of a flat rate per tonmile, that my view is correct.

In the proposed scheme a rate of 2d. per ton-mile was suggested, although admittedly this was only a tentative rate. Put forward as a basis for discussion and not by any means in any arbitrary manner, It will, however, serve as well as any other figure to illustrate my point.

Now, take as comparative examples the case where regular traffic is to be carried between Leeds and London— I shall take the distance, between the two places as a

round 200 miles—and assume that two competing hauliers are carrying similar trafficfor the same customer. One of them uses the lowest category of vehicle which Mr. A. thought should be included. in this scheme, namely, the inexpensive 30 m.p.h. 5-ton type. The other is using a maximum-load eight-wheeled. oil-engined vehicle, and is carrying 15 tons. Both of them charge, according to this schedule, at the rate of 2d. per ton-mile.

One of the principles laid down by Mr. A. was that the rates for all -traffics should be, as in the case of railway rates, based on one-way only. Abiding by that principle, then, in the course of a journey, the small vehicle will complete 1,000 ton-miles, that is 5 tons multiplied by 200 miles, and the large vehicle 3,000 ton-miles. At 2d. per. ton-mile the charge of the former will be £8 17s. 6d. and of the latter, £25. The rate per ton to the merchant is £1 15s. 6d., se that, at first sight, it would seem that everything is as it should be and that the merchant has no ground for complaint.

Detailsof Operating Costs for the Types of Vehicle Assume, also, so as to keep out problem as simple as pos:diale, that each vehicle is able to complete two round journeys per week so that the weekly mileage of each is 800. The operating cost of the smaller vehicle, according to The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs, is £23 10s. per week. The operating cost of the large vehicle, assum

ing that a second-man be employed, is £43 4s. per week.

Now, if it he reckoned that return loads are available to the extent of 50 per cent., that is to say, assume that the small vehicle in a week takes 10 tons from Leeds to London and brings back 5 tons, and, siirrilarly, the large vehicle takes out 30 tons per week and brings back 15 tons, then the respective revenues will be as follow :—for the small vehicle, £26 12s. 6d. per week ; tor the large vehicle, £75 per week. • The gross margin, the difference between revenue and operating cost, will be £3 2s, 6d. per week in the former case and £31, 16s. per week in the latter case. From these gross margins establishment costs must be subtracted. In the case of the small vehicle they are likely to be £3 per week, so that there the margin of net profit per week is • only 2s. ed. In the case of the large vehicle the overheads may be £9 per week, but that still leaves a margin of £22 les'. per week as net profit.

When the Disparity Persists in Profit-earning Capacity

, Even if I take full loads as being available in both directions, and there will be few who will expect that such will be the case, week in and week out, year by year, the disparity between the profit-earning capacity of these two • vehicles still remains. Indeed, it is exaggerated. In those circumstances, the small vehicle will earn a. total of £35 10s, per week, leaving a gross' margin of £12 • and a net profit of £9 per week. The large vehic„le will earn a total of 4100 per week, leaving a gross margin of £56 16s. and a net profit of £47 16s, per week, If I take pre-war costs the only difference is that the case of the small vehicle becomes practicable with 50 per cent. return loads ; the disparity in net profit between the two still remains.

The pre-war operating cost of a 5-tonner was £18 14s the basis of 50 per cent, return loads and earning, therefore, £26 12s. ed. per week, the gross margin is £7 18s. ed., and if establishment costs be taken as being

£2 10s., a net profit totalling es Sc. 6d. per week remains. If I take it that full loads are carried in both directions, then the revenue becomes £35 10s per week, the gross margin £16 16s. and the net profit £14 Os. per week.

In the case of the 15-tonnei, operating costs, including wages for a second-man would, in pre-war times, have been £35 8s. per week. With 50 per cent, return loads and a revenue, as shown above, of £75 per week, them is left a gross margin of £39 12s. and if establishment costs be taken then to have been £7 10s. the net profit would come out at £32 2s. per week. With 100 per cent, return loads the gross margin would have been £64 12s, and the net • profit £57 25. per week.

It should be noted that it is not the amount suggested to be paid per ton-mile that is wrong. It is not the 2d., it is the principle, the attempt to apply a flat rate per ton-mile to all vehicles, irrespective of load capacity. If, however, return loads be available only to the extent of 50 per cent, of the outward loads, then this figure of 2d. must be increased, accordingly, to 2.7d. That is the .rate which would have to be fixed for a 5-tonner operating .under the conditions named earlier in this article, and reckoning, on an average, one full return load for every

two outward loads. .

In the 'case of the 15-tonner, the vehicle operating cost, inekucling provision fos a second-man, will ;be £43 4s. and establishment costs £9 pe: week, making a total expendi

ture of £52 4s. per week. Add 20 per cent. for profit, £10 9s., and the minimum revenue is seen to be £62 13s.,, that is 18.8d. per mile run. If full loads be carried, the tonmileage is 15 and the rate must be lid. per ton-mile. If only 50 per cent. return loads be expected, then the rate Must be 1.67d., say, 1.1-d., per ton-mile.

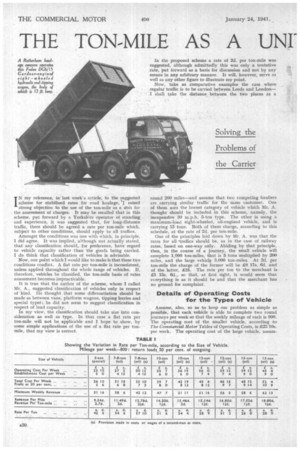

The figures in the accompanying Table I carry the argumenta stage farther. They show what the rate per ton-mile must be for different sizes of vehicle ranging from 5 to 15 tons.

According to the figures in the last line of Table I. the tonnage rate may vary by as much as 50 per cent, as between the smallest and the largest vehicles. S.T.R.