REPLACEMENT RENOVATION?

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THERE, CAN BE few users of motor vehicles to-day who do not view with alarm the enormouS increase in the cost of repairs and the very serious effect which it is having on -the economics of road transportation. The heavy labour charges which the modern repair shop is called upon to bear is not the only factor contributing to the increased expense of keeping vehicles in goodeondition on the road; the inflated prices of spare parts, and the difficulty and delay which are often experienced in obtaining delivery of them have much to do with it.

• In a sense, the civil repair shop to-day is labouring

• under very •much the same difficulties as were the Army repair shops in .the later stages of the war. Then there was a period when the difficulty of getting spare pasts was so great and the wastage and scrap in transport vehicles was so enormous, that the upkeep of the Army transport system in the field was a matter of the utmost difficulty and the cause of grave concern to • those responsible for its efficient. maintenance.

Electro-deposition Saved the Situation.

It was during that period that the Army authorities, in their efforts to reduce the enormous amount of wastage that was taking place, turned to the process of electro-deposition as a means of salving a large proportion of the "scrap" and of cutting down their requisitionsfor supplies of new parts, whichwere straining severely the overtaxed resources of the factories at home. There is no question but that this process, which was developed during the war from the stage a experiment to that of practical utility, saved the country a vast amount of money, and enabled a very difficult period in the upkeep of the Army transport to be tided over.

So far as is known, it was in the • Army workshops that the first really successful application of the • principle of building up large quantities of worn-out parts by depositing new metal on them by electrical means was made. It was the application of an old-established principle to a new branch of work. A little light was thrown upon the uses to which the process of electro-deposition was applied, in salving parts which otherwise would have been scrapped, in a paper read a few months ago before the Institution of Auttenombile Engineers by Major B. H. Thomas, who had much to do with putting it on a practical and successful footing at one of the heavy repair shops in France. The paper dealt with the scientific aspects of the subject, but• the story of how success Was attained, after innumerable difficulties had been surmounted under most adverse conditions, might well be called a romance of renovation.

'Early attempts were not very successful. Following upon thv well-known lines of electro-plating, it was usual to deposit on the worn surfaces first of all a layer of capper—a comparatively simple process—then on top of that a coat of bard iron. The chief difficulty was e8 to get the layer of deposited metal to stick. Copper was found to be necessary in the early days in order to secure a reasonably firm adhesion of the iron, but it was really only a makeshift method, as the deposit so formed was not satisfactory when applied to parts subjected to wear, and was, of course, unable to withstand heat treatment. This is easily understood, as copper is a soft metal, and it cannot be expected that a wearing part should stand up indefinitely, with a layer of copper beneath an outer skin which could not be case-hardened.

Correct Method Difficult to Achieve.

The direct deposition of metal was obviously the ideal at which to aim, but it was one exceptionally difficult to achieve. While to secure adhesion was the chief trouble, and to ensure that the deposited layer of metal would not strip under wearing conditions, other problems equally baffling cropped up. Sometimes the deposit was porous, at others brittle—

incomprehensible variations in the quality of work turned out, under conditions which were practicallyidentical, had to be analysed and an explanation sought. It was only after a great deal of experiment and research work had been carried out that the process finally approached success.

Many data were gatheeed and collated during the war period by Major Thomas and others,. but even at the conclusion 'of hostilities the process could hardly have been claimed to be a commercially useful proposition.

Revolutionizing Repair Work.

Since then, _however, undor more peaceful conditions, which iiave permitted closer investigation, Major Thomas has continued his experiments, directing hisefforts entirely towards the placing of the laboratory process on a footing which would make...it a pra-ctical commercial proposition, the utility of which would he unquestionable, and which would bid

fair to effect a revolution in the modern repair shop methods. In conjunction with Lieut.-Col. Kennedy, who, as commanding officer of one of the largest-M.T. heavy repair shops in the war, had been able to appreciate to the full the possibilities of this work, a laboratory was established and equipped with al the incidental appliances 'necessary to the eiectiodeposition of metal for the purpose of renovating warn-out parts. They were encouraged in this pioneer work by the knowledge that the scope for the process, if it could be properly carried out, would be enormous. It need S little imagination to see that such would be the case. When it is considered that every day, in practically every. repair shop in the country, expensive parts, costing, it may be, anything from k.:5 to £50, are being scrapped simply because the outer surface of the metal has WOrrl away, although the wear may be almost infinitesimal--a few thousandths of an inch—it will be appreciated that the 'economies to be effected are such as to ensure a tremendous demand for renovation. work. Simply because, nntil very recealy, science had devis4 no means, of replacing metal which_ had worn away, this scrap had come to be looked upon as inevitable. If eleetro-deposition be a practical process, it need he inevitable no longer.

Cutting Down Costs.

It is, we understand, the aim of 'the EleetroFerrous-Engineering Co., Ltd., in which Col. Kennedy and Major Thomas are now concerned, to make such wastage unnecessary in the future. No claim is made by Major Thomas or his associates to have originated the process. Their claim —and it is one which appears to be amply justified—is that they have put it on a commercial footing, co that they are in a position to render the utmost assistance to those responsible for the repair and main tenance of motor vehicles—or, ; deed, almost any class of machinery —to effect economies which are of the most vital importance at the present time. The scrap-heaps of some repair shops are astonishing. Often they consist largely of costly parts which are considered useless simply because a few thousandths of an inch of material are worn off them often over a -small area, " Yes,"Aays the critic, " that may be so, but then neW parts are comparatively easy to obtain, and they don't cast very much." Now, with present-day conditions what they are, that argument does not seem to be a sound one. Spare parts are often by no means 'easy to obtain, and their cost is, as has .been mentioned before no inconsiderable factor in the heavy repair, and maintenance charges which have to be met at the present time So far as we can gather, what the sponsors of this new industrial process say in effect is this : "We will take your scrap heap—or most of it—and we will return the parts to you in such a condition that youcan put them into your finished stores, or, if you like, straight into a vehicle ; that is to say, we will return the parts to you in such a condition that they' are equal to and indistinguishable from new parts, and we will do it for approximately half the cost that you would have to pay for new parts, and With leas delay than you would, in many cases, experience in getting them." That, undoubtedly, is an attractive and a practical proposition. If it can be carried out, it means literally the abolition of the scrap heap, that bugbear of an engineering shop to which most people have become so accustothed as to condone, Times are too hard to-day for a mounting scrap pile to be regarded with complacence, and it can be said, Without exaggeration, that if this process of electro-deposition has been made a practical. proposition, a new era in repair shop practice will have dawned, equally as significant as the coming of autogenous welding, and which promises to cover an oven wider ft6ld of utility.

A Pioneer Plant.

We recently had the opportunity of inspecting the laboratory and workshops in which this work is being done. Though we are not Art liberty to _publish vary detailed particulars of the process, we were given ample opportunity of inspecting it and of satisfying ourselves as to its undoubted success in the applica

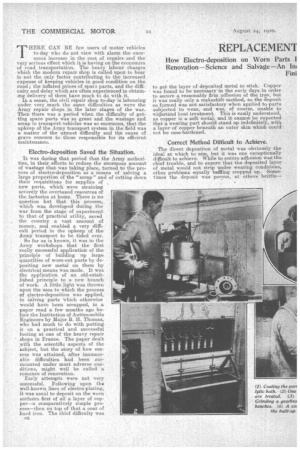

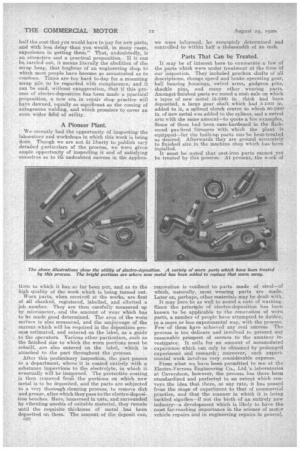

tions to which it has so far been put, and as to the high quality of the work which is being turned out.

Worn parts, when receives at the works, are first of all checked, registered, labelled, and allotted a jab number. They are • then carefully measured up by micrometer, and the amount or wear which has to-be made good determined. The area of the worn surface is also measured, and the ampereage of the current which will be required in the deposition process estimated, and entered on the label, as a guide to the operators. Various other particulars, such as the finished size to which the worn portions must be rebuilt, are also entered on the label, which is attached to the part throughout the process.

After this preliminary inspection, the part passes to a department, where it is coated entirely with a substance impervious to the electrolyte, in which it eventually will be immersed. The protective, coating is then removed from the portions on which new metal is to be deposited, and the parts are subjected to a very thorough cleaning process, to remove dirt and. grease, after which theyt pass to the electro-deposition benches. Here, immersed in vats, and surrounded by vibrating anodes of suitable material, they remain until the requisite thickness of metal has been deposited on them. The amount of the deposit can, 010 we were informed, be accurately determined and controlled to within half a thdusandth of an inch.

Parts That Can be Treated.

It may be of interest here to enumerate a few of the parts which were under treatment at the time of our inspection. They included gearbox shafts of all descriptions, change speed and brake operating gear, ball bearing housings, swivel arms, gudgeon pins, shackle pins, and Many other wearing parts. Amongst finished parts we noted a stub axle on which a layer of new metal le-1000 in. thick had been deposited, a large gear shaft which had 5-1000 in. added to it, a splincd clutch centre to which 90-1000 in, of new metal was added to the splines, and a swivel arm with the same amount—to quote a few examples. Some of them had been ease-hardened in the Richmond gas-fired furnaces with which the plant is equipped—ter the built-up parts cam be. heat-treated as desired. Afterwards they are ground accurately to finished size in the machine shop which has been installed.

It must be noted that cast-iron parts cannot yet be treated by this process. At present, the work of renovation is confined to parts made of steel—of which, naturally, most wearing parts are made. Later on, perhaps, other materials may be dealt with. It may here be as well to sound a note of warning. Since the principle of electro-deposition has been known to be applicable to the renovation of worn parts, a number of people have attempted to dabble, in. a more or less experimental way, with the process. Few of them have achieved any real success. The process is too delicate and involved to present any reasonable prospect of success to the amateur investigator. It calls for an amount of accumulated experience which can only he obtained by prolonged experiment and research ; moreover, such experimental work involves very considerable expense.

From what we_ have been permitted to see at the Electro-Ferrous Engineering co., Ltd.'e, laboratories at Caversham, however, the process has there been standardized and perfected to an extent which conveys the idea that there, at any rate, it has passed frera the stage of experiment to that of commercial practice, and that the manner in which it is being tackled signifies-4f not the birth of an entirely new industry—a development which is likely to have the most far-reaching importance in the science of motor vehicle repairs and in engineering repairs in general.