8mpg harrier breaker

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

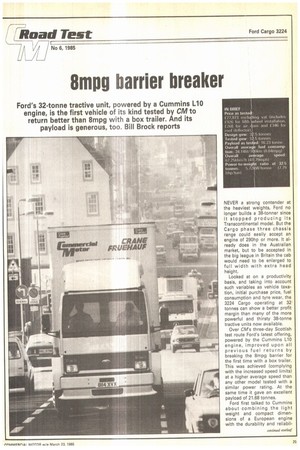

NEVER a strong contender at the heaviest weights, Ford no longer builds a 38-tonner since it stopped producing its Transcontinental model. But the Cargo phase three chassis range could easily accept an engine of 290hp or more. It already does in the Australian market, but to he accepted in the big league in Britain the cab would need to be enlarged to full width with extra head height.

Looked at on a productivity basis, and taking into account such variables as vehicle taxation, initial purchase price, fuel consumption and tyre wear, the 3224 Cargo operating at 32 tonnes can show a better profit margin than many of the more powerful and thirsty 38-tonne tractive units now available.

Over CM's three-day Scottish test route Ford's latest offering, powered by the Cummins L10 engine, improved upon all previous fuel returns by breaking the 8mpg barrier for the first time with a box trailer. This was achieved (complying with the increased speed limits) at a higher average speed than any other model tested with a similar power rating. At the same time it gave an excellent payload of 21.68 tonnes.

Ford first talked to Cummins about combining the light weight and compact dimensions of a European engine with the durability and reliabil ity recognised in North American engines, back in 1976.

In the form used by Ford the LW engine produces maximum power of 186kW (250hp) at 2,100rpm and maximum torque of 1,1 0 7Nm (7 5 Olbft) at 1,300rpm. It is mounted vertically, but is still low enough to fit beneath the same low floor panel that was engineered to suit the Perkins V8.640 engine specification as the standard option for operation at 28 tonnes gross vehicle weight.

Although the Cummins engine is located cq)se to the underside of the cab, noise emission from the head is so low that no extra insulation has been added. In-cab noise levels are as low as 7 6dBIA) at 2,100rpm in sixth gear. The chassis, bellied between the axles, is unflitched but has room for the engine to fit comfortably. With the tubular crossmembers passing below, access from above is unrestricted.

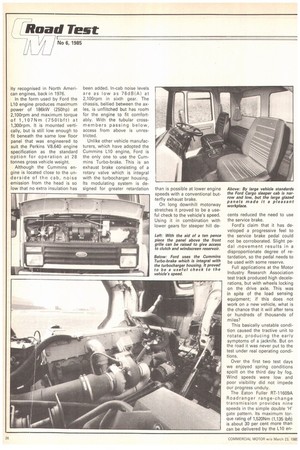

Unlike other vehicle manufacturers, which have adopted the Cummins L10 engine, Ford is the only one to use the Cummins Turbo-brake. This is an exhaust brake consisting of a rotary valve which is integral with the turbocharger housing. Its modulating system is designed for greater retardation than is possible at lower engine speeds with a conventional butterfly exhaust brake.

On long downhill motorway stretches it proved to be a useful check to the vehicle's speed.

Using it in combination with lower gears for steeper hill de cents reduced the need to use the service brake.

Ford's claim that it has developed a progressive feel to the service brake pedal could not be corroborated. Slight pedal movement results in a disproportionate degree of retardation, so the pedal needs to be used with some reserve.

Full applications at the Motor Industry Research Association test track produced high decelerations, but with wheels locking on the drive axle. This was in spite of the load sensing equipment; if this does not work on a new vehicle, what is the chance that it will after tens or hundreds of thousands of miles?

This basically unstable condition caused the tractive unit to rotate, producing the early symptoms of a jacknife. But on the road it was never put to the test under real operating conditions.

Over the first two test days we enjoyed spring conditions spoilt on the third day by fog. Wind speeds were low and poor visibility did not impede our progress unduly.

The Eaton Fuller RT-11609A Roadranger range-change transmission provides nine speeds in the simple double 'H' gate pattern. Its maximum tor que rating of 1,520Nm (1,135 lbft) is about 30 per cent more than can be delivered by the L10 en gine, but it carries little weight penalty. Indeed, it weighs 290kg (6401b) complete with clutch housing and oil.

Multimesh gearing quietens the running of this constantmesh gearbox, while improved synchronisers and the corrosion-resistant air valve increase the durability of the unit.

Gear selection is positive and, due to the lugging power of the engine and ratio overlap of the gearbox, allows the driver to miss alternate gears during down-changes. This is particularly useful when negotiating the harder hill climbs.

Allowing the engine to pull down over its full working range or changing earlier to keep the engine at higher revs had little overall effect on fuel consumption over less taxing sections of our route.

Integral power steering is standard equipment as is the front anti-roll bar. The steering wheel rake and height are adjustable and locked in position by a pretensioned clamp. Feedback through the small steering wheel is typical of a smaller vehicle, failing to match the sure-footed feel expected of a maximum weight truck.

Bostrom Viking 411/1 suspension seats are provided for driver and passenger. Hydraulic damping can be set to accommodate weights from 50 to 120kg (110 to 260Ib). In the absence of a sprung cab they compensate well when the vehicle encounters anything but the smoothest of road surfaces. surfaces.

The cab is less than full width, but in sleeper version with one bunk is roomy for all that. It has a lot of glass which, while good for all-round visibility, adds to the weight of construction, heats the cab up quickly in sunny conditions and equally dissipates heat in cold weather.

The roof is low and most drivers would find difficulty in standing upright as they prepare for a night's sleep. The floor panel is covered by about 37kg of high density mat which has proved wholly successful as a noise deadening medium.

As it weighs about 163kg (360Ib) more than the day cab, a hydraulic lift pump supplements existing torsion bars to raise the sleeper cab to either of its two tilt positions.

Inside cab trim in red and black is pleasing to the eye. The door trim includes pouches for paper work, but extra stowage for more substantial items is provided below the bunk.

Brake and gear levers are stubby but easy to use. Instrumentation, well displayed, is housed in a dished binnacle in front of the steering wheel. Heater controls are simple and easily adjusted. My only complaint concerning controls is the position of the dash mounted headlamp switch, which I have no doubt Ford is already in the process of relocating.

A power-to-weight ratio of 5.72kW/tonne (7.79hp/ton) is no longer considered high, but is sufficient to provide adequate acceleration and maintain maximum motorway cruising speeds with a full load over long distances. There is no substitute for power when it comes to hill climbing, but sometimes an intermediate gear helps to maintain speed.

However, the 3224's performance with only nine gears was about average when measured over a range of hills. Over more normal terrain the engine pulled comfortably at about 1,800rpm at 60mph on the motorway. Top gear at 50mph corresponds to about 1,500rpm. While maximum torque occurs at 1,300rpm, the engine pulls well down to 1,000rpm.

Unlike any other exhaust brake I have used, the Turbobrake gave a near consistent performance over the useable engine-speed range. Its most endearing quality was not, however, its stopping power — it was its ability to roll freely. This, perhaps above all else, was the reason for the vehicle's good fuel returns helped, no doubt, by its small frontal area and overall profile.

It is more than 12 months since CM last tested a vehicle at 32.5 tonnes. Even allowing for the increase in speed limits to 50mph on dual carriageway, which we believe results in more economical running, to have achieved over eight miles to the gallon is a quantum jump in performance. On a tonne-per-mile fuel cost basis it becomes competitive with the heavier 38-tonne class vehicle — especially considering the lower level of purchase price and excise duty.

Although it is the quickest vehicle we have tested at 32.5 tonnes over the route, the Cargo's journey times are slower than most of the more powerful 38 tonners. Comparing like with like, however, it performs well on all counts and will provide an economical alternative to many existing 28 tonners also.