Significance of Depreciation in Luxury Coaches

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN "The Commercial Motor," dated March 12, I dealt with the case of an operator who was buying £40,000 worth of motor coaches in 1948 and was perturbed by the fact that he would not receive the benefit of the initial and wear-and-tear allowances amounting to €18,000 on which he cou;d claim rebate of income tax, until 1950.

Closing the article I drew a parallel between hiscase arid that of the little man spending about £4,000 on one coach who would have to wait a corresponding period for his £1,800 allowance, I said that this delayed action might have a useful effect because in that way he would not be so likely to over-estimate his profits and under-estimate his charges, as if he received the benefit of that rebate immediately.

Misled by Rebate

In the event of his receiving that rebate immediately he would appear to be .£800 better off in that first year so that quite moderate fares would show an apparent profit: the awakening would come in subsequent years when he would not receive that seeming gratuity from the Inland Revenue.

I pointed out further that even so large a corporation as The Northern Ireland Road Transport Board was spreading -ever five years the relief afforded by the initial capital expenditure allowance of 20 per cent. .

-1 Might also have referred to a point raised during an .inquiry into a plea for operators in the metropolitan, eastern and south-eastern licensing areas for a general rise in coach .fares: That was denied them and in the course of the hearing the authorities made it clear that they regarded a 25 "per.cent. allowance on diminishing values as reasonable. They pointed out that if an operator accepts delivery of a large number of new vehicles in one financial year at the present enhanced prices a fairer picture of the general position would probably he provided if the increased allowance for depreciation were spread over a number of years instead of falling with devastating effect on the accounts for one financial year.

At the inquiry one London operator said that a sudden increase in the allowance for depreciation might convert an operating profit of 0.5d. per mile in 1947 into a loss of 0.8d. per mile in 1948.

As a matter of fact I would go further and recommend that the amounts set aside for depreciation should be the same each year, say 20 or 25 per gent. per annum of the original value of the vehicle. Only in that way can a stabilized rates-schedule, based on cost plus profit. be achieved. I now propose to implement .the promise made in that article to discuss this more practical aspect of depreciation in relation to luxury coaches I am reminded in this connection of a comment made . by a friend of mine, secretary to a local cricket club, who found that he had in 1947 to pay -twice as much for the hire of a coach for his cricket tour than he had done in 1939. Prior to the tour I had satisfied him.that there was justification for this seemingly extravagant rise in prices. He was, however, considerably perturbed to find that not only was the driver the one wha had driven them in 1939 but the coach itself -was-the same.

He happened to be an accountant and he immediately charged me with bias in favour-of the operator as, he said, surely this coach which was, not new.eight years ago must stand in the operator's books at a very low figure in-1947 and in his view that item ought to be set off against some of the increases in eosts which! had put forward in justification of the enhanced price he had to pay for the tour. My answer was a question From where did he expect the operator to get a new coach ;lid how much did he think he would have to pay for it?

Inflated Prices

That did not interest him at all until I explained that in assessing costs as a basis for rates and charges the item depreciation was looked upon not as a measure of the book value of the vehicle, hut as provision for the purchase of a new one and that the operator, when he replaced the coach, would have to pay at least two-arid-a-half times as much for the new one.

His item depreciation Was to be computed in relation to the price of the new vehicle, that is if he was to be able to provide for fleet renewals at present-day prices.

I have in mind coaches to he used for luxury tours and excursions and for private parties of a kind in which the rider is willing to pay whatever is asked but does expect the best in the way of comfort and appearance. It is important to emphasize that because I am not in this article dealing with coaches for everyday work such as industrial transport.

In my view coach operators may expect in the near future to meet competition as keen as any in pre-war days. This competition may be of a different nature but the result will be the same.

An ominous pointer comes from the recent developments in connection with railway travel. The British Railways, Government backed, are likely to prove no mean opponent. They have already started to fight. The renewal of schemes for excursions, cheap-day tickets and the like, is only a preliminary. More developments of a similar nature are sure to come as the year grows older.

Those who are inclined to take advantage of these railway . facilities may not seem to be the sort of people who would use luxury coaches. It might seem that that sort of competition is not of any significance. Perhaps it is not directly, but it will affect the market indirectly because the more people who are persuaded to go by train, the less there a31 will be to use the coach services and the fewer the passengers the more " ehoosy " they are likely to be. In those circumstances undoubtedly the best appointed coaches will get the business.

Such conditions will bring oncemore into the picture the heavy depreciation factor which was so controversial a subject in pre-war days.

Taking tours and excursions first, and especially holiday cruises and tours, prices are more or less fixed; operators can therefore compete only in the service they-render., A considerable factor in that service will be the comfort and luxury of the vehicles. In other words, new and expensive coaches are going to be essential to success.

False Popularity Operators should not be deluded by the rush in big cities to book seats on coaches, so widely publicized In my view that was largely the outcome of panic and as is usual in such cases may bring about a reaction which will be a reversal of the tendency to -travel by coach. Indeed, the fact that so much publicity, has been given to the matter has already given rise in the minds of many thousands to the idea that it might be as well to go by rail after all. In coaching. as in many other industries, the sellers' market is passing. Coach operators will have to offer something out of the way and special if they are to keep their vehicles fully occupied in the near future. In considering the depreciation of buses or lorries, mileage counts. It may be calculated on a basis of 240,000 to 300.000 miles in tbc life of a first-class vehicle or 90.000 to 100.000 in a low-priced machine. The expectation of life does not matter. It is the principle with which we are concerned

In the case of such vehicles obsolescence does enter into the matter but only to a small degree, determined partly by the class of business and partly by the extent to which a vehicle, perhaps too old for one service, can be turned over to another controlled by the same operator but where age is not of such consequence. Obsolescence prevails in every instance of commercial vehicle use, but in the case of the luxury coach it is obsolescence which predominates, and not wear and tear. A coach is out of date and unsuitable for its purpose long before a is won, out.

Obsolescence a Big Item In the case of a luxury coach, obsolescence can be a very serious factor. New coaches to-day embody in their chassis construction, as well as in the make-up and decoration of the body, developments which have come about during or just after. the war. Better engine suspension, improved transmission, braking and suspension, all make for more comfortable riding. The use of light metals. better upholstery. new kinds of panelling, walls and ceiling, all contribute to that indefinable quality which we call luxury.

The life of a luxury coach, as such, it seems, is approximately two years. After that it becomes second-grade and useful only for those services the users of which are not so particular—parties to football matches, theatres, dog races and so on. The large operator, operating luxury tours, private hire, ordinary tours and excursions as well as public service vehicles and services for workmen, can meet these circumstances quite comfortably by handing down vehicles from one stage to another until by the time they reach the last one they are worn out as well as obsolete. For the small man this process of handing down is not practicable within the bounds of his own organization. That indeed is one reason why the small man finds it difficult to

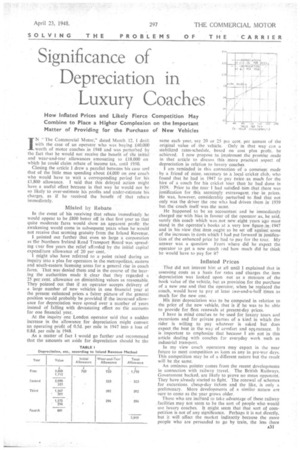

make a reasonable profit out of charges which have been fixed to meet the conditions •uoder. which large operators work. Take the case of an operator with five vehicleas of which four are in regular use and the fifth is a stand-by for hiring or is a substitute vehicle in case of breakdown. Of the four, two are, shallwe say, reserved for luxury tours arid two for -what I call second-grade work. How is depreciation to be assessed in such a case? • Assume the initial.cost of the vehicle to be £3,800 and take £100, a round figure, for cost_of tyres. • The net value of the vehicle for assessment of depreciation is-thus £3,700 An operator carrying . on under the conditions just indicated is obviously working on a four-year eyele. Each bus serves two years as a luxury coach. two Years as secondgrade and then apart from the One which serves another two years as a stand-by, must be put away. ,

The first thing we should know is. what he is likely to get for his luxury vehicles four years from now.

The operator might suggest £700; on the other hand he might be optimistic and take £1,000. I will take the optimistic ficure and deducting that from £3,700' we get £2,700 as the actual basic figure for. assessment of depreciation. That has to be written off in four years and is therefore equivalent to £675 per annum, or £13 10s per week of a 50-week year. Alternatively if the vehicle runs 100,000 miles in the time, the depreciation is 64d. per mile.

No "Class" Distinction. Theie is no point, in my view, in attempting to differentiate between the depreciation allowed for the period during which the vehicle is a luxury, coach and that during which it is engaged on what I have called second-grade . work. For one thing it may reasonably be expected that the maintenance cost will be at minimum during the first two years and will be much more during the second two years so that the difference in total cost arrived at. by decreasing depreciation in the first two years is offset because of the saving in maintenance, It is much better to take an average figure throughout the whole of the period involved, for maintenance as well as depreciation.

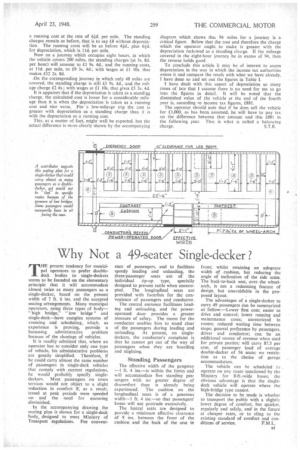

Moreover, we are not concerned with making a difference in rate between employment as luxury coaches and for second-grade work. In most cases that cannot be done anyway. The luxury coach is there to ensure, by the attraction of its greater comfort and better equipment, that every seat is filled on every journey against whatever competition there may be. It may be interesting to decide whether it is preferable to reckon the depreciation on a time basis at £13 10s. per week or on a mileage basis of 6,41. per mile.

Take the time basis first. The other standing charges will be: tax, £1 5s.; rent, 10se. insurance, £1 5s.; interest, £2; overheads or administrative charges, £3; that is a total of £8 per week, so that with depreciation-at £13 10s. the standing charges amount to £21 10s. per week and on a 44-hour week that is 10s. per hour as near as makes no matter. For running costs, taking an oil-engined vehicle, the approximate figures are: fuel and lubricants, lid. per mile; tyres, Iid.; maintenance, lid.; total 40. per mile.

Now on an eight-hour journey in which-the vehicle covers 200 miles, the cost will comprise eight hours at 10s., £4, 200 miles at 40., £3 15s.. plus £1 10s, for wages, the total being £9 5s, On a job which still takes eight hours, in which the vehicle covers only 48 miles, the cost. similarly assessed, will be 16 8s. I must stress that these figures relate to cost only and not to charges. Now assume that the depreciation is to be estimated as

a running cost at the rate of 60. per mile. The standing charges remain as before, that is to say £8 without depreciation. The running costs will be as before 40., plus 80. for depreciation, which is lid, per mile.

Now on a journey which occupies eight hours, in which the vehicle covers 200 miles, the standing charges (at 3s. 8d. per hour) will amount to £1 9s. 44., and the running costs, at lid, per mile, to £9 3s. 4d.; with Wages at £1 10s. that makes £12 2s. 8d.

An the corresponding journey in which only 48 miles are covered, the standing charge is still £1 9s. 4d., and the milage charge £2 4s.; with wages at £1 10s, that gives £5 3s. 4d.

It is apparent that if the depreciation is taken as a stand* charge, the calculated cost is lower for a considerable mileage than it is when the depreciation is taken as a running cost and vice versa. For a low-mileage trip the cost is greater with depreciation as a standing charge than it is with the depreciation as a running cost.

This, as a matter of fact, might well be expected, but the actual difference is more clearly shown by the accompanying

diagram which shows thaL 94 miles for a journey is a critical figure. Below that the cost and therefore the charge which the operator ought, to make is greater with the depreciation reckoned as a standing charge. If the mileage covered in the eight-hour journey be in excess of 94, then the reverse holds good.

To conclude this article it may be of interest to assess depreciation in the way in which the income tax authorities assess it and compare the result with what we have already. I have done so and set out the figures in Table I.

I have dealt with this aspect of depreciation so many times of late that I assume there is no need for me to go into the figures in detail. It will be noted that the diminished value of the vehicle at the end of the fourth year is, according to income tax figures, £881.

The operator should note that if he does sell the vehicle for £1,000, as has been assumed, he will have to pay tax on the difference between that amount and this £881 in the following year. That is what is called a balancing charge. S.T.R.