The two-wheeler truck market is dominated by 7.5 and 17

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

tanners. If EC proposals to make HGV licences compulsory at 3.5 tonnes come in, AWD's TL 1 3-1 6 will fill the breach.

IN Just where would the 1950s British film be without the truck? Crucial to the plot of Hell Drivers (1958), and equally important to the final scene of Hue and Co) (1950), where a truck turns over and allows Alastair Sim's "rambunctious youths" to run amok. Not that it can be just any truck. In the first place it must belong to the local baker, or butcher. Then the truck must be a rigid, and small enough to get onto the film set; say 13 tonnes gross weight. It's no use just putting any old driver behind the wheel either. It must be a thin, weasely individual, with a pinched roll-up on the upper lip and, of course, a dirty flat cap.

Trucks like this seem to have died a death in the past few years. Admittedly, the market at 7.5 tonnes is full of such vehicles, but they will be flashing past you on the motorway, a steely-eyed car licence holder at the wheel. Similarly, the opposite end of the scale is the 17-tonne vehicle. Scintillating in a gaudy livery, shining alloy wheels, and every effort made to cram the very last gramme of load onto four wheels. They too seem to have a permanent dispensation from the 961rm/h (60mph) motorway speed limit.

So where are the in-betweenies? The little honest trucks plying their trade round the country's A-roads? The truth is that they have been squeezed out. No one wants to employ an expensive HGV 3 driver and then use those skills with a vehicle four tonnes under the driver's capacity. Only 2,717 12 to 15-tonne trucks were sold in the UK by the end of September, which compares with 15,749 7.5-tonners, and 10,007 over 15-tonners. This means that 7.5-tonners hold 45.3% of the two-axle market, over 15-tormers hold 28.79% of the same, and 12 to 15tonners represent a humble 7.8., of the 34,757 two-axle trucks sold in the UK to the end of September. Even the film companies only seem to want 50-tonne monsters to overtake cars, or knock down walls nowadays. Come back the Ealing comedy, all is forgiven.

All is not completely lost for the inbetweenies, however. If the European Commission's proposals for HGV tests starting at 3.5 tonnes (CM 26 October-1 November) come in, the choice of vehicle may start to reflect the operator's needs, rather than what licence the driver has. The whole market from 3.5 to 17 tonnes will be thrown wide open by such a move, and the 7.5-tonne mountainous sales figures will suffer a considerable land slip.

Which vehicle would you choose under these circumstances? An 11-tonner with 100kW? A 15-tonner with 130kW? Or would it be this week's test truck, a 13tonner with 119kW (160hp)? AWD's Boscombe Road mob have put their money into the' in-between categories, and offer a range of trucks based on the TL cab of between 6.5-tonnes, and 17-tonnes gross weight, all with special chassis built to suit the weight category.

There are six weight ranges: seven, eight, nine, 10, 12, 13 and 17 tonnes, all with Perkins Phaser engines of different powers. With Bedford's heritage behind them, the AWD TL vehicles must hold the Passport to Pimlico, and an Equity card for all those film roles where a baker or butcher's lorry is needed to trundle on and off film sets.

• EXTERIOR

AWD has done its best with the old TL cab. New panels adorn most surfaces, and the treatment of the front bumper, with spotlamps, is particularly good. We have been promised new mirror brackets for some time now, and the joke about the mirror that pulls the door open at speed is wearing a bit thin.

The AWD's body payload of 9,118kg is impressive when compared with the Steyr I3S18, which has a gross weight of 12.7 tonnes. Not so impressive though is the tolerance of 370kg, which means that loads must be carefully organised to avoid overloading the front axle. AWD's engineers have apparently been asked if they could increase the capacity of the front axle. This would boost the vehicle's appeal to a market that is not supremely knowledgeable about loading lorries, and could fall foul of the small loading tolerance on the front axle.

To finish off the roof line, AWD has fitted a little roof spoiler, which would be fine for speeding air flow over a Wendy House, but does little to improve the aerodynamics of the Boalloy van body fitted to the test vehicle.

• PERFORMANCE

The Perkins Phaser 6.160T blown sixcylinder in-line diesel produces 119kW (160hp) at 2,600rpm, and 516Nm (381113f0 of torque at 1,600rpm. We are pleased to see that the green sector on the revcounter bears a closer approximation to the usable torque of the engine than on the 13-tonner's big brother, the 17-18.

It is a very old fashioned exhaust note that greets the driver on starting the engine, and its presence is noticed at every speed. The unit's performance is hardly shattering, but it is more than enough for local deliveries. On motorways it cracks the 961(mih (60mph) barrier, but small hills slow it quickly.

The Eaton 4106 gearbox has replaced the Spicer T5-35216 five-speed allsynchromesh box. Six speeds are better than five, although we have our reservations about this gearbox. The gearbox is a revelation to those used to meeting it in heavier applications like 17 tonnes. The linkage to the gear lever is clear cut, and strong detent springs help gear selection The shift quality may be notchy as a re stilt, but there is never any doubt abou which gear you are in.

Our only complaints are with the choio of sixth ratio, which is a little optimistic and a third gear synchromesh that can bi caught napping. Like most examples c the Eaton 4106 we have come across, thi gear teeth heartily thank a driver will double-declutches up the box. The clutch fitted is a ceramic and metal single-plate unit. Other units we have tested of this type can be a little abrupt on occasions. We never had cause for complaint with this unit, and hill starts were very easy to effect. At the rear, a single-speed, hypoid AWD axle diverts the drive out to the rubber.

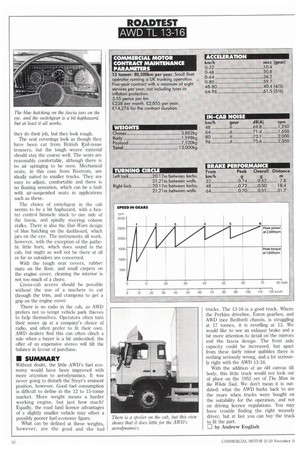

II ECONOMY

We haven't tested many 13-tonners but the latest was the Steyr 13S18 (CM 29 June-5 July). This was a more powerful truck than the AWD, and it carried 300kg less gross weight. Around our Welsh route the Steyr gave a respectable 20.91it/ 100km (13.53mpg), compared with the AWD's 21.761it/100km (12.98mpg).

The AWD got round our Welsh test route with an average speed of 64.42krn/h (40.03mph). The Steyr was much slower, despite its more powerful engine, at 54.87km/h (34.18mph). The other comparisons are used to give an idea of the spread of fuel consumptions in the 12 to 15-tonne vehicle parc. It pays to know what you are buying, before you have to pay for the fuel.

• HANDLING

AWD has fitted anti-roll bars at the front and rear of the 13-16. Two bars will set a potential owner back £299 (ex-VAT), and never was money better spent. The result is almost roll-free handling, with reasonable comfort on bumpy roads. In fact, the little truck can be literally hurled at a corner, and its flat handling gives an onlooker no idea of the panic going on in the cab.

The steering is light, and there is adequate lock. We did notice an odd tendency to track along the ruts created by HGVs on the motorway and we wondered if we were going to be able to turn off for Aust services at the Severn bridge. We can only conclude that a combination of the Dunlop SP 331 275/70R radial tyres and the steering system combined to stick the truck to ruts like glue. It didn't happen again on the test.

In fact, this behaviour was in sharp contrast to the vehicle's performance when crossing the Severn bridge, where the waters beneath heaved and boiled. A purple light and the surging swell ominously predicted storms, and there was a strong cross wind. The truck never deviated from its course, so there is no shortage of stability from the little 13-tonner. Perhaps the M4 is due for some resurfacing?

AWD tells us that an exhaust brake is on its way for this vehicle. While the brakes provide drama-free stopping, we would like to see an exhauster as well. It would increase a driver's confidence on long downhill runs and also save the brake linings.

• INTERIOR

There are lots of pockets, and there is a useful shelf above the windscreen, but the TL cab is still cramped. The third seat in the cab keeps things a bit hectic on the storage-space front, although the little shelf behind the seats helps to swallow up some of the detritus.

The problem is the lack of room for ropes, jacks, lamps and the dirty, greasy tools of the trade. Leyland Daf has solved this problem with a passenger foot rest that doubles as a tool box. AWD could do the same.

Apart from the wobbly mirrors already mentioned, there were one or two groans from the cab when the ride and handling circuit at the Motor Industry Research Association's proving ground was inflicted on its delicate sensibilities.

There is also a slight air of Eastern-bloc trim levels around the door and window; they do their job, but they look rough.

The seat coverings look as though they have been cut from British Rail-issue trousers, but the tough weave material should stay the course well. The seats are reasonably comfortable, although there is no air springing to be seen. Mechanical seats, in this case from Bostrom, are ideally suited to smaller trucks. They are easy to adjust, comfortable and there is no floating sensation, which can be a fault with air-suspended seats in applications such as these.

The choice of switchgear in the cab seems to be a bit haphazard, with a heater control binnacle stuck to one side of the fascia, and spindly steering column stalks. There is also the Star Wars design of blue hatching on the dashboard, which jars on the eye. The instruments all work, however, with the exception of the pathetic little horn, which does sound in the cab, but might as well not be there at all as far as outsiders are concerned.

With the tough seat covers, rubber mats on the floor, and small carpets on the engine cover, cleaning the interior is not too much of a chore.

Cross-cab access should be possible without the use of a machete to cut through the trim, and crampons to get a grip on the engine cover.

There is no radio in the cab, as AWD prefers not to tempt vehicle park thieves to help themselves. Operators often turn their noses up at a company's choice of radio, and often prefer to fit their own. AWD dealers find this can often clinch a sale when a buyer is a bit undecided; the offer of an expensive stereo will tilt the balance in favour of purchase.

• SUMMARY

Without doubt, the little AWD's fuel economy would have been improved with more attention to aerodynamics. It was never going to disturb the Steyr's eminent position, however. Good fuel consumption is difficult to define in the 12 to 15-tonne market. More weight means a harder working engine, but just how much? Equally, the road fund licence advantages of a slightly smaller vehicle may offset a possibly poorer fuel economy figure.

What can be defined at these weights, however, are the good and the had

trucks. The 13-16 is a good truck. Where the Perkins driveline, Eaton gearbox, and AWD (nee Bedford) chassis, is struggling at 17 tonnes, it is revelling at 13. We would like to see an exhaust brake and a bit more attention to detail on-the mirrors and the fascia design. The front axle capacity could be increased, but apart from these fairly minor quibbles there is nothing seriously wrong, and a lot seriously right with the AWD 13-16.

With the addition of an old canvas tilt body, this little truck would not look out of place on the 1952 set of The Man in the White Suit. We don't mean it is outdated: what the AWD harks back to are the years when trucks were bought on the suitability for the operation, and not on driving licence regulations. You may have trouble finding the right weasely driver, but at last you can buy the truck to fit the part.

CI by Andrew English