RECENT speculation on future weight limits prompted a brief visit

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

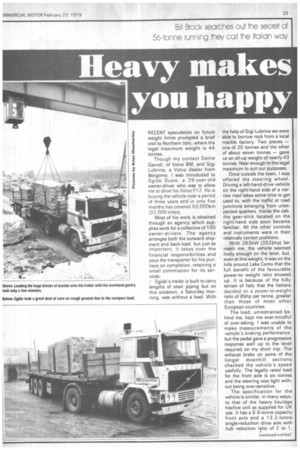

to Northern Italy, where the legal maximum weight is 44 tonnes_ Though my contact Dante Gavioli, of Volvo BM, and Gigi Lubrina, a Volvo dealer from Bergomo, I was introduced to Egido Dusio, a 29-year-old owner-driver who was to allow me to drive his Volvo F12. He is buying the vehicle over a period of three years and in only five months has covered 53,000km (32,000 miles).

Most of his work is obtained through an agency which supplies work for a collective of 150 owner-drivers. The agency arranges both the outward shipment and back-load, but just as important, it takes over the financial responsibilities and pays the transporter for his journeys on completion, retaining a small commission for its services.

Egido's trailer is built to carry lengths of steel piping but on this occasion, a Saturday morning, was without a load. With the help of Gigi Lubrina we were able to borrow rock from a local marble factory. Two pieces — one of 20 tonnes and the other of about seven tonnes — gave us an all-up weight of nearly 43 tonnes. Near enough to the legal maximum to suit our purposes.

Once outside the town, I was offered the steering wheel. Driving a left-hand-drive vehicle on the right-hand side of a narrow road takes some time to get used to, with the traffic at road junctions emerging from unexpected quarters. Inside the cab, the gear-stick located on the right-hand .side soon became familiar. All the other controls and instruments were in their relatively correct positions.

With 263kVV (352bhp) beneath me, the vehicle seemed lively enough on the level, but, even at this weight, it was on the hills around Lake Como that the full benefit of the favourable power-toweight ratio showed up. It is because of the hilly terrain of Italy that the Italians decided on a power-to-weight ratio of 8bhp per tonne, greater than those of most other European countries.

The load, unrestrained behind me, kept me ever-mindful of over-taking. I was unable to make measurements of the vehicle's braking performance, but the pedal gave a progressive response well up to the level required on my short trip. The exhaust brake on some of the longer downhill sections checked the vehicle's speed usefully. The legallyrated load for the front axle is six tonnes and the steering was light without being over-sensitive.

The specification for the vehicle is similar, in many ways, to that of the heavy haulage tractive unit as supplied for UK use. It has a 6.6-tonne capacity front axle and a 13.2-tonne single-reduction drive axle with hub reduction ratio of 2 to 1. The engine is the same 12-litre (732cuin) six-cylinder unit, but highly turbocharged, probably near to its limit, to produce the extra 19 kW (26 bhp).

As with all other major components, the SR62 eight-speed fully synchromesh rangechange gearbox and splitter giving 16 forward gears, is produced by Volvo.

The cab, apart from being left-hand drive, is identical to the UK model. Being fully sprung it tends to accentuate the angle of chassis roll. This, however, was not noticably worse than I had previously experienced in the F10, which had a lower c of g.

Tracking, I thought, might have been a problem, but the tri-axle trailer, with its self tracking rearmost axle, followed as well as any semi-trailer com bination I have driven — tyre scrub was little different than for a twin-axle bogie.

These outfits run at 15.5m but the extra three per cent in length went undetected from the driving seat, nor was it easily noticed from the rod side. Only the tanker-bodied vehicles, t;wilt to the greater capacity, looked in any sense bigger than the vehicles running on our own roads in the UK.. . .

From the driving point of view, I can't justify any cause for concern if heavier overall weights are introduced. As with the tractive units, the trailers will also have to be built to support the greater payload weight, in particular allowing for point loading. I noticed that while Egido was driving, he took extra care at raised level crossings and on rough road sections, as his own trailer had been con structed to accommodate an evenly distributed load.

Italy is subject to the same EEC rules as the UK and, like us, Italians have their own internal regulations. But I have the strong impression that it's not what the rules say that matters but the way they are interpreted and the extent to which they are enforced. The regulation 44tome maximum vehicle weight, almost 12 tons more than permitted in the UK, is blatantly ignored.

The speed limit is only 60km/ h but there is little enforcement of it. Tachographs are mandatory and are in fact fitted, so that a driver can be restricted to eight hours. When one disc overuns it can, and often is, changed. There are infrequent checks, but fines are small and financial benefits to driver and operator far outweigh any small losses.

General haulage operators' licences have been a problem ,for, until this year, the Italian Transport Minister had not issued any for 15 years. In typical Italian style, many operators have found a solution. It seems that licences have been available for specific types of haulage which employ vehicles with special body types such as tankers, pipe carriers etc.

Once armed with the relevant paperwork, the operator simply dismantles the superstructures so that the vehicle can be used on general haulage. To legalise the situation, the Transport Ministry issued 30,000 general haulage licences to these operators, but others who had kept within the boundaries of the law were ignored.

About 150,000 of the 1,110,000 or so vehicles operating in Italy are used on general haulage. Almost 45 per cent of this total are over 15 years old. The use of such a large percentage of old vehicles has done little to relieve the recession which they too have shared with the rest of the world in recent years.

Two years ago the introduction of the 8bhp/ tonne power requirement for vehicles running at 44 tons gave rise to a demand for more powerful tractive units of at least 352bhp. Bigger payloads and an increase in container traffic between the heavily industrialised northern area and its ports to the more central areas of Europe, has added to the articulated vehicle's pO pularity.

Fiat, the country's largest vehicle manufacturer, would seem to have been unprepared for the demand and, to some extent, has lost out with its large uncharged engine to foreign manufacturers' smaller, highly turbocharged units.

Earthmoving equipment company, Volvo BM, was quick to set up a commercial vehicle division to handle the import and sales for the Volvo F12., Now with 36 dealer service outlets, it has secured a five per cent share of the over-16-ton market with the variants of the one model: 74 per cent 4 x 2 tractive units, the rest 4 x 2 and 6 X 2 rigid units.

At the Volvo BM head

quarters in Zingonia, I talked with managing director Hans R. Feser. who explained other factors which have had to be taken into account for operating at maximum weight in addition to the extra power requirement.

Each axle 2m or more apart may have an imposed load of 12 tonnes; if less, the two axles must share a total imposed load not more than 18 tonnes. A further complication arises out of a condition which is the nearest thing to our own traction requirement. This states that the imposed load on the trailer axles must not exceed 1.4 times the weight of the fully laden tractive unit.

Two different five-axle combinations are possible — 6x 2 tractive unit, at 24 tonnes gross plus two-axle semi-trailer also 24 tonnes also provides ample latitude for operation at 44 tonnes gross. Alternatively a 4 x 2 tractive unit with maximum gross weight used in combination with tri-axle trailer falls Just short of 43.2 tonnes. The latter, with a self-steering rearmost axle on the semi-trailer is preferred by the majority of operators.

The F12 tractive unit is offered only as a 4 X 2. Far more important than the maximum permitted weight, I was told, is the overload factor, which in this instance is 30 per cent more than the legal limit of 56 tonnes gross, Although made in Belgium within the EEC, the F12 must also comply with the Italian type approval legislation. Air tanks, windscreen, spare wheel and exhaust are a few items which get special attention.

An appointment with a large operator was thwarted by a drivers strike. Gigi Lubrina assisted once again by arranging a visit to a family transport business, Auto Transporti Zanardi, operating 36 maximum-weight vehicles mainly north of Florence, but with some international running.

The purchase of four Fl 2s recently caused some comment locally, as the family is related to the Fiat dealer for the area. Through an interpreter, the point was made that they felt that the big Fiat engine was being developed at the expehse of the operator. Since its introduction, several changes have been made.

In answer to my question -Why choose Volvo?" I was told "My F12 has done 60,000 miles in six months but my older vehicles do an annual mileage of 75,000. The drivers want comfort. They like the speed and I like the fuel consumption of

around 41 lit/100km (6.9mpg).

At about 435,000 miles, the company sells its vehicles to owner-drivers who in return then contract for them. Each of the vehicles is equipped with radio-telephone to enable the drivers to receive and transmit information regarding loads. Local broadcasting regulations restrict the transmitters range to 25 miles but a repeater signal located in the mountains allows communication over most of northern Italy.

The Italian way is not ours but it does seem to work well.