Problems of the HAULIER and CARRIER I THINK I made it

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

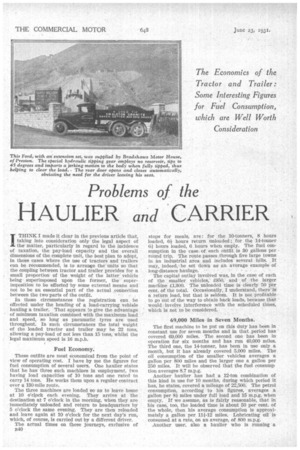

clear in the previous article that, taking into consideration only the legal aspect of the matter, particularly in regard to the incidence of taxation, the pay-load capacity and the overall dimensions of the complete unit, the best plan to adopt, in those cases where the use of tractors and trailers can be recommended, is to• arrange the units so that the coupling between tractor and trailer provides for a small proportion of the weight of the latter vehicle being superimposed upon the former, the superimposition to be effected by some external means and not to be an essential part of the actual connection between the two parts of the outfit.

In those circumstances the registration can be effected under the heading of a load-carrying vehisle hauling a trailer. That appears to give the advantage of minimum taxation combined with the maximum load " and speed, so long as pneumatic tyres are used throughout. In such circumstances the total wcight of the loaded tractor and trailer may be 22 tons, allowing a pay-load of not less than 15 tons, whilst the legal maximum speed is 16 m.p.h.

Fuel Economy.

These outfits are most economical from the point of view of operating cost. I have by me the figures for fuel consumption of several users. One haulier states that he has three such machines in employment, two having load capacities of 10 tons and one rated to carry 14 tons. He works them upon a regular contract over a 130-mile route.

The three machines are loaded so as to leave home at 10 o'clock each evening. They arrive at the destination at 7 o'clock in the morning, when they are immediately unloaded and return to headquarters by 5 o'clock the same evening. They are then reloaded and leave again at 10 o'clock for the next day's run, which, of course, is carried out by a different driver. .

The actual times on these journeys, exclusive of 1340 stops for meals, are: for the 10-tonners, 8 hours loaded, 64, hours return unloaded ; for the 14-tonner Oi hours loaded, 6 hours when empty. The fuel consumption in the case of each outfit is 30 gallons per round trip. The route.passes through five large towns in an industrial area and includes several hills. It may, indeed,. be set down as an average example of long-distance haulage.

The capital outlay involved was, in the case of each of the smaller vehicles, f950, and of, the larger machine f1300. The unloaded time is clearly 50 -Per cent of the total. Occasionally, I understand, there is a return load, but that is seldom. It is not profitable to go out of the way to obtain back loads, because that would involve interference with the scheduled tithes, which is not to be considered.

69,000 Miles in Seven Months.

The first machine to be put on this duty has been in constant use for seven months and in that period has covered 69,000 miles. The second one has been in operation for six months and has run 40,000 miles. The third one, the 14-tonner, has been in use only a month, but it has already covered 5,000 miles. The oil consumption of the smaller vehicles averages a gallon per 800 miles and the larger one a gallon per 250 miles. It will be observed that the fuel consump tion averages 8.7 m.p.g.

Another haulier has had a 12-ton combination of this kind in use for 10 months, during which period it has, he states, covered a mileage of 22,500. The petrol consumption, according to his figures, averages a gallon per 81; miles under full load and 15 m.p.g. when empty. If we assume, as is fairly reasonable, that in his case, too, the loaded time is about 50 per cent, of the whole, then his average consumption is approximately a gallon per 111-12 miles. Lubricating oil is consumed at a rate, on an average, of 800 m.p.g.

Another user, also a haulier who is running a

12-tonner which he has had in continual service for nine, months and in that time has covered 15,500 miles, reports a consumption at a rate-of 8 mpg. loaded and 15 m.p.g. empty, with lubricating oil at a quart per. 200 miles. His figures agree closely with those of the previous example.

A fourth operator whose business is chiefly the cartage of sand, ballast and road-making and building materials, and who habitually carries 13 tons or 14 tons, states that his consumption of fuel, when the outfit is loaded, is a gallon per 7.0 miles, but that when unloaded it falls to 19 m.p.g. That is equivalent to an average of 13.3 m.p.g.

Another user, who, unfortunately, does not give me actual figures for consumption, nevertheless remarks upon the obvious economy when running light.

These letters are authentic and the figures and facts they present are incontrovertible. There are certain special features made evident by these letters, which undoubtedly call for comment and consideration.

Big Mileages.

The first, which may possibly escape notice or, at least, not be appreciated at its full value, is the mileage which these vehicles are covering. The first example definitely relates to a contract which involves a minimum of 260 miles per day. The second one quotes a mileage which is equivalent to approximately 500 miles per week and the third is about the same.

These are performances which would not in the ordinary way be associated with tractor-trailer work. Indeed, the average pace of the heavier type of vehicle as exemplified in the first letter is nearly 22 m.p.h. There is, therefore, no doubt about the possibility of the user being able to take advantage to the full of the legal maximum limit of 16 m.p.h. I may add that I myself have investigated the working of a tractor-trailer outfit of this description and have observed its performance at speeds of about 30 m.p.h. The machine ran well and there was no difficulty whatever in negotiating a narrow winding country road along which one of my tests was conducted. One factor emerges most emphatically from this characteristic, namely, that the tractors I have in mind are not of the small converted agricultural type, which, although they undoubtedly have their uses—I hope to be able to refer to them later in this series—are obviously unfitted for the haulage of upwards of 12 tons at speeds up to and beyond the legal limit. The next point that I must discuss—for there is no need to draw attention to it—is the, fuel economy of vehicles of this type and particularly of the considerable difference in consumption which is noted as between that of a vehicle loaded and light.

think the latter aspect of the matter may be discussed in few words. It is surely due to the light weight of the vehicle as compared with its load capacity. If the gross weight be 22 tons and the net unladen weight under 7 tons, then the latter figure is < only a third of the former and a corresponding economy of fuel is to be expected.

The reason for the general economy is not perhaps so obvious. That it should be so, however, is suggested by the low tractive effort which machines of this type show when on test. Fitures of 15 lb. per ton have been given to me. They have been derived from independent tests, and compare with upwards of 30 lb., which is normally to be expected from the average motor vehicle carrying comparable loads. Incidentally, that these figures niay be relied upon is confirmed indirectly by what I have been told by tyre manufacturers in discussing the wear of pneumatic tyres on tractors, concerning which I shall have more to say anon. The wear is slight. In fact, one of our largest tyre manufacturers, which has had a tractor in use for some time, states that the tyres appear to be going to last indefinitely. That is a sure indication that the tractive effort needed is below the normal, although that is not the only reason for the longevity of the tyres.

A Reason for Tyre Longevity?

There is reason enough there, but readers will no doubt be curious, in company with myself, to learn whence this diminished tractive resistance arises.

The makers of these tractors are of the opinion that low tractive resistance is due to the fact that the rear axle does not have to support a load anything like commensurate with its strength, with that strength which is necessary to transmit the power. They state that in their view this fact eliminates the stress and strain to which the axle of an ordinary load vehicle is subject and thus eliminates some of the inefficiency of the transmission. S.T.R.