EFFICIENCY AND WHERE THE PETROL GOES.

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Many Operators are Conscious of Excessive Fuel Consumption for their Fleets of Vehicles. Hints as to Possible Causes of this Defect with Suggestions for Remedies are Given in this Article.

DETROL consumption is a much-debated topic. Many

vehicles are seemingly inordinately economical in the consumption of the precious spirit, whilst others are very wasteful. Why is this? Is it due to driving methods, variation in loading, adjustment of engine details, engine design, .earhuretter setting, or what? The answer is not far to seek; indeed, it is quite easy to make a comprehensive reply, for every feature mentioned above has a distinct bearing upon the rate at which fuel is consumed.

The owner or operator who pays minute attention to detaitis the man who gets the best results from the petrol consumed by his fleet. It is only by keeping a watchful eye upon the behaviour of any particular vehicle that it can be maintained in thoroughly sound order and its efficiency be kept at a high level. • It is the considered opinion of the writer that all vehicles, whether they form part of a fleet or whether they are individual ones operated by an ownerdriver, should be continually checked for fuel consumption. Indeed, it is preferable to record each run, noting in a log the distance travelled, the type of load and the amount of petrol consumed. The work entailed is not very great, and the results secured from the knowledge thus obtained will unquestionably repay the effort expended.

So much for what might be termed the ethics of the case. The manner in which the fuel, mileage and journeys are all logged can be left to.the operator, as each individual ease will require different treatment.

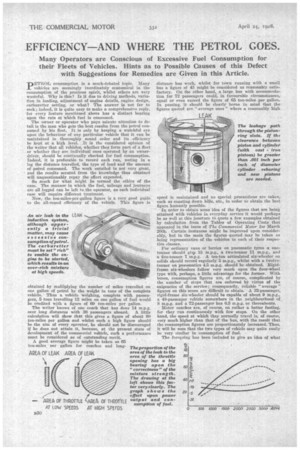

Now, the ton-miles-per-gallon figure is a very good guide to the all-round efficiency of the vehicle. This figure is obtained by multiplying the number of miles travelled on one gallon of petrol by the weight in tons of the complete vehicle. Thus a vehicle weighing, complete with passengers, 5 tons travelling 12 miles on one gallon of fuel would be credited with a figure of 60 ton-miles per gallon.

The writer knows of one coach that has done 14 m.p.g. over long distances with 30 passengers aboard. A little calculation will show that this gives a figure of about 80 ton-miles per gallon and whilst such a high figure should be the aim of every operator, he should not be discouraged if he does not attain it, because, at the present state of development of the commercial vehicle, such a performance must be considered as of outstanding merit.

A good average figure might be taken as G5 ton-miles, ver gallon for coaches and long

— /AREA OF THROTTLE it'APEA OF THROTYLE AT LOW SPEEDS a HIGH SPEFDS

)330

distance bus work, whilst for town running with a small bus a figure of 45 might be considered as reasonably satis-. factory. Olt. the other hand, a large bus with accommoda-. tion for 72 passengers could, in favourable circumstances,equal or even exceed the figure of 65 ton-miles per gallon.. In passing, it should be clearly borne in mind that the, figures quoted are "average ones" where a reasonably high:

speed is maintained and no special precautions are taken,• such as coasting down hills, etc., in order to obtain the best figure humanly possible. In order to obtain some idea of the figures that are being attained with vehicles in everyday service it would perhaps be as well at this juncture to quote a few examples obtained by calculation from the Tables of Operating Costs that appeared in the issue of Me Commercial Motor for March 20th. Certain instances might be improved upon considerably, but in the main the figures quoted may be taken as being representative of the vehicles in each of their respective classes.

For ordinary vans or lorries on pneumatic tyres -a onetonner should giv.0 15 m.p.g., a two-tonner 11 m.p.g„ and a five-Limner 7 m.p.g. A ten-ton articulated six-wheeler on solids should record regularly 5 m.p.g., whilst with a twelvetwiner on pneumatics 4.5 m.p.g. should be obtained. Rigidframe six-wheelers follow very much upon the four-wheel type with, perhaps, a little advantage for the former. With buses, consumption figures are, of course, complicated by the number of stops that are enforced by virtue of the exigencies of the service; consequently, reliable " average " figures on this score are difficult to obtain. A 32-passenger, rigid-frame six-wheeler should be capable of about 9 m.p.g., a 48-passenger vehicle somewhere in the neighbourhood of

m.p.g. and a 72-passenger bus 6.5 m.p.g. or thereabouts.

Motor coaches are, of course, on rather a better footing, for they run continuously with few stops. On the other hand, the speed at which they normally travel is, of course, very much higher than that of the bus, with the result that the consumption figures are proportionately increased. Thus, it will be seen that the two types of vehicle may quite easily be very similar in consumption of fuel.

The foregoing has been included to give an idea of what is generally obtained in practice. If the results of any operator are as good as, or better than, the figures given, it would seem to be inopportune for him to worry about increasing efficiency to any marked extent. It is just possible, though, that a slack period may give the opportunity for carrying out research work and experimenting with various carburetter and ignition settings. It is not proposed to deal here with such straightforward, but wasteful, items as lack of care in filling up, looseness of the joints in the pipe. lines (although the writer has discovered many cases where

such defects are common) but to focus attention upon the more important problemsin efficiency maintenance that are occasioned by weal', lack of adjustment and other untoward causes.

. It is difficult to know exactly where to start in order to spot any inefficient component, as the symptom of each particular " disease " varies so enormously ; thus a gradual falling off in efficiency may mean that wear of some important component has taken place, whereas. a sudden drop in the m.p.g. figure may often indicate a breakage. One of the most frequent causes of excessive consumption is wear of the float-chamber needle, for the tapered part of the needle forming the valve may have become stepped. Normally the valve will seat properly, but so soon as the engine is started, and especially when the vehicle is on the move, road vibration COE11.birred with engine vibration causes the needle to float with one edge of the step in the valve Overlapping its seat in the float chamber. Thus, whilst there is no apparent leakage, the mixture is enriched throughout the whole speed range of the engine ; the remedy is obvious but as it is apparently sucha trivial item it is often overlooked.

Another rather obscure cause of excessive consumption of fuel occasionally lies in the shape of the induction pipe. This' is not necessarily meant to imply that the induction system itself is badly designed (although in certain instances this is So), but rather that a faulty casting may have escaped the notice of the inspection department of the manufacturers. One case is of particular interest. The engine of a three-ton lorry would pull quite satisfactorily for short distances, but intermittently the power would suddenly fall off, although no misfiring took place. This happened at irregular intervals, but always upon opening up after easing the throttle for a time. After a great deal of investigation, the induction pipe was examined very carefully, when it was discovered that the core for the hori-_ zontal part of one of the branches (feeding two cylinders, by the way) had apparently dropped, leaving a hollow in what should have been a perfectly straight passage: In this hollow, pools of petrol collected which, in the words of the mechanic employed, "went into the engine occasionally in dollops.' " A new induction pipe improved

the engine out of all recognition.

It is .seldom appreciated by the average user how important correct and suitable valve timing is to the performance of the engine. Igni..tion timing, too, is extremely important, and if either, or both, are slightly out of tune the consumption of fuel for a given output of power may quite easily be increased by r."25 per cent. This SguIrt represents a big outlay if a whole fleet of vehicles be similarly out of adjustment when taken over a year's running.

Valve timing is a muchdebated matter, and there can be given no set rule for obtaining maximum efficiency in any of a number of engines. The whole question is so wrapped up with port sizes and the rate of change of acceleration in both the lift and fall of each valve that the engine manufacturer must be considered as the only reasonable source from which information can be obtained.. Many people make a point of setting the valve timing from the exhaust-closing and inlet-opening positions. Whilst these points are of some importance, they fade into insignificance when compared with the inlet-closing position. It is a well-known fact that the momentum of the gases (which are, of course, rapidly moving when the piston has reached a point about half-way down its stroke) is used in order completely to' fill the cylinders. The means adopted is to allow the inlet valve to remain open for a portion of the time when the piston is actually ascending on its compression stroke.

Now, this is the important point. The two increases in pressure—one, the increase derived by virtue of the momentum of the gases and, the other, the internalincrease .(as it were) due to the reduction in volume of the gas space caused by the rising piston—must balance out at the point where the inlet calve closed. Engine speed is, of course, a relative quantity, but the balance should obtain during a time when the engine is running at its most efficient and mostly used speeds.

The argument may be raised that any inefficiency due to this cause would not necessarily entail increased fuel eonsumption. A little reflection, however, will show that it would. Thermal efficiency is dependent upon compression ratio, and, if the inlet valve closes too early the virtual compression pressure will, of course, be lower, owing to the fact that the cylinders have not been completely filled. Again, the inlet opening may be on the early side, which would leave a residual portion of the exhaust gases in the cylinder. Whilst it is known that a little exhaust diluent in the inlet gases is beneficial so far as. the avoidance ofpinking is concerned, efficiency is cut down to. a certain extent.

After an engine has been in use for a considerable period it will most probably be found that it is impossible to make the opening and closing of the valves coincide with the points on the timing diagram supplied by the manufacturers of the engine. If there be any material difference it is an economy to purchase a new camshaft or at least have the worn eamshaft "stoned."