We

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

mer's ride...

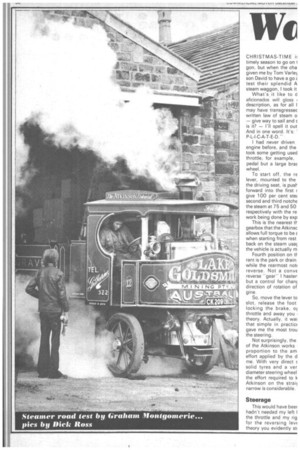

CHRISTMAS-TIME timely season to go on gon, but when the cha given me by Tom Varle son David to have a go e test their splendid A steam waggon, I took it

What's_ it like to d aficionados will gloss I description, as for all I may have transgressec written law of steam o — give way to sail and E is it? — I'll spell it out And in one word. It's: ' P-L-I-C-A-T-E-D."

I had never driven engine before, and the took some getting used throttle, for example, pedal but a large braE wheel.

To start off, the re lever, mounted to the the driving seat, is puslforward into the first I give 100 per cent steE second and third notche the steam at 75 and 50 respectively with the re work being done by exp

This is the nearest th gearbox that the Atkinsc allows full torque to be e when starting from rest back on the steam usaf the vehicle is actually m

Fourth position on tlrant is the park or drain while the rearmost not reverse. Not a convE reverse -gear" I haster but a control for chant direction of rotation of gine.

So, move the lever to slot, release the foot locking the brake, °I throttle and away you theory. Actually, it wa that simple in practicE gave me the most trou the steering.

Not surprisingly, the of the Atkinson works proportion to the am effort applied by the d me. With very direct E solid tyres and a ver diameter steering wheel the effort required to k Atkinson on the straii narrow is considerable.

Steerage

This would have beer hadn't needed my left I the throttle and my rig for the reversing lev( theory you evidently sti

-ler two hands.

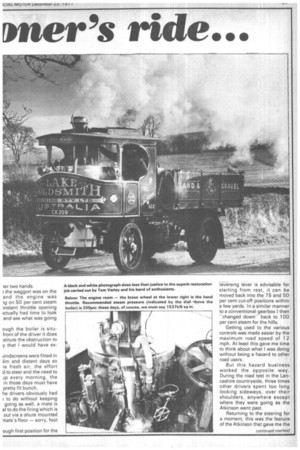

the waggon was on the and the engine was on 50 per cent steam yistant throttle opening ictually had time to look and see what was going ough the boiler is situfront of the driver it does stitute the obstruction to y that I would have ex

vindscreens were fitted in lim and distant days so le fresh air, the effort d to steer and the need to J p every morning, the in those days must have pretty fit bunch.

he drivers obviously had to do without keeping going as well, a mate is al to do the firing which is out via a shute mounted mate's floor — sorry, foot ough first position for the

–reversing lever is advisable for starting from rest, it can be moved back into the 75 and 50 per cent cut-off positions within a few yards. In a similar manner to a conventional gearbox I then "changed down" back to 100 per cent steam for the hills.

Getting used to the various controls was made easier by the maximum road speed of 12 mph. At least this gave me time to think about what I was doing without being a hazard to other road users.

But this hazard business worked the opposite way. During the road test in the Lancashire countryside, three times other drivers spent too long looking sideways, over their shoulders, anywhere except where they were going as the Atkinson went past.

Returning to the steering for a moment, this was the feature of the Atkinson that gave me the continued overleaf. most trouble. Now I have driven old commercial vehicles before — I have driven modern heavies without power steering before — and the Technical Editor could not be described as being a little lad—but I have to admit that I found it very hard work to get the steamer around corners.

Going up the hills around Gisburn was an interesting experience because of the totally different noise of a steam engine under load.

Here the technique was to go down to the first notch, open the hand throttle and the Atkinson would chug slowly up. With a top speed on the level of 12 mph, you would hardly expect the steamer to go charging up a 1 in 12 gradient at a high rate of knots, but the Atkinson always gave the impression that, however slowly it went up, it would get there in the end. Which is more than I can say for some of the modern equivalents!

Closing the throttle down would slow the Atkinson to a crawl which was rather more than the mechanical brakes could be guaranteed to do. The foot brake -took the form of a massive pedal rising out of the floor on the driver's side which expanded the shoes directly on to the wheel rim itself.

. .

Mate's job

The drum, which can be seen in the middle of the rear axle, is the park brake. It's controlled by a wind-on handle in the cab operated by the mate (demarkation?). It is an interesting point that the park brake should have its own brake drum whereas the foot brake operates directly on the wheel.

The suspension design is quite sophisticated even when compared with those of modern commercial vehicles. Using semi-elliptics front and rear, the Atkinson designers mounted the front springs rigidly at the forward end with slipper ends at the rear. At the rear, the springs are double-ended slippers with the location being taken care of by radius rods.

In the unladen condition, the .springs did not give an inch, but in spite of this and the solid tyres the ride was not quite as bonejarring as I had expected — or perhaps I was just too busy to notice.

I enjoyed driving the Atkinson very much indeed. At least the test will make me appreciate how hard the crew is working when a Sentinel eight-legger whistles past me on the next Historic Commercial Vehicle run.

If steam engines had not died out it would be interesting to speculate on what a 1978 40tonne (?) steam-powered tractive unit would look like.

One final thought. The advertising of the era in The Commercial Motor (on December 13th, 1921 to be exact) stated that the Atkinson Uniflow steamer was unrivalled for municipal purposes with one particular advantage being "ease of control or traffic." Were the drivers so much stronger or am I just getting old?

Could be.— Ed, • Graham Montgomerie.