RAIL TO THE HELP OF ROAD?

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BY

P. A. C. BROCKINGTON, AMIMechE IF expenditure on braking equipment by road vehicle manufacturers was proportionate to the amount spent by the builders of rail vehicles, the equipment would cost at least five times as much. Of course, the equipment would be more efficient, more reliable and last longer. The makers of rail equipment are given appropriate latitude to produce systems that comply with the best interests of the user and if this had been symptomatic of the road-vehicle industry there would have been no need for special legislation to ensure adequate braking standards.

Davies and Metcalfe Ltd., of Oswestry, Shropshire and of Romily, near Manchester, have been producing braking equipment for rail vehicles for over 100 years, and about 12 months ago opened a road brake division at Oswestry. The views quoted are based on comments made by Mr. J. P. Metcalfe, chairman of the company and joint managing director, who considers that certain systems evolved for rail vehicles could with benefit be applied in modified form to road vehicles, notably anti-locking equipment monitored from change of wheel speed.

Concerned with immediate practical problems created by the new regulations, Mr. R. S. Hyde, manager of the road brake division, and formerly senior development engineer of the Dunlop disc brake division, is in general agreement with these views but emphasizes that the regulations are in the main "aimed at operators who neglect maintenance", the vehicle maker who builds down to a cost or has done so in the past being a secondary if important transgressor in the overall scene. The company have been producing original equipment of the direct air-operated type for a number of trailer makers since the inception of the division and for a shorter period have been supplying conversion kits for a variety of vehicles direct to operators. It is significant that this business is now 10 per cent of the total and is increasing rapidly.

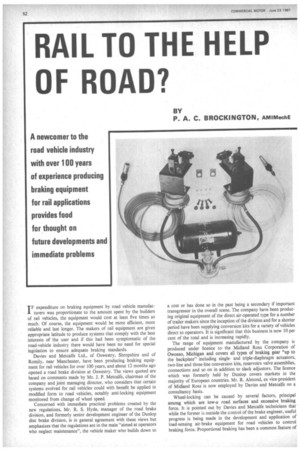

The range of equipment manufactured by the company is produced under licence to • the Midland Ross Corporation of Owosso, Michigan and covers all types of braking gear "up to the backplate" including singleand triple-diaphragm actuators, two-line and three-line conversion kits, reservoirs valve assemblies, connections and so on in addition to slack adjustors. The licence which was formerly held by Dunlop covers markets in the majority of European countries. Mr. R. Almond, ex vice-president of Midland Ross is now employed by Davies and Metcalfe on a consultancy basis.

Wheel-locking can be caused by several factors, principal among which are low-m road surfaces and excessive braking force. It is pointed out by Davies and Metcalfe technicians that while the former is outside the control of the brake engineer, useful progress is being made in the development and application of load-sensing air-brake equipment for road vehicles to control braking force. Proportional braking has been a common feature of railway systems for many years and has reached a high degree of sophistication as evidenced by the success of British Railways Freightliners. Employing an axle-mounted inertia-wheel antilocking system is now a common railway practice which could profitably be applied, in Mr. Metcalfe's view, to road vehicles, particularly heavier units.

While the main purpose of preventing the wheels of a train from locking is to obviate flats on the steel tyres, the effectiveness of the system is proof of its performance, and to indicate its sensitivity to changing conditions. Mention is appropriate in view of its use to aid traction of the locomotive by preventing excessive wheel spin. In the event of spin, a braking-force is automatically applied to reduce the r.p.m. of the wheels to that corresponding to the forward speed of the locomotive.

Load sensing devices are included in the rail equipment produced by the company and the use of such devices is approved for road vehicle applications as an interim measure pending the development of a commercially-acceptable anti-locking system. In line with the thinking of the German BPW company it is considered that this would offer the only "complete solution" to the problem of automatically distributing the total braking force available according to variations in dynamic and static loading. It is pertinent that Mr. Metcalfe has a very high opinion of German brake design and standards of application. He notes, however, that design progress has been greatly helped by government legislation.

Much time and money has been spent on safety by the world's railways, and of potential interest to road vehicle makers is an electronic and vigilance apparatus developed for rail applications. The device has a run-down cycle preset to traffic conditions and on approaching run-down will give audible warning of pending operation. Failure to act on the part of the driver will, in the case of rail, apply the brakes or in the case of a road vehicle, could cut off the fuel and apply the brakes.

To avoid operation of the device, all the driver has to do is to carry out his duties in a normal and efficient manner, as by so doing all his normal actions relating to acceleration, deceleration, braking and so on will reset the vigilance cycle.

When equipment is supplied by the company to an operator to improve the efficiency of the service or auxiliary braking system to the standard stipulated in the regulations, the capacity of the actuators is matched to the brake torque rating specified by the vehicle manufacturer. A higher peak efficiency could normally be obtainable by employing actuators of higher capacity but this would involve the grave risk of early faults developing as the result of overheating, drum distortion, shoe fracture or failure of the suspension due to excessive wind-up.

Serious hazards

In some cases the foundation brakes have sufficient reserve torque capacity safely to permit an increase in torque, but this has to be verified by the manufacturer before equipment is supplied that provides for the increase. Mr. Hyde forecasts that operators who fit over-capacity actuators will "run into serious trouble" in the form of brake fade, drum crazing and rapid deterioration of the brake-drum assembly. The use of high-p brake linings could also, in Mr. Hyde's opinion, create serious hazards particularly if a high brake factor were a feature of the system. A typical co-efficient of friction is around 0.35 whereas the coefficient of a high-p lining is in the region of 0.38/0.39; the higher the brake factor the greater is the effect on overall braking efficiency of a reduction in friction resulting from fade.

In assessing the magnitude of the problems faced by operators of older vehicles, Mr. Hyde emphasizes that the possibility of raising the efficiency to the 1968 or 1972 standard is entirely dependent upon the latitude that exists between the torque that is applied and the torque that may be safely applied. Some immediate post-war vehicles could, for example, be modified to improve their efficiency from say 35/40 per cent to 50 or more per cent withct overloading the drums, but in other cases this would be impossible or unwise.

Drum diameter

With regard to new vehicles, Mr. Hyde points out that drum diameter is limited by the size of the wheel, and that in practice width is limited by the tendency of a wide drum to bell-mouth. A diameter of 154/16 in. is regarded as the maximum allowable for a

typical installation, the reduction in spring base necessitated by drums of more than a certain width being also a factor of importance. Obviously the use of larger wheels is a pre-requisite to combining an acceptable efficiency with reliability and long life.

Both Mr. Metcalfe and Mr. Hyde consider that the disc brake is the "ultimate" type for heavier road vehicles and Mr. Metcalfe points to the success of disc brakes fitted to Freightliners. The life of these brakes is many times the life of the standard type of clasp brake. As mentioned by Mr. Metcalfe, the brakes of a train set (weighing upwards of 1,000 tons) being brought to rest from a high speed are in continuous use for a far longer period than the brakes of a commercial vehicle in an emergency stop and the fact that heat dissipation problems have been overcome is of special significance.

Conversion sets

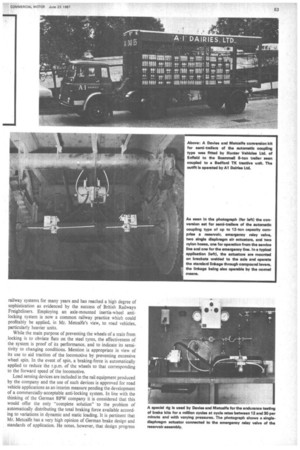

Conversion sets that have been supplied to operators of trailers of the automatic coupling type of up to 12-ton capacity, comprise a reservoir, emergency relay valve, two single-diaphragm actuators and two nylon hoses, one for operation from the service line and one for the emergency line. In a typcial application the actuators are mounted on brackets welded to the axle and operate the standard linkage through compound levers, the linkage being also operable by the normal means. The required braking force in a particular case can be obtained by selecting an actuator of the appropriate capacity and by positioning the pin holes in the lever arm to obtain a matching leverage. While an efficiency of 40 per cent is readily obtainable in the type of application mentioned, Mr. Hyde is doubtful whether a higher efficiency could be provided without overloading the drum assembly and possibly the suspension.

Auxiliary braking efficiency

An auxiliary braking efficiency of 30 per cent was obtained in the case of an Albion six-wheeled tipper (as checked by a Ministry of Transport examiner) by employing an air actuator controlled by a manually-operated valve in the cab to operate the existing handbrake linkage, the total cost of the equipment being £25. At an overall installation cost of less than £100, an AEC Mk. III eight-wheeler grossing at 234 tons was given an auxiliary brake efficiency of 35 per cent by using four triple-diaphragm actuators in conjunction with a protected reservoir to operate the brakes of the two rear axles. The cost of the equipment was about £60.

While it is impracticable if not impossible, in Mr. Hyde's view, to obviate fade on a long descent, it is essential that the brakes be capable of stopping a laden vehicle in an emergency with say not more than 10 to 15 per cent reduction in efficiency. Although the implementation of a "fade clause" in the regulations would present obvious difficulties, it is noteworthy that the German regulations stipulate a maximum allowable loss of efficiency under controlled conditions and this is regarded as a desirable safeguard that could well be emulated by the Ministry of Transport.