AGRIMOTOR NOTES.

Page 25

Page 26

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Ploughing Speeds of the Agrimotor-3 ra.p.h. the Highest Economical Speed.

FROM TIME TO TIME one hears a good deal of discussion, especaally among farmers, as to the best speed for a tractor. The question is a very important one, and is not disposed of as easily as some farmers seem to. think. It is not merely a question of getting over the work which is involved, but also the necessity for accomplishment of firt.t

class work at an economical cost. .

In this .connection there are, many considerations to be taken into account. First we must consider the variety of soil reaistences, widths, depths. of cutting, and forma or shapes of ploughs, and when all this ia taken into• account, one is forced to the conclusion that the faster agrimotors are not the most economical. .Speed has to be compared, not with that of a horse, but with the number of furrows which are drawn by the agrimotor. , The case is put very well by Oliver B. Zimmerinan in Automotive Industries. As an example, he takes two well-designed outfits developed to travel at two and four miles per hour and to draw four and two bottoms respectively. Assuming for the moment that the drawbar horse-powers are equal and acreages ploughed in the mine. time are equal, with an eye to the power delivered at the drawbar, the following conclusions are drawn : (a The tractor must move itself and the plough over the ground twice as far in one case as in the other.

(b) The.number of turns at the end is twice as great in one ease.

(c) The strains due to striking hidden obstructions are greater at the higher speed.

These are the factors whieh, in the main, require more horse-power ahead of the drawbar at the higher speeds, as well as proper: care in -tesign.

Next is considered what happens to the rear of the drawbar. Here it is assumed, in order to cover a reasonable variety of soil resistance and number of ploughs, that there is a drawbar horse-power of 15 available. It is, therefore, assumed that for each , speed -of one mile per hour, up to five or six, the engine and tractor are properly designed for the speed considered, and of equal fuel economy per horsepower, above and below each mile of speed, -so that the merging shall be complete and uniform hem one into the other and the comparison as fair as possible.

Resort is had to the recently-published draught data of Professor Davidson, of Ames. Iowa, and that of the Kansas State Agricultural College. These are taken as the basio data, as the tests are in complete agreement with experimental data, developed by experienced commercial organizations in the past, and used by them in present-day designs. The data i

mentioned, n general, indicate that in each kind of soil, whether heavy or light, with the increase of speed there is a corresponding, increase of draught, the amount depending upon the sneed, shape of prough, and-the nature of the soil. In these tests it is shown that, with the stubble bottom, in light -soil an increase of 1.3 miles above 2.2 miles carries a draught increase of 240 lb., or, in other words, 59 per cent. increased speed causes a 75 per cent, increase in draught. With the combination bottom a 59 per oent. increase in speed causes a.66 per cent, increase in draught. With the breaker bottom a 63 per cent. increase in speed causes a 33 per cent. increase in draught.

The deduction is that with -an increase in speed there is a proportional increase in draught ;also that the leer, abrupt mouldboard has the least resistance. In Prof. Davidson's data is shown an increase in

speed from two to four miles, or 100 per cent., causing a draught increase of 33 per cent., and it is found that by increasing the speed by 100 per cent., that is, from two to four miles per hour, requires an increase in horse-power of 267 per cent. from 4.48 per plough to 11.95. Without going into any more details,at this stage, and leavingthe figures and diagratns-of the American experiments, we can form the opinien'that, for land work, very little is gained by any very great increase in speed. The main consideration the farmer should bear in mind, in deciding on a tractor, is its ability to perform the operations required of it in actual land work, We fear that many farmers desire speed in their tractors, in order that the appliances may be more rapid on the road and when used for other hauling purposes.. I have no hesitation myself. in saying that, except in particular cases, the tractor should not be used on the read. It is made for land work, and, of course, most reputed makes will perform almost every operation that requires power, and give satisfaction. The tractor will haul mowers and binders and also the loads of hay,and corn from the fields to ricks; it will also perform road haulage operations without injury, providing it is not made to travel too fast.

From the above reference to the Amecjean experi ments, ents, it will be quite clear tha increase ncrease of speed requiring an increase of horsepower will involve increased cost, and it may be useful to make a reference to the summary made by Mr. Zimmerman. Some of the conclusions drawn from the experiments are as follow:— 1: That the most economical ploughing speeds are unquestionably below three miles per hour, the cost rising rapidly from around two mites per hours 2. If the ploughs in the experiments had been designed specially. for higher ispeecls, the best that could be expected would be a less pronounced increase in costs, and in no case could the speed of maximum economy be raised to over three miles per hour.

3. It is evident that the better breaking up of the soil, at the higher speeds, is heavily paid for, and that it is more economical to perform the operation of harrowing, either separately or behind the plough, rather than to accomplish it by rapid ploughing. (This method of breaking up plough land is peculiar to the continent of America, and is not practised in this country except on the lightest soils.) 4. To obtain -the very best results, s.peecl ratios shouldoover the ranges from 11 to 3 miles per hour. This would permit of, meeting the various soil resistances. 5, It would appear that in heavy land and ploughing up to 8 ins. deep with small tractors, a greater acreage would be obtained by the use of 10 in. or 12 in. bottoms than of 14 in. bottoms., (These are the dimensions of furrow used in America.)

The Fordson Adapted for Stetch Ploughing.

The Fordson tractor has been adapted for stetch ploughing by Mr. S. C. Darby, engineer, of Wicldord, Essex. Mr. Darby's father, the late Mr. T. C. Darby, was a pioneer of the motor ploughing industry, and it is not surprising that, acquainted as he is. with the Essex ploughing methods, the son should apply his inventive inclinations to adapting the agrimotor for doing work hitherto done mechanically by steam tackle.

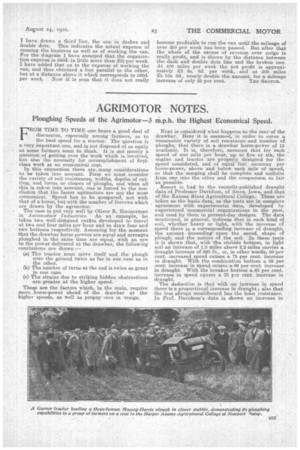

The adaptation is quite a novel one. The Fordson tractor has,been altered effectively to work stetch land. It will plough, and finish every stetch, and though the wheels always run where the stetch furrows are to be, they never knead the land portion of the steteh. It will satisfactorily pull a Smith drill and cultivator, or disc harrow, with all the wheels running in the stetch furrows, where they get the best possible grip and do the least injury to the next crop. The mode of adaptation can be seen in the illustration which accompanies this reference. Reconversion is capable of being quickly effected. Mr. Darby has, also invented a governor for Ford.son tractor engines, whicb. is controlled by the air pressure from the radiator fan. It is a very simple

and effective device. "A GRIXIOT.