The Results Obtained from a Comparative Road Test Prove the Striking Advantages of the Millam Free Wheel and Sprag

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

O GEAR130% FOR several years the MRlam free wheel • and sprag has been on the market for the private car, and from time to time we have referred to its development for commercial vehicles. The design is that of Frictionless Mastagear, Ltd., 1,251, Scotswood R o a d, South 13011We11, Newcastle; the company is, of course, associated with Sir W. G. Armstrong Whitworth and Co. (Engineers), Ltd. We have been privileged to follow the stages of development of this interesting gear, and the amount of trouble expended in testing out the design in every direction is a credit tothethoroughness of the concerns in question. Some criticism has been levelled at the principle of the free wheel. Therefore we suggested to the maker

of the a method of comparative testing, with which the company concurred, and recently it handed

over to us a sixwheeled Karrier bus equipped with the latest type of Mille in, incorporating a free wheel, automatic sprag and a double-faced cone clutch, which, while travelling, can be brought into operation to start the engine should it have stopped from any cause. It is possible to bring into action the engine, as a brake, whenever required and in any circumstances, whether freewheeling or not. The fear of being faced by a " dead " engine and a rotating propeller shaft is thus overcome..

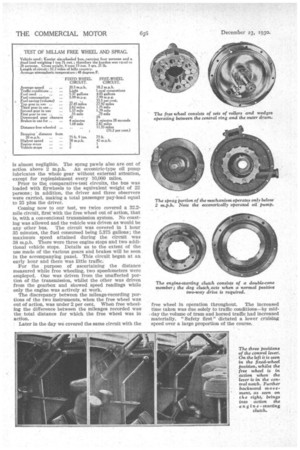

general layout of the gear is well displayed in the illustrations in struction and find_ that, although the complete gear weighs only about 11. cwt., the parts are extremely robust and the pressure upon the wedges when freewheeling is only about 1 lb. per sq. in, so that wear n25 is almost negligible. The sprag pawls also are out of action above 2 m.p.h. An eccentric-type oil pump lubricates the whole gear without external attention, except for replenishment every 10,000 miles.

Prior to thq comparative-test circuits, the bus was loaded with flywheels to the equivalent weight of 22 persons ; in addition, the driver and three observers were carried, making a total passenger pay-load equal to 25 plus the driver.

Coming now to our test, we twice covered a 32.2mile circuit, firsewith the free wheel out of action, that is, with a conventional transmission system. No coasting was allowed and the vehicle was driven as would be any other bus. The circuit was covered in 1 hour 35 minutes, the fuel consumed being 5.375 gallons ; the maximum speed attained during the circuit was 38 m.p.h. There were three engine stops and two additional vehicle stops. Details as to the extent of the use made of the various gears and brakes will be seen in the accompanying panel. This circuit began at an early hour and there was little traffic.

For the purpose of ascertaining the distance measured while free wheeling, two speedometers were employed. One was driven from the unaffected portion of the transmission, whilst the other was driven from the gearbox and showed speed readings while only the engine was actively at work.

The discrepancy between the mileage-recording portions of the two instruments, when the free wheel was out of action, was under 2 per cent. When free wheeling the difference between the mileages recorded was the total distance for which the free wheel was in action.

Later in the day we covered the same circuit with the

free wheel in operation throughout. The increased time taken was due solely to traffic conditions—by midday the volume of tram and horsed traffic had increased

• materially. "Safety first" dictated a lower cruising speed over a large proportion of the course. It will be seen from the matter embodied in the panel that the fuel consumption was at the rate of 7.99 m.p.g., an improvement of just 2 m.p.g., whilst the distance free wheeled was no less than 11.35 miles, or 35.2 per cent. of the distance run.

The figures contained in the panel speak for themselves in no uncertain manner, but it is interesting to analyse the re.sults. The saving in fuel (by volume), is 33.3 per cent., taking 5.99 m.p.g. as the basis. • The use of the free wheel reduced the number of gear changes by 28 per cent., whilst the .indirect gears were in use for .47 mile More when the free wheel was out of action.

When freewheeling the brake applications increased in number by 72 per cent., whilst the brakes were in use for 67 per cent, greater distance. From the point of view of braking efficiency the free wheel decreased the distance required to stop by .03 per cent.

So much for the results disclosed by our trial, as shown by facts and figures obtained over the chosen hilly route, which was as follows :—From Scotswood Works through Newburn, Throckley, Heddon-on-theWall, Corbridge, Stagshaw Bank, and on to the Roman Road back to Scotswood Works.

After the comparative tests were completed our representative took over the bus and drove it both with and without the free wheel in action. The gear change, although not a difficult one in the ordinary way, was absolutely foolproof when freewheeling; the ability to move the gear lever from top-gear position to that of first gear, or any other forward gear, coupled with the possible use of the free-wheel control at any time, confers the ability to use the engine as a brake, if desired.

The absence of any transmission harshness when changing gear, even without the use of the clutch, promises long transmission life—a badly needed feature for commercial-vehicle work to-day. The engine-starting clutch was tried out many times and worked very effectively. The " dead-engine " bogy, so much stressed by -critics of free wheels, has been overcome.

During the free-wheel circuit and subsequent to the comparative tests the sprag was tested. If desired, the vehicle can be allowed to come to rest without the use of either brake, so long as the machine is on the up grade. When forward motion ceases, the sprag holds the wheels instantly and entirely automatically. Above 2 m.p.h. the sprag was entirely out of action, so that there was no noise from it and no wear of the pawls or ratchet. Below 2 m.p.h. the sprag was not heard ; it is immersed in an oil-bath.

The Millam engineers have thought of all contingencies from the point of view of the commercialvehicle operator, and it is interesting to learn that manufacturers bn the Continent, in America and, of course, in this country, are showing a practical interest in the device. That it is an efficient piece of mechanism, capable of effecting savings with regard to both operating costs and maintenance expenses, there is no doubt, as revealed by the figures put forward in this article. The absence of oil pumping, in the cylinders, when the engine is not pulling alone spells reduced "top overhaul" workand cuts down oil consumption.