Delivering the goods on time

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

it was not happening for Shippams until the company hired Low-field and things improved. David Wilcox reports. MANUFACTURER faces 3veral choices when condering how he will distribute is product. Once he has opted )rroad transport — and most o — his alternatives are to run is own transport fleet or to call

an outside carrier.

Shippams of Chichester, the meat and fish paste manufacirer, is one firm which has tried averal systems and eventually ?Wed, by trial and error, for an utside specialist.

Shippams is a longstablished firm (since 1750) wit its premises on the South :oast presented problems no latter what form of distribution as adopted. Some of the cornony's Scottish customers, for )carnple, are more than 600 rifles distant from the factory.

The man responsible for geting Shippam's yearly producion of 16,500 tons of paste rom its Chichester, West Sus:ex factory to the High Street :hops is distribution manager 3arry Houlston.

Up until the mid-1960s 3hippams had relied almost enirely on the railways for its disribution. This had just evolved vithout any real study of the ;ompany's requirements. But 3hippams found that with a ligh number of split deliveries, :he railways took too long to Jeliver the goods, which was lindering sales.

So the company switched to a road-based system and 3mployed some 18 different Iocal carriers throughout the country. They were picked only through local contacts, not as a result of any careful study, and Mr Houlston told me that they were frequently changed!

As a result of the non-stock system, within a few years Shippams again found that delivery times were too long and the sales side of the company felt that the distribution was letting it down. The 18 local carriers had not brought about any real improvements, said Mr Houlston. -It was just making the best of a bad job". Until then the distribution of the pro

duct had not been logically planned — it had just evolved and "grew like Topsy!"

To put this right, in 1974 Shippams formed a distribution improvement committee, with representatives from the company's manufacturing, sales, accountancy and transport departments. It decided to throw out the old distribution methods and start afresh.

It decided first that the old railway system of individually addressed parcels must go — it lacked flexibility. So Shippams decided to adopt the coding system, with each product linecoded and the orders being made up by the local distributor.

The committee was split over who should do the distribution. "Some members wanted to retain the various different local carriers in order to avoid having all the eggs in one basket," said Mr Houlston. Others wanted to contract just one nationwide carrier, offering the advantages of simplification, a national rate and easier administration and accounting. This course of action carried the day. But who should the carrier be?

Shippams invited representatives of several large carriers to Chichester. One of these carriers, and one of the smallest, was Lowfield Storage and Distribution, based at Daventry in Northamptonshire. Lowfield is part of the Imperial Food Group and had been formed only five years before to distribute Imperial food products, firstly Golden Wonder crisps and then Smedley HP foods. It was branching out into non-group business and, though small, was able to offer the nationwide distribution Shippams required.

Its relative smallness attracted Shippams. Mr Houlston said Lowfield offered a personal touch: "Shippams felt that it could get along with Lowfield and mean something to them."

Trunking

The location of Lowfield depots also suited Shippams. The company wanted an optimum number of stock-holding depots, yet the minimum number to give good distribution service. Lowfield could achieve this by carrying out inter-depot trunking: Shippams would trunk to the key stockholding depots and Lowfield would trunk the goods onward to the remaining depots as and when needed.

Shippams decided to give Lowfield a trial and in April 1975 distribution of Shippams products was gradually taken on by Lowfield.

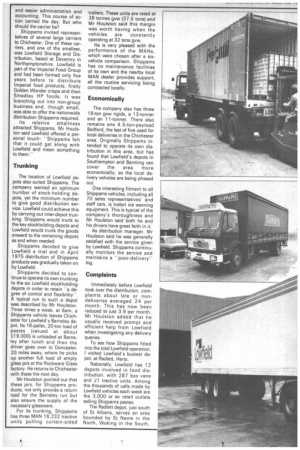

Shippams decided to continue to operate its own trunking to the six Lowfield stockholding depots in order to retain "a degree of control and flexibility". A typical run to such a depot was described by Mr Houlston. Three times a week, at 6am, a Shippams vehicle leaves Chichester for Lowfield's Barnsley depot. Its 18-pallet, 20-ton load of pastes (valued at about £19,000) is unloaded at Barnsley after lunch and then the driver goes over to Doncaster, 20 miles away, where he picks up another full load of empty glass jars at the Rockware Glass factory. He returns to Chichester with these the next day.

Mr Houlston pointed out that these jars, for Shippams products, not only provide a return load for the Barnsley run but also ensure the supply of the necessary glassware.

For its trunking, Shippams has three MAN 16.232 tractive units pulling curtain-sided trailers. These units are rated at 38 tonnes gvw (37.5 tons) and Mr Houlston said this margin was worth having when the vehicles are constantly operating at 32 tons gvw.

He is very pleased with the performance of the MANs, which were chosen after a sixvehicle comparison. Shippams has no maintenance facilities of its own and the nearby local MAN dealer provides support, all the routine servicing being contracted locally.

Economically

The company also has three 16-ton gvw rigids, a 13-tonner and an 11-tonner. There also remains one 4.5-ton-payload Bedford, the last of five used for local deliveries in the Chichester area. Originally Shippams intended to operate its own distribution in this area, but has found that Lowfield's depots in Southampton and Barming can cover the area more economically, so the local delivery vehicles are being phased out.

One interesting fitment to all Shippams vehicles, including all 70 sales representatives' and staff cars, is lcelert ice warning equipment. This is typical of the company's thoroughness and Mr Houlston said both he and his drivers have great faith in it.

As distribution manager, Mr Houlston said he was generally satisfied with the service given by Lowfield. Shippams continually monitors the service and maintains a "poor-delivery" log.

Complaints

Immediately before Lowfield took over the distribution, complaints about late or nondeliveries averaged 24 per month. This has now been reduced to just 3.9 per month. Mr Houlston added that he usually received prompt and efficient help from Lowfield when investigating any delivery queries.

To see how Shippams fitted into the total Lowfield operation, I visited Lowfield's busiest depot, at Radlett, Herts.

Nationally, Lowfield has 12 depots involved in food distribution, with 287 box vans and 21 tractive units. Among the thousands of calls made by Lowfield vehicles each week are the 3,000 or so retail outlets selling Shippams pastes.

The Radlett depot, just south of St Albans, serves an area bounded by St Neots in the North, Woking in the South, Chelmsford in the East and Witney and Newbury in the West.This also includes London, the most complex delivery area.

There are 40 box vans based at Radlett, Hens, a mixture of 16and 13-ton-gvw Fords and Dodges. Three tractive units and four box trailers are used for the inter-depot trunking already mentioned and the larger bulk deliveries.

Perspective

Radlett's 40 box vans make a total of 2000, calls per week, delivering about 150,000 cases. To put the Shippams side of the business in perspective, of these 2,000 calls 120 are Shippams deliveries, taking some 3,700 cases.

The rest of Lowfield's traffic is made up of Imperial Food Group products, plus other non-group products like Shippams pastes from companies which include Lyons Tetley, General Foods, Adams Biscuits, Food Brokers and Plum rose.

I asked Lowfield's South East regional manager Brian Riley how, when Shippams business was clearly such a small part of the company's total traffic, Lowfield managed to make Shippams feel such an import ant customer. • Mr Riley immediately stressed that all the company's clients were treated equally, both group and non-group business. "Lowfield is a professional carrier — not the distribution fleet of Imperial Foods taking on some other work as a side line."

Like Mr Houlston, Mr Riley also felt that Shippams and Lowfield worked well together. He attributed this partly to the Shippams products themselves; having confidence in the products you distribute helps a great deal.

Convenient

Lowfield drivers also liked handling Shippams pastes because of the good marking of the codes, their convenient volumeto-weight ratio and their ability to be easily stacked.

As Lowfield continues to grow, Mr Riley was confident that the company could still offer that personal touch that Shippams valued.

The growth record of Lowfield Storage and Distribution is notable. Starting from scratch just nine years ago, it is now one of the top distribution companies in the country.

Its 12 depots were strategically sited close to a motorway or main trunk road. This means that drivers can cover "dead" mileage to reach their delivery areas as quickly as possible.

Lowfield follows a one-man, one-vehicle policy as much as possible. A driver loses his allocated vehicle only for servicing or when it is too tall for a height restriction on a particular delivery route.

Drivers also tend to specialise in deliveries to one or two particular areas, where they can develop a local knowledge and get to know all the regular calls. So when a manufacturer contracts his distribution to a carrier, he also reaps this benefit of the drivers' experience and knowledge.

In its nine-year life, Lowfield has won contracts from nongroup customers. The most recent of these is from Food Brokers, a company which markets a wide range of grocery products. Brokerage is a rapidly growing business in Britain and promises big things for its carrier,

-More non-group business means that we can integrate deliveries of more products, and it's this that provides the economies that are the basis of

professional distribution, Therefore as we grow, we can provide a better service which benefits our clients, who should be able to grow with us," said Mr Riley.

Relationship

This shows how the prosperity of the manufacturer and his carrier depends on each other, and why a good working relationship between them is so important. Mr Riley added that the growth of Lowfield Distribution would never be made at the expense of the personal touch it could offer, and that was valued so much by Shippams.

After looking at Shippams' distribution system, it would seem that the company had finally reached the best type of distribution for its particular needs. As Mr Houlston showed with his delivery complaint figures, it is certainly better now than it has ever been in the past.

The object of the original distribution improvement committee was to achieve a good distribution to back up a good and successful product. Quality of distribution was foremost — "it was not a cost-cutting exercise" said Mr Houlston, Shippams is not resting on its laurels. With that 229-year-old reputation in mind, the distribution improvement committee still aims to improve further,