WHAT'S IN A ME?

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN Yorkshire tanker haulier Liquids, Powders & Gas is boosting its core business by offering training, tank cleaning and repair facilities to its competitors, in similar fashion to some of its larger rivals.

The Batley-based firm, which runs a fleet of 185 tankers, is expanding its hazardous goods training programmes and its tanker conversion and maintenance division, Retank, which it set up three years ago. The Calor subsidiary claims to be one of only two tanker operators running Government-approved hazfreight and hazpak courses for outside drivers. It says too that 60% of Retank's business is now with other companies.

LP&G should not be confused with LPG, the initials of liquefied petroleum gas, explains sales and marketing director Tony Gilroy. It used to use LPG on its livery, but this had unfortunate results when one of its trucks was in an accident about five years ago.

"When the firemen saw LPG they panicked. In fact, it was carrying a harmless product," says Gilroy, who insists LP&G must have a recognisable name and image if it is to establish itself as a big player in the industry.

Despite its name, the company carries no gases. Up to 75% of its loads are hazardous chemicals, mostly liquids, and 20% oils such as bitumen. Edibles, like beer and starch, form a small but growing part of its business. It carried no foods three years ago.

LP&G was bought by Calor in 1981 during a spate of transport acquisitions by the gas giant. Before that, it was privatelyowned. Founder Harold Wood sold his first tanker firm to NFC before starting LP&G from scratch in 1965.

Calor's other tanker subsidiary, Calor Transport, competes with LP&G only in oils. "Most of its business is gas. We are mostly chemicals, and Calor takes the view that we operate in separate markets," says Gilroy.

The company, which has depots at Teesside and at the premises of two of its customers in Rotherham and West Thurrock, is standardising its fleet to ERF, and has bought its first models this year. Until now, it has run mainly Dafs and Volvos, with some Seddon Atkinsons and Scanias.

The ERFs are more durable, says Gilroy. They have larger Cummins 325 engines and GRP cabs which do not corrode easily. Vehicles are currently being kept for five years, although the average age of the fleet is three.

The company is battling hard to win the BS5750 stamp of approval this year. As part of its preparations, LP&G has produced a quality manual for all its staff.

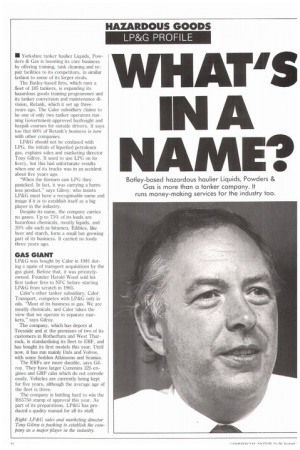

Right: LP&G sales and marketing director Tony Gilroy is pushing to establish the company as a major player in the industly. With many customers, such as ICI, inisting that their carriers must have, or be vorking to attain BS5750, he says achievng the mark as soon as possible is vital. lathers which fail such standards will find t hard to work for big companies.

LP&G's biggest customers are Croda in totherham, with 25 vehicles, and ICI. It ilso has contracts with BP Chemicals, ;hell, Exxon, Unilever and Procter & ;amble. Most last between three and five rears. The company also has about 50 pot hire vehicles.

The latest contract, begun in January, is vith Resinous Chemicals in Dunstan, Tyneside. LP&G supplies one dedicated anker and two on "afreightment", where hey are hired on a spot basis, but are :ommitted to working on the business. .,P&G uses a double shift to keep the actory supplied.

Afreightment is the worst arrangement or a busy haulier says Gilroy. Spot hire an be accepted or refused depending on vhether or not a vehicle is available, but vith this method, empty vehicles someimes have to be moved to keep the erms of the contract.

Jp to 85% of LP&G's dedicated fleet is in ts own livery, although some customers vant their own colours on a contract vehiIe. This can vary, however; often the ender of dangerous chemicals will not rant its name emblazoned on a tanker.

LP&G says its hazardous goods training rogrammes, headed by training and safey manager Alan Walker, are approved by he Chemicals Industries Association, and the other major chemicals and road ran span. organisations.

Most of the company's major rivals, inhiding Tankfreight, Boyer and Sadler, use .P&G's courses. Only United Transport uns its own programme, says Walker.

The training centre is self-financing.

own drivers are put through a refresher course every three years after passing their hazpak and hazfreight training. Managers also attend a special course. New laws making the training of supervisors compulsory come into effect in 1992.

Retank, the tanker conversion and repair division, is run from a separate building and has its own cost centre. Fleet engineer Eddie Mania, who heads it, says giving it a different identity allows competitors to use the facilities.

When we started, almost all our business was in-house. Now, it's 60% outside work in a good month," he says. The building includes 12 maintenance bays as well as a paintshop. Customers include BRS, Yorkshire Water, Total and Samas.

Up to 70% of trucks using its tank cleaning station at Batley belong to other firms. LP&G is also moving into container storage — mostly of chlorinated solvents — and has set up four tanks in its yard.

The company, which employs 213 drivers, 35 engineering and 35 office staff, buys most of its general-purpose tanks from manufacturers such as LAG in Belgium, Magyar in France and Hobur in Germany. It buys its specials from Crane Fruehauf or Clayton in Burscough.

Most of LP&G's customers are at the chemicals plants on Tyneside, Merseyside and Humberside, and Gilroy says West Yorkshire is a perfect central base from which to reach each of these areas. LI by Murdo Morrison.