ationary vehicles, 1: tiding and unloading

Page 63

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

3.2 of Part A of the Royal Society of Arts syllabus for :ertificate of Professional Competence deals with par, waiting, loading and unloading, all subjects of considle interest to both goods and public service vehicle ate rs.

ie ceneral law on stationary vehicles is contained in Regulation of Motor Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations which reads: No person in charge of a motor vehicle or r shall cause or permit the motor vehicle or trailer to stand on a so as to cause unnecessary obstruction thereof."

us regulation applies to every road whether it is a quiet e-sac, a busy city street or an important trunk road. There is no for signs prohibiting or limiting waiting or for any special order in force for this regulation to be effective. All that is necessary r the prosecution to be able to prove that an obstruction was ed.

Solomon v Durbridge (1956) 120 JP 231, it was held that a cle could become an unnecessary obstruction if it was left on a for too long a period. In this case the defendant left his car ter ded on the Victoria Embankment, London, from 1 1am until 5pm. He was convicted of causing unnecessary obstruction and ppealed. Dismissing the appeal, it was held that the offence was ausing obstruction, but causing unnecessary obstruction and leaving a car in this way for that length of time was unnecessary ruction.

he opposite view was taken in Police v O'Conner (1957) CLR where an artic was parked outside the driver's house in a ie-sac from 7.30pm to 9pm. The driver was charged under ula..ion 114 and was convicted. In allowing his appeal, it was that there was no evidence before the court to show unreaable use of the road and that the mere presence of a motor cle on the highway is no evidence of unreasonable use.

will be seen that in this case the period for which the vehicle pa -ked was very much less than in the previous case and the lily was very different.

1 Ellis v Smith (1962) 3 All E.R. 954, a bus stood at a bus stop er ough to cause an unnecessary obstruction because a relief ar was late in arriving. It was held that the driver who was going luty was in charge of the bus until he handed it over to his relief therefore he, though not necessarily he alone, committed the nce.

There a taxi, attempting a U-turn in Oxford Street, London, ight traffic to a halt for nearly a minute, it was held that there evidence upon which obstruction could be found as a fact and conviction stood, despite the driver's plea that his conduct had been unreasonable (Wall v Williams (1966) Crim L.R. 50).

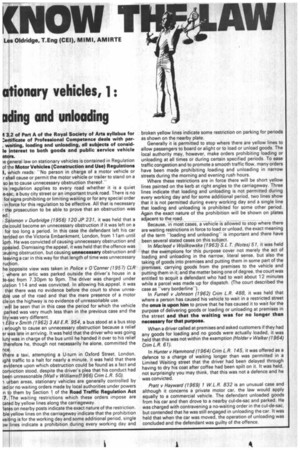

urban areas, stationary vehicles are generally controlled by ted or no waiting orders made by local authorities under powers ,n to them by Section 1 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 7. The waiting restrictions which these orders impose are z.tated by yellow lines along the carriageway.

lates on nearby posts indicate the exact nature of the restriction. ble yellow lines on the carriageway indicate that the prohibition vaiting is for the working day and some additional period, single )yv lines indicate a prohibition during every working day and broken yellow lines indicate some restriction on parking for periods as shown on the nearby plate.

Generally it is permitted to stop where there are yellow lines to allow passengers to board or alight or to load or unload goods. The local authority may, however, make orders prohibiting loading or unloading at all times or during certain specified periods. To ease traffic congestion and to promote a smooth traffic flow, many orders have been made prohibiting loading and unloading in narrow streets during the morning and evening rush hours.

Where these restrictions are in force there will be short yellow lines painted on the kerb at right angles to the carriageway. Three lines indicate that loading and unloading is not permitted during every working day and for some additional period, two lines show that it is not permitted during every working day and a single line that loading and unloading is prohibited for some other period. Again the exact nature of the prohibition will be shown on plates adjacent to the road.

Because, in most cases, a vehicle is allowed to stop where there are waiting restrictions in force to load or unload, the exact meaning of the term "loading and unloadingis important and there have been several stated cases on this subject.

In Macleod v Woilkowska (1963) S.L.T. (Notes) 51, it was held that the exemptions for this purpose cover not merely the act of loading and unloading in the narrow, literal sense, but also the taking of goods into premises and putting them in some part of the premises, carrying goods from the premises to the vehicle and putting them in it; and the matter being one of degree, the court was entitled to acquit a defendant who had to wait about 12 minutes while a parcel was made up for dispatch. (The court described the case as "very borderline").

In Purnell v Johnson (1962) Crim L.R. 488, it was held that where a person has caused his vehicle to wait in a restricted street the onus is upon him to prove that he has caused it to wait for the purpose of delivering goods or loading or unloading at premises in the street and that the waiting was for no longer than necessary for that purpose.

When a driver called at premises and asked customers if they had any goods for loading and no goods were actually loaded, it was held that this was not within the exemption (Holder v Walker (1964) Crim L.R. 61).

In Hunter v Hammond (1964) Crim L.R. 145, it was offered as a defence to a charge of waiting longer than was permitted in a Limited Waiting street that the driver had been delayed through having to dry his coat after coffee had been spilt on it. It was held, not surprisingly you may think, that this was not a defence and he was convicted.

Pratt v Hayward (1969) 1 W.L.R. 832 is an unusual case and although it concerns a private motor car, the law would apply equally to a commercial vehicle. The defendant unloaded goods from his car and then drove to a nearby cul-de-sac and parked. He was charged with contravening a no-waiting order in the cul-de-sac, but contended that he was still engaged in unloading the car. It was held that when the car was moved, the operation of unloading was concluded and the defendant was guilty of the offence.